What happens when a school isn’t getting the job done?

In This Lesson

How do you fix a failing school?

What is the Anna Karenina principle?

What happens in a failing school?

Is funding part of why schools fail?

What was No Child Left Behind?

What is ESSA?

Should bad schools be closed?

Are charter schools an option?

How does the state help struggling schools?

What is the Statewide System of Support (SSOS)?

What is CCEE?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

Public education systems in America (and in much of the world) invest heavily in each child’s future, providing 13 years of free education in schools staffed with professional educators.

This lesson explains how California’s education system is meant to respond when a school isn’t serving kids well. The answer has changed over decades.

There is no magic answer

Education leaders and experts have struggled for years to find effective strategies to address dysfunctional (or “failing”) schools. Business as usual is a recipe for more of the same, so what should be changed? Is it best to replace the leadership? Hire different teachers? Flood the existing faculty with resources? Send in a training team? Buy a different curriculum and persuade faculty to adopt it? Do you try to address issues outside of education, like housing insecurity or family stresses?

The net conclusion of decades of research is that there is no magic answer. Each school is different. If there were an easy way to fix dysfunctional schools, it would have been found by now. Big, entrenched challenges require disruptive changes, sustained effort, and money — and even then they don’t necessarily work because school systems are people systems.

The Anna Karenina principle

It makes sense that broken schools are so hard to repair. The core problem is a variant of the Anna Karenina principle: Functioning families are all alike; malfunctioning ones each struggle in their own way.

Functioning schools are all alike; malfunctioning ones struggle each in their own way.

Like families, schools are groups of real people, each with their own challenges. In a high-functioning school, the hard work of learning takes center stage each day, even in the face of conflicts, shortages, distractions, and (gasp!) puberty. Schools aren’t unique in their vulnerability to dysfunction; many grown-up organizations struggle, from businesses to churches to unions. When habits form, they are hard to break. Strategies that work in one place are frequently ineffective in another.

This reality should be a call to action. Every school has to work.

Failure is not an option. What is success?

Each kid only gets one childhood, and we all share a stake in their success. Improving school systems is urgent work.

As explained in Ed100 Lesson 1.7, the history of the education system has been a gradual fumbling toward huge expectations for public schools. Over time, society’s definition of success has expanded to include all kids, not just the ones that are convenient to teach. As Lesson 8.1 will show, these expanding expectations have not been matched with expanded resources (Lesson 8.1). We expect more from public schools, but spend less effort to fund them. Here's a preview:

The idea that schools should be universally successful was enshrined in federal law with passage of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, 2002-2015). It was a tough, top-down policy that forced school systems to make disruptive changes, particularly if they didn’t address achievement gaps and make adequate yearly progress (AYP) toward grade-level proficiency in annual tests. As explained in Ed100 Lesson 7.2, the public liked the idea of this policy at first, but soured on it as more and more schools were told that their school wasn’t meeting expectations. At the end of the Obama Administration, Congress called it quits, replacing NCLB with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA, 2016-present), a less demanding policy.

How is ESSA different from No Child Left Behind?

The ESSA law requires states to officially notice persistently struggling schools, but in much fewer numbers and with much less specific requirements than NCLB did. Under ESSA, each high-poverty district receives federal funding to support schools that most need support, focusing on 5% of students. The method of identification is left to each state. In California, schools eligible for Federal assistance are determined by indicators on the California School Dashboard, explained in Ed100 Lesson 9.7.

Federal ESSA grants for school improvement come in two flavors: comprehensive (CSI) and targeted (TSI/ATSI). Funded through the federal Title I program, both programs specifically support schools where many families have low incomes. TSI/ATSI grants specifically target improvement in schools where particular groups of students are significantly behind.

Intervention is optional

ESSA doesn't clearly specify how states and districts should intervene in persistently low-performing schools using CSI and TSI/ATSI grants. Some see this flexibility as federal humility — it leaves states and districts free to choose the best course of action. Others see it as federal cowardice — all carrot and no stick, it leaves states and districts essentially free to do nothing. The federal Department of Education suggests effective options through the What Works Clearinghouse.

Unfortunately, turning struggling schools around turns out to be really, really hard.

California’s system for allocating core funds to districts (LCFF, explained in Ed100 Lesson 8.5) is based on a consistent set of rules that harmonize well with ESSA’s priorities. (Simplifying a lot, schools with greater needs receive more funding.) Because California’s education system invests less funding effort in public education than other states do, school turnarounds are probably even harder here than elsewhere.

Should dysfunctional schools be closed?

Unfortunately, no known magic can transform dysfunction into alignment or transmute money into learning. School improvement efforts require steady, uncomfortable work with the active involvement of teachers, parents, kids, teens and other humans. School districts rarely close a school in response to a pattern of bad results — it seems like giving up — but the unsurprising truth is that improvement efforts often fail. One particularly frank study of school turnaround efforts described low-performing schools as immortal, suggesting that families are better off moving their kids to a better-functional school than hoping for change to happen in a relevant timeframe.

