Most kids attend the school closest to where they live. It's often the only choice.

In This Lesson

Why are schools local?

What determines where I will go to school?

How did schools become segregated?

What were red lines?

Who assigns students to schools?

What did Brown v. Board of Education do?

How do school attendance areas work?

How were schools desegregated?

Have schools become less segregated or more?

Did school desegregation busing work?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

This chapter of Ed100 focuses on the where of learning. Other chapters focus on matters of who, why, when, what, or how. The 13 lessons in this chapter explore the physical and metaphorical places where learning happens, or is meant to.

What is a local school?

Wherever you live in California, your address belongs to the geographical domain of one public school district. In that district, your kids have the right to attend school at no cost. If the district operates more than one public school serving your grade level, which school is yours? Districts have the power to answer that question, and do so in different ways, which we will explore. You might also have the option to enroll in a public charter school, if they operate in your district and have open seats. A school transfer might be possible, too. But it all starts with your address.

Why? Here's the simplified version…

As we've already pointed out, the history of public schools in America is tangled up in the history of America. The US Constitution doesn't mention education at all, so responsibility lies with each state. California, like most states, delegates most of its responsibility to a geographically-defined quilt of local school districts, from tiny and rural to huge and urban. Los Angeles Unified School District, America’s second-largest, serves close to half a million students. The boundaries of these districts were set through local laws, usually so long ago that no one remembers why… and if they do, the answer might be tinged with racist overtones.

Historically, local schools relied on local taxes.

Until the 1970s, local public schools in California were funded by local property taxes. School boards were very powerful at that time — notably, they set property tax rates, which varied from one district to another. Where you lived determined which school district could tax you, and at what rate.

It was a massively inequitable system. Rich communities with high property values could raise funds for their schools easily, even if they set tax rates low. Poor communities, by contrast, couldn't raise enough money to run good schools no matter how high they set their rates. They were just out of luck.

Today, districts are funded through a formula

It was an unfair system. As Ed100 Chapter 8 will explain, California's courts spurred voters to overhaul it in the 1970s, especially with the passage of Proposition 13 and Proposition 98. These initiatives amended the state constitution in a way that severed the connection between local property tax revenue and school funding.

Bits of the old system remain. In 2022-23 there were 112 school districts in California that collected enough property taxes to fund their schools without significant state revenue support. These basic aid districts served about 3.7% of students in the state many (not all) in Silicon Valley. The most famous famous basic aid district might be Beverley Hills Unified.

Virtually all school districts in California now depend primarily on state income taxes, not local property taxes, to fund their schools. The budget of each school district is calculated on the basis of a consistent statewide formula that involves the number of students attending and their needs. Property wealth plays no role in it. Ed100 chapter 8 gets into more detail about the formula (LCFF), and about the school finance system. But for this lesson, it's enough to understand that school districts are mostly funded on the basis of attendance, and mostly from state money.

For districts and charter schools to get the funding they need, attendance matters. They receive funding for students that show up, regardless of where they live. Districts don't have a serious financial reason to care about where students live, but old habits die hard. Establishing proof of residence is standard operating procedure for schools, even if they have open seats. If you want to cross a line to attend a school outside of a district's territory, it can be complicated. We'll take that up in Lesson 5.2.

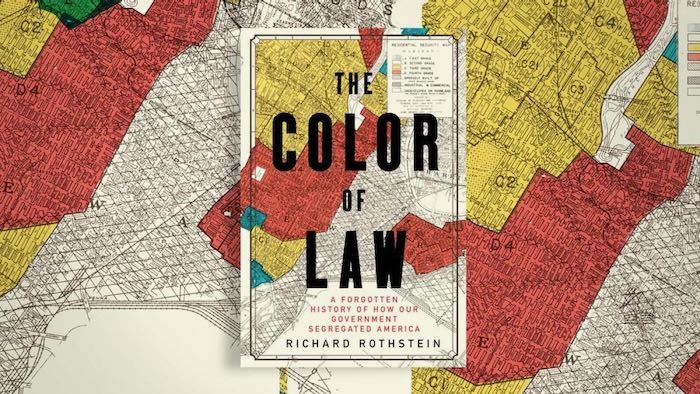

What were red lines?

School district boundaries and the attendance areas within them reflect some ugly history. Not so long ago, racist laws in California determined where people could rent or buy a home and where kids could go to school. Policies known as red lines left scars you can still see in school district maps and school catchment areas within those maps.

Parents, students, and real estate brokers tend to care a lot about these policies. If you live on this this side of the tracks, you go to this school. If you live on the other side, you go to that one.

Gloria Romero, a former California State Senator, calls zip codes "five digits of separation" Some parents will go to great lengths to get their kids into the “right” school. To get away from the “wrong” school or into the “right” one, some parents will lie about their address, even at the risk of being sent to jail for it.

How are students assigned to schools?

The rules for school enrollment, assignments and transfers within each school district are determined by that district. Some districts assign students to schools with a map alone. Some use a lottery. Some provide preferences for siblings to attend the same school. The rules vary a lot and they are entirely local. Your school board has the power to change them.

