School districts in California receive funding to educate each student in their care.

In This Lesson

How did education funding work before LCFF?

What is the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF)?

Is LCFF good policy?

How is LCFF funding calculated?

Which student characteristics count in LCFF?

What is the LCFF concentration factor?

What is LCFF supplemental funding?

What is the LCFF equity multiplier?

Is LCFF fair? Is it equitable?

Are LCFF funds restricted?

Are LCFF funds used as intended?

Are Special Education funds part of LCFF?

Which education funds are not part of LCFF in California?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

The amount they receive from the state varies depending on the characteristics of students. This system is known as the Local Control Funding Formula, or LCFF.

To understand any system, it helps to follow the money. This lesson explains how LCFF works, how it came to be, why it's important, why it is generally admired as good policy, and why informed community members have become so essential to it.

What is LCFF?

California's Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) allocates state funds to school districts based on the characteristics of students attending school in them, providing more money to districts where student needs are greater. These funds are substantially unrestricted. The big idea of LCFF is that school districts are equipped with money and power to serve the needs of the students they are educating. Districts that have many "higher need" students get more money from the state budget to serve those students. Here is how it works:

- Base Funding: All districts receive a base grant for each student who comes to school. The base grant is larger for grades 9-12 than for other grade levels.

- Supplemental Funding: Districts receive 20% additional funding per student for students with high needs — specifically defined as learning English, in poverty, homeless, or in foster care.

- Concentration Funding: Districts are provided additional money if more than 55% of children in the district qualify as having high needs. Specifically, the district receives an extra 65% of the base grant for each high-need student beyond the 55% threshold. For example, a district where 60% of the students are in a high-need category receives 165% of the base for 5% of its students.

- Equity multiplier: Beginning in 2023-24, the state added the option of providing additional funding in support of high-need school sites where more than 70% of the student population is socioeconomically disadvantaged. Total funding for this program is specified in the state budget each year.

The end result under the LCFF system is that districts where students have higher needs receive more money to address those needs.

Local control vs. state control

The LCFF system gives school districts a lot of local power. It was not always so.

The golden rule: “Whoever has the gold makes the rules.”

From 1978 through 2013, California's education finance system was very centralized, complicated, and unfair. Laws and policies set in Sacramento determined the amount of money each school district received. Significant portions of the money were earmarked for specific categorical purposes, almost like coupons. To prove their compliance with the terms of each categorical program, districts filed bushels of reports. In effect, California had a statewide system of state schools.

In 2013, as this lesson will explain, the California legislature dramatically decentralized the school finance system, aiming to create a statewide system of local school districts. The Local Control Funding Formula eliminated virtually all categorical programs. School districts were given far more power to make choices locally about how to put money to use.

Today, school districts have considerable control over money and how to spend it. (In Educationese, the state apportions funds to Local Education Agencies, a term that includes school districts, county offices of education and charter schools. Insiders call them LEAs, pronounced as the letters, not like the name of a certain Jedi princess.)

Under LCFF, the use of funds is substantially unrestricted, which means that school districts have a lot of latitude, so long as they spend the supplemental and concentration funds in ways that follow the intent of the law. This was a big change. Now it is school districts that hold the gold, and make the rules.

Unrestricted: Now it is school districts that hold the gold and make the rules.

LCFF accountability: the LCAP

In principle, school districts are accountable to their community for using LCFF funds as intended. Are districts actually following through on the intent of LCFF by investing more money in higher-need students?

It is up to each community to enforce the intent of LCFF.

Often not, unfortunately. But it's unfortunately hard to know.