Extending this view, advocates for school choice argue that families in low-performing school attendance zones ought to have the right to transfer their children to higher-performing ones. They don’t, except in a few school districts that have decided to allow it. Why not? The reasons are partly financial; school districts are funded on the basis of attendance. When students are allowed to transfer away, funding goes away with them.

Uncertain funding is a huge challenge for underperforming schools. As described in Ed100 lesson 1.1, California is no longer growing explosively. Partly due to the unintended incentives of Proposition 13, housing turnover in established school communities has declined, pushing young families out. Enrollment has fallen in many districts, leaving schools under-enrolled. As demographic shifts play out, districts under financial pressure are facing the difficult work of closing schools in increasing numbers. The possibility that a struggling school might be closed makes turnaround efforts even harder.

Charter schools as an alternative

When families see their local school as low-performing, they look elsewhere. Concern about school quality has been one of the forces behind the growth of public charter schools, as explained in Ed100 Lesson 5.5. Where a charter school exists, parents residing anywhere in the district have the option to enroll their child if a spot is open. No permission is required for the transfer. This option works for some families, but not all charter schools are better.

California’s school turnaround agency: CCEE

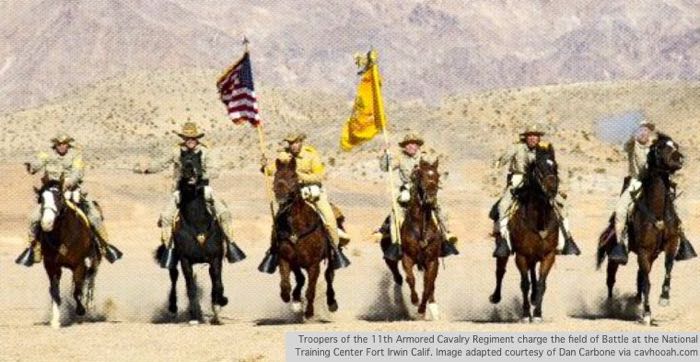

Call in the cavalry!

Of course, the ideal solution would be to transform all troubled schools into good schools. In the long search for turnaround strategies that work, federal funding has been esssential. Famous efforts include School Improvement Grants and the competitive Race to the Top program. California has also pursued its own long-forgotten experiments, HPSGP and II/USP and QEIA.

None of of these projects worked miracles, but all produced outcomes. Race to the Top, in particular, created the conditions for many states (including California) to adopt shared educational standards. In some states, districts adopted data systems that support improvement in teacher practices and student learning progress. Using this data, curriculum developers were able to improve their materials and assessments.

In 2013, as the NCLB era came to a close, California's legislature created the California Collaborative for Education Excellence (CCEE), a state agency tasked with providing guidance for bottom-up improvement efforts in schools and districts. A widely-admired school leader, Carl Cohn, assumed leadership of the organization, bringing immediate credibility. In 2017, the CCEE played a central role in the rollout of the California School Dashboard, which helps reveal durable patterns of success and failure in each school and district.

Echoing the federal shift from NCLB to ESSA, California’s strategy for addressing low-performing schools evolved away from focusing on accountability for results toward an emphasis on building school districts' capacity to succeed.

California's Statewide System of Support (SSOS)

As of 2025, California's legislature has transformed CCEE into the coordinating agency of a decentralized statewide system of support (SSOS) that draws on the growing expertise of County Offices of Education throughout the state.

To learn about the services available and how they mesh, see the 2023-2024 CCEE annual report — it’s impressively practical. Some categorical funding programs that address particular needs have also been folded into the framework of the state system of support, providing improved structure and oversight for them. The website of the State Department of Education includes details about programs and funding.

The federal emphasis on building districts’ capacity to improve schools aligns well with California’s self-help approach to school district accountability, the LCAP. The next lesson explains how it is meant to work.

Creating a strong system of schools requires getting many things right at the same time, consistently. Change can be demanded top-down, but successfully improving a big system requires building capacity bottom-up. Developing the capacity to support change in each struggling school is a difficult undertaking, but it's the only non-magical answer available. After the cavalry comes to the rescue, it leaves.

This lesson was updated in January, 2025.

Quiz×

CHAPTER 7:

And a System…

-

And a System…

Overview of Chapter 7 -

The Role of State Government in Education

California’s Constitutional Responsibility -

The Federal Government and Education

Small money, Big Influence -

School Districts in California

What do School Districts Do? -

County Offices of Education

Oversight and Regional Services -

Teachers' Unions in California

What do Teacher Unions Do? -

Ballot Initiatives and Education

California's Initiative Process and How It Affects Schools -

Who Influences Education?

Politics, Philanthropy and Policy -

Accountability in Education

Who Monitors the Quality of Schools? -

What to Do with Failing Schools

Interventions and Consequences in California -

The LCAP

Annual Plans for California School Districts

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Jeff Camp - Founder July 11, 2024 at 9:56 am

Jeff Camp February 27, 2019 at 9:38 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder August 23, 2015 at 6:47 pm

digalamedabg April 14, 2015 at 9:26 pm

woodmiddleschoolpta April 2, 2015 at 4:26 pm

cnuptac March 26, 2015 at 11:27 am