In every state, funding for public education comes from a combination of state taxes, local taxes, and some federal money.

In This Lesson

Do property taxes pay for schools in California?

How are public schools funded in California?

How much federal money pays for education in California?

How much does California's lottery help public schools?

Can school districts in California set property tax rates?

Where does funding come from for public schools?

What is Serrano v Priest?

Why are property tax rates the same everywhere in California?

What was Proposition 13?

What do property taxes pay for?

What is a Basic Aid district?

Why are California budgets so volatile and uncertain?

What is Prop 2?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

The mix of sources varies a bit from one state to another, and it can change over time. Where does the money for public education come from?

Let's dispense with the smallish part first: The federal government usually plays a pretty minor role in funding California's K-12 schools — normally less than a tenth of total K-12 expenditures. Most of the ongoing money is allocated to schools or districts on the basis of poverty-related formulas. In times of fiscal crisis such as the aftermath of the Great Recession (December 2007 to June 2009) or the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-22), however, temporary federal support is crucial because the federal government can run a deficit. California's state constitution forbids it from doing so.

Most of the money for public education in California comes from two big sources: state income taxes and property taxes — in that order. These taxes power the education system, as well as many other functions of government.

Let's back up the camera. It's helpful to put the big picture in context.

California's three-part tax system

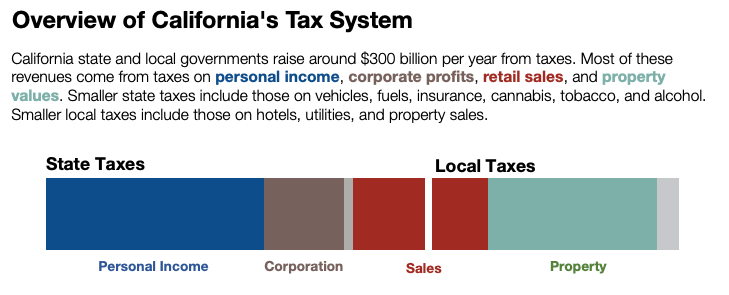

California's overall tax system consists of three roughly equal parts: personal income tax, property tax, and sales and use taxes. Education is funded by a mix of these sources, especially the first two. The schematic diagrams below, from the California Legislative Analyst Office (LAO), summarize the major sources and uses of funds.

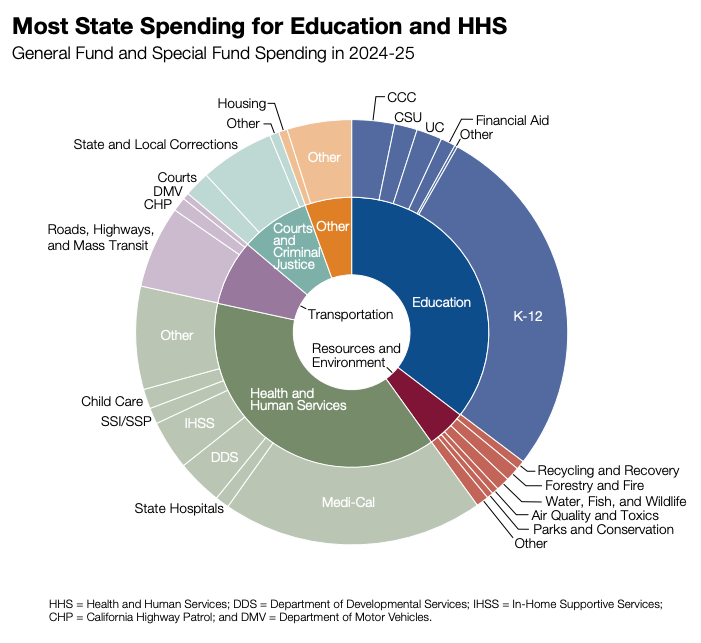

How are these funds used? The LAO summarizes it in the schematic chart below.

Budgets are the complex, messy output of a political system. There is not a clear, easy-to-describe mechanism that determines which taxes are collected (revenue) and the purpose toward which they are allocated (expenditures). Income taxes, for example, support both school systems and municipal functions. The same is true of property taxes.

Sources of funds for public education in California

The chart below summarizes the main sources of general operating money for K-12 education in California. The way the pie is sliced doesn't tend to change radically from year to year, except in times of crisis, when federal funding might temporarily increase. The rest of this lesson examines each education-related slice of the pie more deeply.