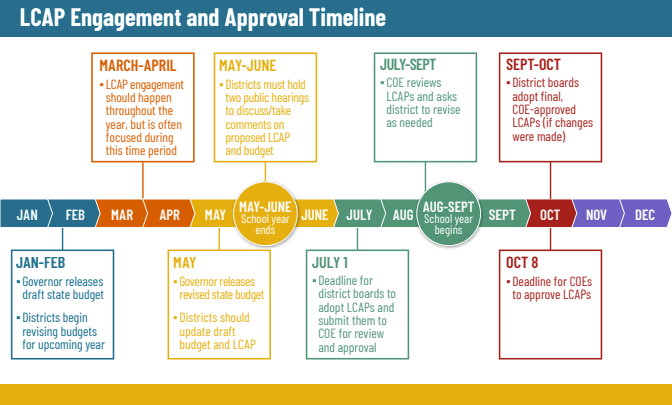

To provide transparency about the intended and actual use of LCFF funds, districts are required to prepare an annual Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP). Who enforces the use of funds under LCFF? In practice, you do. It is up to community members to stand up for the intent of the law.

A 2020 study of 14 districts by the Edunomics Lab found that only two of them spent money on high-need students in proportion to the additional money received.

In 2023, Public Advocates found that "most districts exclude significant programs and expenditures from their LCAPs, include only a fraction of their budgets, and fail to describe actions – including discretionary school site allocations – with enough detail for communities to understand what districts are doing or monitor whether programs and services are implemented and effective." Nonprofit law firms and advocacy groups like Public Advocates and ACLU have helped communities enforce the law when districts have used LCFF targeted funds in untargeted ways.

Standard public reports don't necessarily show where school district money is spent. In some cases, organizations have had to use Freedom of Information Act requests and the threat of litigation to obtain the detailed information required. It's a serious matter: in 2017 Los Angeles Unified settled such a case for $150 million.

In order to encourage local oversight, school districts are required to engage parents and communities in development of each LCAP. See Lesson 7.10 and the Ed100 LCAP Checklist for more information about how spending decisions are made.

The exceptions to LCFF

California accomplished the transition to the LCFF system with unexpected speed and unity. Originally forecast to take seven years, the job was essentially done in three due to strong growth in California's tax receipts.

At this point, the LCFF calculation determines the education funding for virtually all school districts. There are only a few exceptions, generally known as Basic Aid districts, where locally-generated taxes are greater than the level guaranteed by the state.

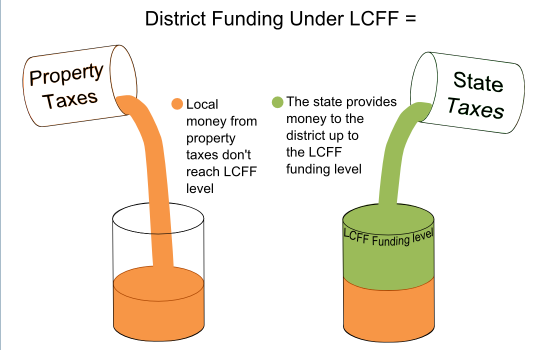

The first step in filling a district's LCFF bucket is to pour in all the local property taxes. If those taxes fill the bucket halfway, state money is used to fill the other half of the bucket. For example, if property taxes fill the bucket two-thirds of the way, state money fills the other third.

The first step in filling a district's LCFF bucket is to pour in all the local property taxes. If those taxes fill the bucket halfway, state money is used to fill the other half of the bucket. For example, if property taxes fill the bucket two-thirds of the way, state money fills the other third.

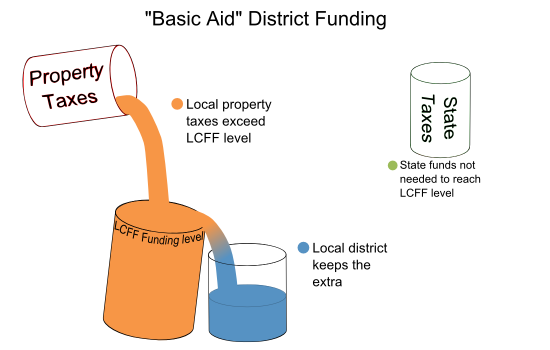

In rare school districts in California, local property taxes fill or overflow the LCFF Funding Bucket. In those cases, the districts keep their property taxes and get no LCFF money from the state. These are known as Basic Aid or Excess Tax districts.

In rare school districts in California, local property taxes fill or overflow the LCFF Funding Bucket. In those cases, the districts keep their property taxes and get no LCFF money from the state. These are known as Basic Aid or Excess Tax districts.