School assignment policies matter to families. If they don't like their school and they have the money, some families will borrow huge sums to move to a different home. Families time their moves to minimize disruption, even if it costs more. In wealthy areas, real estate agents are experts about local schools and school assignment policies.

Race and school assignment

The role of race in school assignment has long been a matter of critical national concern. In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that to separate children in school “from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may effect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.” The court held, therefore, that “separate” education was “inherently unequal.”

Overall, America is a diverse country with people from all kinds of backgrounds. But the diversity looks more impressive from a distance than it does up close. Many schools are not diverse at all. As the charts below indicate, white students in America tend to attend schools where most students are white. Latino students tend to attend schools where most students are Latino. Black students tend to attend schools where most students are Black.

Visualizing segregation and its effects

The Urban Institute has invested considerable creativity in the work of making segregation visible through data and maps. Search their work to see patterns in your area.

In a series of huge economic studies, Opportunity Insights and the US Census Bureau partnered to create the Opportunity Atlas, a free, interactive mapping tool that "estimates children’s chances of climbing the income ladder for 70,000 neighborhoods across America." The tool helps reveal the role that school districts continue to play in blocking social mobility in America.

Schools are central to patterns of social connectedness or isolation. Work by Raj Chetty and others using Facebook data establishes that these patterns have lasting consequences including economic and civic outcomes. By these measures, those in California's central valley are particularly isolated.

Education in rural schools

Educational results in California's rural districts severely lag results in more urban districts, a topic investigated by EdSource in 2019 and again in 2024. Rural districts depend disproportionately on Federal grant support, which the Trump administration declared its intention to cut significantly in 2025.

Buses and school integration

The Brown decision compelled many school districts to integrate their schools. It was a difficult and disruptive order, because many families live in segregated communities. In some large districts such as Los Angeles, for a time desegregation orders required children to ride buses to schools outside their own neighborhood.

It's important to know that from an education point of view, desegregation worked. Overall, more students did better in school. But forced busing was widely unpopular from the start. Voters amended the state constitution in 1979 to end it.

Over time, additional court decisions (especially Milliken v. Bradley) ended court-ordered busing in America more broadly.

Not all students have a choice of schools, but some do. Does choice tend to make segregation better or worse? Read on to lesson 5.2 to find out… but first take a moment to pass the quiz below and earn your ticket. It leads toward your certificate as an Ed100 Graduate!

This lesson was updated in October 2025.

Quiz×

CHAPTER 5:

Places For Learning

-

Places For Learning

Overview of Chapter 5 -

Where Are the Good Schools?

Zip Codes and School Quality -

School Choice

Policies for Placing Students -

Selective School Programs

How Schools Sort Students -

Continuation Schools

When Regular School Doesn't Cut It -

Charter Schools

Public Schools, Different Rules -

Private Schools

Tuition, Vouchers, and Religion -

Community Schools

Services Beyond Classwork -

Principals and Superintendents

The Pivotal Role of an Educational Leader -

School Facilities

What Should a School Look Like? -

School Climate

What Makes a School Good? -

Small Schools

Are They Better? -

Home Schools

How Do They Work? -

School Discipline and Safety

Suspensions and Other Options

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Jeff Camp February 26, 2020 at 1:10 pm

Sonya Hendren August 12, 2018 at 10:52 pm

http://www.lozanosmith.com/news-clientnewsbriefdetail.php?news_id=2541

Of course, this is not as solid as residency, because the districts might not approve the transfer.

The new (2015) nanny/care-giver rule gives residency (so no need to apply for a transfer) to students who live with their parent, at their parent's place of work within the school district, at least 3 days of the school week. ["Parent" meaning parent or guardian]

Jeff Camp July 30, 2018 at 11:07 am

Jeff Camp June 6, 2018 at 5:02 pm

Jeff Camp May 8, 2018 at 11:44 am

Evan Molin February 22, 2018 at 5:18 pm

NATHANIEL CAUTHORN February 22, 2018 at 8:33 am

#whereisthejustice #youknowwhattodo

Arianna Stamness February 22, 2018 at 8:28 am

AlessandroMiguel Amores February 22, 2018 at 8:27 am

Jordan Rohr February 22, 2018 at 8:26 am

Grace Thomas February 22, 2018 at 8:26 am

Ethan StLouis February 22, 2018 at 8:26 am

Alyssa Stettner February 22, 2018 at 8:26 am

Emma Mechelke February 22, 2018 at 8:24 am

February 22, 2018 at 8:23 am

VICTOR NGUYEN February 22, 2018 at 8:22 am

Brooklyn February 22, 2018 at 8:19 am

Connor Pargman February 22, 2018 at 8:17 am

Hannah Symalla February 22, 2018 at 8:15 am

Abigail Hennessy February 22, 2018 at 8:09 am

kevin October 8, 2017 at 4:51 pm

Caryn-C October 10, 2017 at 8:41 am

Jeff Camp - Founder July 29, 2016 at 9:37 pm