How much do schools get from property taxes?

Long ago, throughout the United States, property owners substantially shouldered the cost of local schools by paying local taxes based on the value of their property.

Over time, however, property owners demanded change, especially through Proposition 13, which Lesson 8.4 will explain. In California, property taxes are no longer the main source of revenue for most public schools.

Property taxes are the revenue source for many local government functions, and county auditors play a key role in divvying up the money. It can get messy, and school districts have not always received their due slice. It's a weedy issue, but if you feel like following it, look for news about Educational Revenue Augmentation Funds (ERAF).

How much do schools get from state income taxes?

The biggest source of revenue for schools in California is state income taxes. This has been true since the late 1970s, after the passage of Proposition 13.

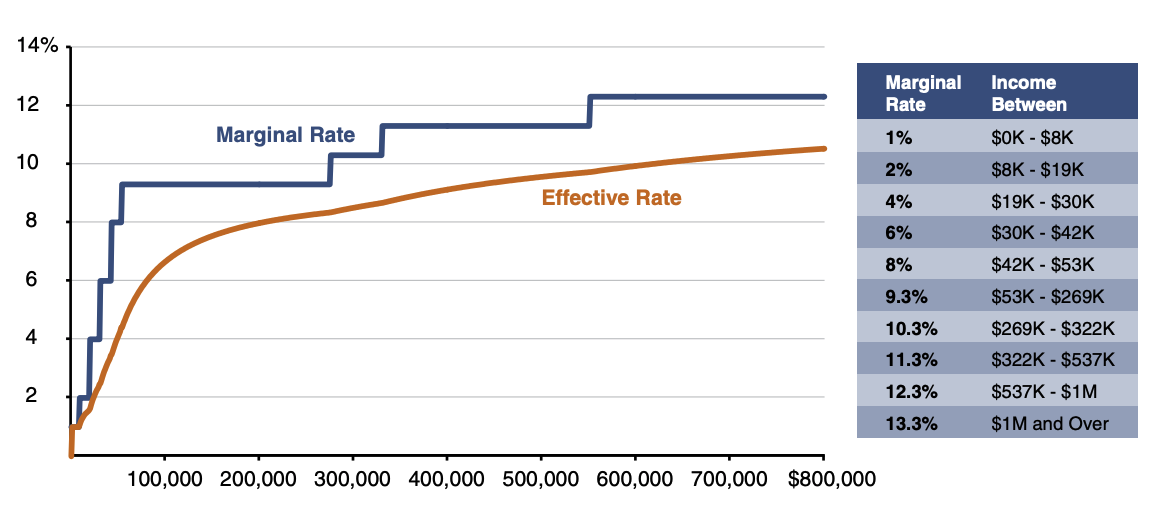

This may seem obvious, but income taxes are paid by people who have income. The majority of Californians pay little or no state income tax. California's income tax system is progressively indexed into nine tax brackets, which means that larger incomes are taxed at higher rates than smaller ones. California's top marginal income tax rate, 13.3%, is paid by about 90,000 of the state's top earners on the portion of their income above $1 million in a year.

Marginal income break points shown in this chart are from 2018, but the shape of the curve is unchanged. Effective rates are lower than marginal ones.

About half of California's income taxes each year are collected from that year's biggest income earners — the proverbial 1%. In 2021, half of all state personal income taxes paid in the state came from 158,444 taxpayers with Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) of more than $1 million. Taxes paid by the top 8,519 earners, each with single-year income surpassing $10 million, collectively amounted to about a quarter of all personal income taxes that year. (Calculated from Franchise Tax Board data set B-3, via California Open Data Portal.)

These top taxpayers tend to live in a few areas of the state. In 2016, California collected over $1 billion in taxes from individuals in a single zip code in Palo Alto. (Check your zip code using the CalMatters map, How Much Do Your Neighbors Pay in California Taxes?)

How much do California schools get from the lottery?

California voters created the State Lottery in 1984. It's a big operation with about a thousand employees and a substantial marketing presence. About half of all adults in California buy at least one lottery ticket each year, knowing that — win or lose — a portion of the price of the ticket goes to support California’s public K-12 schools and colleges.

Because the lottery is well-marketed, it's easy to overestimate its role in funding education.