Some funds are outside of LCFF

LCFF did not eliminate all categorical funds, partly because some of them are designed to align with the requirements of federal programs. The largest of these programs is Special Education, which has its own set of allocation rules and also requires the district to spend funds from its base allocation. Ed100 Lesson 8.6 explains more about the exceptions to the LCFF funding system.

Is LCFF Working?

The short answer is yes. LCFF made California's education funding system dramatically better.

In 2005-2007 a set of 20 research studies collectively known as Getting Down to Facts set the stage for change and led to the adoption and implementation of LCFF. In 2018 a set of follow-up studies (the Getting Down to Facts II project (GDTFII) confirmed that “money targeted to districts with the greatest student needs… led to improvements in student outcomes.”

An associated study, Money and Freedom, found that additional funds apportioned through LCFF made a distinct, measurable difference:

“We find that LCFF-induced increases in school spending led to significant increases in high school graduation rates and academic achievement, particularly among poor and minority students. …In sum, the evidence suggests that money targeted to students' needs can make a significant difference in student outcomes and can narrow achievement gaps.”

In 2023, ten years after the implementation of LCFF, studies of the impact of the policy were even more conclusive:

“LCFF-induced funding increases significantly improved academic achievement for every grade and subject assessed, reduced grade repetition, enabled lower suspension rates, and increased the likelihood of students graduating from high school and being college-ready. The impact on student achievement grew with years of exposure to increased funding and with the amount of the funding increase. District investments in instructional inputs, including reduced class size, increased teacher salaries, and teacher retention, were associated with improved student outcomes.”

Of course, there is still plenty of room for improvement. Local accountability is great in theory, but implementation matters. The Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP) is a complex report. Understanding it and advocating for tradeoffs relies heavily on well-informed and deeply engaged community members. That's a tall order, as explained in Lesson 7.10.

For now let's stay with this chapter's theme, which is to explore where money for education in California comes from, where it goes and why. The next lesson, 8.6, examines the use of categorical funds, which districts may only spend in specific ways.

This lesson was updated in October, 2025.

Quiz×

CHAPTER 8:

…with Resources…

-

…with Resources…

Overview of Chapter 8 -

Education Spending

Does California Spend Enough on Education? -

Education Purchasing Power

What Can Education Dollars Buy? -

Who Pays for Schools?

Where California's Public School Funds Come From -

Prop 13 and Prop 98

Initiatives That Shaped California's Education System -

LCFF

The Formula That Controls Most School Funding -

Categorical Funds

Special Education and Other Exceptions -

School Funding

How Money Reaches the Classroom -

Do California Schools Waste Money?

Is Education Money Well Spent? -

More Money for Education

What Are the Options? -

Parcel Taxes

Only in California... -

School Volunteers

Stealth Wealth for Schools

Related

-

The Role of Parents

Education and Families -

Special Education

Why Not Teach All Kids Alike? -

Child Protection

Intervention and foster care -

Teacher Placement

Who Teaches Where? -

Class Size

How Big Should Classes Be? -

After School Learning

Extending the School Day -

Literacy in California

Ensuring All Kids Can Read, Write and Speak English -

Arts Education

Creativity in California Schools -

P.E. and School Sports

How Does Sweat and Movement Help Learning? -

Field Trips

Beyond the Classroom -

How do Kids Become Bilingual?

World Language Learning in California Schools -

Financial Literacy in California

Learning to Earn -

The Role of State Government in Education

California’s Constitutional Responsibility -

School Districts in California

What do School Districts Do? -

Accountability in Education

Who Monitors the Quality of Schools? -

The LCAP

Annual Plans for California School Districts -

Who Pays for Schools?

Where California's Public School Funds Come From -

Prop 13 and Prop 98

Initiatives That Shaped California's Education System -

Categorical Funds

Special Education and Other Exceptions -

Do California Schools Waste Money?

Is Education Money Well Spent? -

More Money for Education

What Are the Options? -

School Volunteers

Stealth Wealth for Schools -

Education Data in California

Keeping Track of the School System -

The California School Dashboard

Measuring California School Performance -

Change

What Causes Change in Education?

