What is a school? Before the COVID-19 pandemic, most would have answered this question without much hesitation as a physical place — a set of buildings a where kids and teachers meet for classes, then go home. This answer was never quite right, was it?

In This Lesson

What community services should a school offer?

What is a community school?

What is the history of community schools?

What is expanded learning?

Should our school district create a promise neighborhood?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

Some communities take a broad view of the roles of schools — especially in years when the budget smiles. The general idea is that when schools coordinate the services of the education system with services from other organizations and agencies, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. It's a fragile concept with a long history, often described as the community schools movement. This video from Los Angeles County Office of Education explains:

History of community schools

A community school combines support from many sources to address student and community needs. The heart of this strategy is to coordinate efforts among agencies that are separately managed and separately funded, but that have some goals in common. Community schools programs aim to coax these separate organizations into alignment.

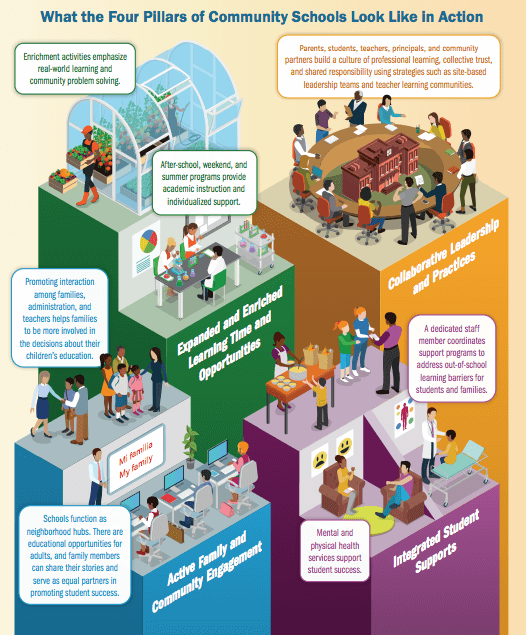

Four Pillars of Community Schools: Click to view the infographic from the Learning Policy Institute.

Four Pillars of Community Schools: Click to view the infographic from the Learning Policy Institute.

The idea that schools must contend with the non-academic factors in students' lives is not new. Community schools can be traced to the settlement house movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, which began in the US with the famous Hull House in Chicago founded by Jane Adams.

During the twentieth century, when local communities were authorized to raise their own taxes to fund their local schools, some California public schools could afford a wide variety of support services, including nurses, social workers, assistant principals, counselors, art teachers, physical educators and other professionals. After Prop. 13 passed, tax revenue eroded even in the best-off school districts. Support positions began to disappear. Communities looked to other agencies for support.

In the 1980s, education leaders began to talk in earnest about serving the whole child, training teachers and administrators to recognize students’ non-academic needs. The terms wraparound services and case management began to be used.

Not all programs survive.

The state legislature enacted the California Healthy Start Support Services For Children Act in 1991, a year of recovery from economic recession. Under this program, school districts competed for flexible grants to provide support services for students. Many Healthy Start districts expanded after-school programs to include support programs, counseling, tutoring and family services. These grants followed the classic structure of pilot program funding — three years of public funding, with the hope that successful programs would attract outside funding, or that school districts would allocate funds to continue them.

The program didn't survive. As schools struggled to keep their counselors, nurses and after-school programs, as well as to keep up with increased regular costs including teacher compensation, there wasn't enough money to go around. The Healthy Start program met its demise in the market bust of the early 2000s.

The pandemic, Gavin Newsom and community schools

Governor Newsom has been a longtime supporter of community schools — in San Francisco, where he was mayor, substantial funding for community schools is included in the city budget. As Governor, Newsom sought to replicate this kind of collaboration among goverment agencies, notably through Communitity School strategies. During the post-Pandemic stock market surge, Newsom urged a massive expansion of such programs.

Expanded learning

Newsom's support for community schools in California has echoes elsewhere. Community schools enjoyed federal support under the Obama administration's Promise Neighborhoods initiative, a grant program that supported cities in replicating a program that proved successful in the Harlem neighborhood of New York. The program was defunded under the Trump administration, but restored and expanded in the Biden administration.

For schools to do more than educate kids in class, it makes sense to have a vision that extends beyond the school day. After-school strategies for learning are often called expanded learning, as described in Ed100 Lesson 4.7. In the recovery from the pandemic, community support for expanded learning was a key budget priority for both the Newsom administration and the Biden administration.