After prizes and expenses, the lottery pays for about 1% of the California education budget, very roughly equivalent to about $200 per student. Learn more about the lottery in the Ed100 blog or from the filings of the state lottery commission.How much do California schools get from other local funds?

The Other Local slice, about 12% of the funding pie in a typical year, is generated and controlled by local school districts. This sliver includes interest income, income from leasing out unused property, oil and gas wells on school district property (yes, really), parcel tax proceeds, donations, and a salad of other miscellaneous sources. (You can find your district's sources of revenue in the District Financial Reports on the Ed-Data website.)

With rare exceptions, the state apportions education dollars to districts based on a calculation known as the Local Control Funding Formula, explained in Ed100 Lesson 8.5.

In a moment, we'll examine how California's education funding system evolved to its current form. But first, a quick recap:

| Recap: California's funding system for school operations | |

|---|---|

| Income taxes | The biggest source. The state's education system relies heavily on wealthy individuals making money and paying a lot of taxes. |

| Property taxes | Important, but rarely sufficient to fund the cost of local schools. |

| Federal funds | Generally provide less than a tenth of the money for public education, except in times of crisis. |

| Other local sources | Vary a lot, and we'll cover some of them in Lessons 8.9 and 8.10. |

| The Lottery | Raises about 1% of the budget for public schools. |

| LCFF | The Local Control Funding Formula determines how much your school district actually gets from the state. (Consider this foreshadowing. We'll explain it in Lesson 8.5) |

How did California end up with this approach to funding K-12 education?

The courts and voters put the state in charge

The source of funds for schools in California changed dramatically in the late 1970s. (chart data)

Until the late 1970s, California, like most states, funded its schools through local property taxes levied at rates set by local school boards. The amount raised for local schools varied a lot, depending on the local tax rate and the assessed value of local homes and commercial properties. County assessors held the important job of determining the taxable value of each property.

This arrangement was great for property-rich districts, but rotten for communities with low assessed values and lots of students.

This arrangement was great for property-rich districts, but rotten for communities with low assessed values and/or lots of students. Those communities had to set very high property tax rates to provide schools with as much money per student as their more fortunate counterparts. Serrano v Priest, the first in a series of landmark court decisions, challenged this arrangement in 1971. Is it really fair, the case asked, that some districts can tax themselves at a lower level and still enjoy more funding per student than others? After all, kids have no say in the wealth of their parents. The case led to court-mandated revenue limits, which were meant to equalize funding per student at the district level over time.

Voters passed Proposition 13 in 1978. Among other things, the proposition amended the state Constitution to set a limit on property tax rates at 1% of assessed value. The measure removed the power of school boards to levy local property taxes for local schools. To prevent education funding from plummeting, the state legislature stepped in, allocating state funds from a budget surplus to protect schools from what would have otherwise been massive cuts.

Suddenly, school districts had no local control over the amount of money available to fund their schools. Among the unintended consequences of Proposition 13, it centralized power over the education system in Sacramento. The state legislature and the governor became responsible for determining how funding would be distributed to districts. School boards, once powerful and independent, were left with the narrower job of playing the hand dealt to them by fate and the state.

Another provision of Proposition 13 insulated property owners from higher taxes by freezing assessed values, allowing them to rise at a maximum annual rate of 2% regardless of their actual market value. Existing owners of residential and commercial property benefited enormously from this provision, as the market value of their property skyrocketed at a compound growth rate of about 6% and rent rose by 8%. The median listed value of a California home in 1980 was about $84,500. In 2022 it was about $834,000. (For more on Proposition 13, continue to Lesson 8.4.)

Politics shifted along with funding control

Public schools in California are often thought of as local schools, but in many ways, it is useful to think of them as state schools. As discussed in Lesson 7.1, it is the state that bears the constitutional responsibility for public education, not school districts.

The old system was nuts.

Until 2013-14, education finance policies apportioned funds to districts based on a bizarre system of revenue limits. If you have a masochistic interest in California's historical school finance laws, knock yourself out. If not, better to spend your time understanding the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), explained in Lesson 8.5. It's a simpler and fairer system that replaced the rusty old plumbing of revenue limits and categorical funds.

Nowadays virtually all school districts in California (about 97% of them as of 2023) rely on state funding, because their local property taxes generate insufficient funds to reach the base level per student guaranteed by the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). (More about LCFF in Lesson 8.5.)