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Carol Kocivar February 10, 2026 at 2:03 pm

1. Future enrollment declines may offer the opportunity to modify the funding formula without reducing funding for any districts

2.Basing funds on student enrollment rather than attendance would benefit higher-need districts.

3.Regional cost adjustments would redirect funding from rural and high-need districts to urban and suburban areas.

4.Providing additional funding for students with overlapping needs would direct more resources to most high-need districts.

5. Changing how the formula addresses concentrated need could increase revenues for districts with moderate shares of high-need students.

https://www.ppic.org/publication/updating-californias-school-funding-formula-assessing-alternatives-and-trade-offs/

Carol Kocivar February 10, 2026 at 1:51 pm

This 2025 report from PACE is the first major study of basic aid since the enactment of LCFF in 2013. It finds that 139 districts serving just 5.5 percent of California’s TK–12 students are benefitting from growing funding advantages. Excess local revenue in basic aid districts has risen 41 percent (17 percent when adjusted for inflation) over 5 years—outpacing LCFF growth and widening the gap between property-rich districts and those that rely on state aid.

Teachers in those wealthy “basic aid districts” earn an average of $27,000 more than those in state-funded districts, according to the study.

A decline in enrollment lowers per-student funding under LCFF, but raises per-student funding in basic aid districts.

Carol Kocivar December 10, 2025 at 12:35 pm

https://www.ppic.org/ Public Policy Institute of California

This policy brief examines enrollment based funding, regional costs adjustments, duplicated funding for students with multiple needs, and gradual funding increases for concentrated needs.

We model the state’s funding system and consider several distinct formula changes, ranging in cost from $1.5 to $3.8 billion and each leading to different allocations across districts and student groups. Increased per student funding due to future enrollment declines may offer policymakers the opportunity to modify the LCFF without reducing funding for any districts.

Carol Kocivar April 24, 2025 at 3:35 pm

Want more detail about LCFF? This 2025 official brief for California's legislators explains deeply. It includes:

- Background on LCFF’s implementation,

- How the formula works for school districts and charter schools,

- How the formula was phased in, and

- Requirements for districts to adopt plans that describe how LCFF funding will be spent.

Carol Kocivar December 28, 2024 at 4:53 pm

"State policymakers–especially those serving on Education Committees–have an important role in understanding the importance of equitable school funding and shaping their state’s school finance strategies. This responsibility includes having an awareness of emerging topics in school funding, including declining student enrollment, instability in state budgets, the needs of different student populations, and the reduction of federal funds."

https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/event/webinar-emerging-topics-education-finance

Carol Kocivar December 28, 2024 at 4:42 pm

"First implemented over 10 years ago, California’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) provides California’s public schools with additional funding for high-need students. It uses enrollment in the Free and Reduced-Price Meal program (FRPM) to proxy for low-income status. Yet the gap between FRPM and other poverty measures has been growing over time.

"https://www.ppic.org/blog/video-funding-student-need/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=video-funding-student-need?utm_source=ppic&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=blog_subscriber

Peter McManus August 19, 2024 at 9:23 am

FillmoreSlim July 22, 2024 at 6:52 pm

" Under LCFF, the use of funds is substantially unrestricted, meaning that school districts have a lot of latitude, so long as they spend the supplemental and concentration funds in ways that follow the intent of the law."

BTW, I really enjoy this site! Thank you!

Jeff Camp - Founder July 29, 2024 at 9:57 am

Cary September 28, 2023 at 3:02 am

Carol Kocivar April 26, 2023 at 7:53 pm

This study by the Legislative Analyst provides some historical background on LCFF’s implementation, describes how the formula works for school districts and charter schools, describes how the formula was phased in, and explain requirements for districts to adopt plans that describe how LCFF funding will be spent.

https://abgt.assembly.ca.gov/sites/abgt.assembly.ca.gov/files/04.11%20Appendix%20B%20LAO%20LCFF.pdf