Designs for after-school and expanded learning programs have been strongly influenced by successful examples that blend the two concepts. One of the most acclaimed is the Harlem Children’s Zone in New York City. This video from Edutopia about New York's Children's Aid Society helps to show some of the possibilities.

Why are Community School programs fragile?

When state funding falters, Community School programs are almost always at risk.

In general, state funding for Community Schools is provided in the form of grants. When budgets permit, funds for programs are created, renewed, or expanded, usually through non-profit agencies or programs. When budgets tighten, the money dries up, either quickly or over time depending on the terms under which the grants were made. Programs that rely on relationships and trust between organizations are hard to build, and they wither easily. Changes in leadership or strategic priorities can also undermine collaboration.

Under such inconsistent conditions, it is difficult for community programs to demonstrate their worth in rigorously measurable ways, which makes sustaining them even harder. The leaders of these inter-agency collaborative programs have to be more than just savvy administrators. They also need to be well-connected, persuasive storytellers to secure funds when the agencies involved are struggling to keep their core funding.

Learn more

A well-run community school doesn’t just happen. Community school leaders have identified best practices, incorporated into the State Board of Education’s frameworks to assist schools in implementing the community school model.

Learn more about community schools in this post on the Ed100 blog. For an example of a community school in action, read the post How to Turn Around a Middle School

The next lesson addresses one of the most important factors driving a school's success or failure: leadership.

Last updated March 2024.

Quiz×

CHAPTER 5:

Places For Learning

-

Places For Learning

Overview of Chapter 5 -

Where Are the Good Schools?

Zip Codes and School Quality -

School Choice

Policies for Placing Students -

Selective School Programs

How Schools Sort Students -

Continuation Schools

When Regular School Doesn't Cut It -

Charter Schools

Public Schools, Different Rules -

Private Schools

Tuition, Vouchers, and Religion -

Community Schools

Services Beyond Classwork -

Principals and Superintendents

The Pivotal Role of an Educational Leader -

School Facilities

What Should a School Look Like? -

School Climate

What Makes a School Good? -

Small Schools

Are They Better? -

Home Schools

How Do They Work? -

School Discipline and Safety

Suspensions and Other Options

Related

- There are no related lessons.

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Carol Kocivar September 18, 2025 at 2:31 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder November 17, 2022 at 6:58 am

Carol Kocivar August 3, 2022 at 8:33 pm

To further support the implementation of community schools in communities with high levels of poverty, the state 2o22-23 Budget includes additional funding of approximately $1.1 billion one-time Proposition 98 General Fund to assure that eligible local educational agencies interested in applying on behalf of its high-needs schools have access to the community schools grants.

Carol Kocivar May 13, 2022 at 1:40 pm

The following is the proposed list of 2021–22 California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP) Implementation Grant Cohort 1 grantees.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/13FqOb6jaL_6p4CgNAoZ_Pg1-mwVl2Iuz/mobilebasic

Jeff Camp - Founder February 7, 2022 at 8:07 am

Carol Kocivar October 19, 2021 at 1:14 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder February 13, 2021 at 12:56 pm

Susannah Baxendale January 25, 2019 at 4:14 pm

Caryn January 30, 2019 at 9:42 am

Carol Kocivar July 15, 2016 at 10:10 am

This report outlines six essential strategies for Community Schools and the key mechanisms used to implement these strategies.

https://populardemocracy.org/sites/default/files/Community-Schools-Layout_021116.pdf

Jeff Camp - Founder October 19, 2015 at 10:24 am

a better understanding of how they could integrate these

services into the school."

A shortcoming of this sort of investment is that school leaders often move on.

Elaine Weiss April 29, 2011 at 1:09 pm

While federal, state, and local budgets are very limited, we need to remember that this is a wealthy country that, at the very least, should be able to provide for all of its children's needs and enable them to fulfill their potential.

Serena Clayton April 27, 2011 at 8:56 pm

Serena Clayton April 27, 2011 at 5:14 pm

One of the areas of work of the California School Health Centers Association is to make the case for school health in the health policy arena. We need to build a bridge between these two very different policy worlds - health and education - to make the case that if each deploys some resources toward school health services (as described in the Oakland example), it's a win, win.