There are some exceptions. For example, if the boundaries of a school district include valuable commercial property, the property taxes generated are sometimes enough to fund the district beyond the base level. In California education jargon, these are officially known as community-funded districts, but they are often (somewhat misleadingly) referred to as basic aid districts.

The role of political will in school funding

Nobody likes paying taxes. Passing a tax measure requires political will — a level of collective agreement that can overcome apathy, distrust, and competing priorities. It requires trust, too — not just that the money to be raised is needed, but that it will be spent well and make a difference. There are all kinds of reasons to say no.

This is a big, diverse state. It is hard for voters to trust that decisions made in far-off Sacramento will truly benefit local families. Most voters are more inclined to support taxes that benefit their local community schools than ones that apply to the whole state of California.

Serrano and Proposition 13 flipped California's education funding system from a local system reliant on local property taxes to a state system reliant on state income taxes. It made the system fairer, but it also made the system more politically distant.

Income tax revenues are volatile

As discussed above, Proposition 13 triggered a big switch in the source of funding for public education from property taxes to income taxes. This shift brought a new challenge to California school budgeting: volatility.

Property values (and therefore property tax receipts) vary with the economic cycle, but they don't tend to change massively from one year to the next. Income taxes, by contrast, are very exposed to the booms and busts of the stock market. The individuals in the top 1% of income earners in California each year generate about half of the state's income taxes. Individual fortunes can change a lot from year to year, but they tend to have something in common: the stock market.

California's rainy-day fund

To smooth out some of the volatility in state revenues, in 2014, California voters passed Proposition 2, which requires the state to build rainy-day funds in good budget years. It still requires political will to protect against years when revenues fall.

Districts keep reserves, too, but it can be politically difficult to do so. There are always real needs and worthy investments — and if a district builds significant savings, it carries the risk of becoming an attractive target for a lucrative lawsuit.

The next lesson, Lesson 8.4, focuses on the two measures that have had the biggest impact on education funding in California: Proposition 13 and Proposition 98. Beginning in Lesson 8.5, this chapter will explain the allocation process, especially including how the state determines the amount each school district receives under the rules of the Local Control Funding Formula.

Updated January 2025.

Quiz×

CHAPTER 8:

…with Resources…

-

…with Resources…

Overview of Chapter 8 -

Education Spending

Does California Spend Enough on Education? -

Education Purchasing Power

What Can Education Dollars Buy? -

Who Pays for Schools?

Where California's Public School Funds Come From -

Prop 13 and Prop 98

Initiatives That Shaped California's Education System -

LCFF

The Formula That Controls Most School Funding -

Categorical Funds

Special Education and Other Exceptions -

School Funding

How Money Reaches the Classroom -

Do California Schools Waste Money?

Is Education Money Well Spent? -

More Money for Education

What Are the Options? -

Parcel Taxes

Only in California... -

School Volunteers

Stealth Wealth for Schools

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Carol Kocivar March 24, 2023 at 4:47 pm

A 2023 report published by the Albert Shanker Institute explains this problem and proposes a plan to help fix it with a strategic use of federal funding.

It notes: “California, Colorado, Florida, and North Carolina currently exhibit severe and widespread funding gaps despite having the means to rectify them.”

https://www.aft.org/ae/spring2023/baker_dicarlo_weber

Jeff Camp - Founder February 1, 2022 at 5:50 pm

Marie Holley November 16, 2020 at 6:22 pm

Jeff Camp November 17, 2020 at 3:50 pm

Leigh Boghoussian February 5, 2020 at 11:20 am

Given the massive lottery payouts that occur each and every week, is there no way to force the contribution to be more than 1%? Has there ever been an attempt to do so?

Jeff Camp February 6, 2020 at 2:02 pm

Iris December 1, 2017 at 7:03 pm

Caryn-C September 11, 2017 at 11:52 am

I also thought it very telling that the solution isn't just taxing the 1% since the personal income tax volatility creates such an erratic money pot.

I'm interested in seeing how our district plans on bumping up education spending per pupil by almost 3,000 in the next three years.

cb65dy89 May 9, 2016 at 8:21 pm

Mark MacVicar May 15, 2015 at 10:29 am

Brandi Galasso May 2, 2015 at 4:17 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder May 3, 2015 at 11:59 am

david_bolling_wells October 30, 2014 at 4:29 pm

"Property taxes are local; they stay where they are earned."

david_bolling_wells October 30, 2014 at 4:40 pm