Carol Kocivar March 24, 2023 at 4:35 pm

California, reviews LCFF implementation to offer guidance on improving equitable outcomes and community engagement. While the report highlights some bright spots, it underscores the need for significant innovation in order to strengthen accountability measures that can ensure a comprehensive strategic planning process and better engagement.

https://publicadvocates.org/realizing-the-promise-of-lcff-recommendations-from-the-first-ten-years/

Carol Kocivar January 9, 2023 at 3:54 pm

The Local Control Funding Formula for School Districts and Charter Schools

https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Report/4661?utm_source=laowww&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=4661

Carol Kocivar August 4, 2022 at 2:30 pm

The Budget includes total funding of $128.6 billion for K-12 education:

All state and federal funds $22,893 per pupil

State only: Proposition 98 General Fund $16,993 K-12 per pupil

In addition to this funding, the Budget includes $5.1 billion General Fund for K-12 school facilities, including new preschool and transitional kindergarten facilities.

This Budget is $35.8 billion Proposition 98 funds above the 2021 K-14 education budget and contains more funding for community schools and universal high-quality school meals.

It also accelerates funding for extended learning opportunities that will provide families the opportunity for a 9-hour day filled with academics and enrichment, including six weeks during the summer.

Budget details by topic are now included in the comments at the end of the appropriate Ed100 lesson..

.

Carol Kocivar July 23, 2022 at 6:35 pm

Grade Span Amount per student

TK/K3 $10,082

4-6 $9,270

7-8 $9,544

9-12 $11,349

Supplemental Grant 20%

Districts receive 20% additional funding per student for students with higher needs

Concentration Grant 65%

New in 2022. Higher concentration grant funding.

If more than 55% of children in the district are in poverty, in foster care, or learning English, the district receives an extra 65 % (instead of the previous 50 %) of the base grant for each student beyond the 55% threshold.

Jeff Camp - Founder June 28, 2022 at 12:43 am

Carol Kocivar October 19, 2021 at 12:09 pm

To increase the number of adults providing direct services to students on school campuses, the 2021-22 Budget includes an ongoing increase to the LCFF concentration grant of $1.1 billion Proposition 98 General Fund, increasing the concentration grant from

50 to 65 percent of the LCFF base grant. Local educational agencies that are recipients of these funds will be required to demonstrate in their local control and accountability plans how these funds are used to increase the number of certificated and classified staff on their campuses, including school counselors, nurses, teachers, paraprofessionals, custodial staff, and other student support providers

Carol Kocivar October 8, 2021 at 4:21 pm

An Oct, 2021 report from the Public Policy Institute of Callifornia on LCFF funding shows positive results. These include:

1. Under LCFF, resources were distributed more equitably across districts.

2. Revenues and spending increased fastest in high-need districts.

3. Test scores and A–G completion increased most in the highest-need districts after the state fully implemented the funding formula.

Among the PPIC recommendations:

1. Improve reporting to enhance tracking and transparency of funding.

2. Consider a funding mechanism based on school site need

3. Increase supplemental grants and/or lowering the threshold for concentration grants.

Lots more data. Read the report.

https://www.ppic.org/publication/targeted-k-12-funding-and-student-outcomes/

francisco molina August 19, 2019 at 2:10 am

Caroline August 15, 2019 at 6:00 pm

Jeff Camp August 16, 2019 at 11:11 am

Jennifer B February 19, 2019 at 9:24 pm

Jennifer B February 20, 2019 at 8:10 am

Gloria Lucioni January 6, 2019 at 6:55 pm

francisco molina August 20, 2019 at 1:19 am

luciab September 24, 2018 at 2:24 pm

Jeff Camp October 1, 2018 at 11:11 am

April 16, 2017 at 1:33 pm

Caryn-C September 11, 2017 at 12:07 pm

Jeff Camp October 1, 2018 at 11:18 am

Robin Pendoley October 11, 2021 at 1:51 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder October 13, 2021 at 5:31 am

Jeff Camp - Founder October 13, 2021 at 5:31 am

Sherry Schnell April 6, 2015 at 8:37 pm

Mary Perry April 7, 2015 at 1:19 pm