For teachers in California's traditional public schools, the first two years are make-or-break.

In This Lesson

What is teacher tenure?

When do teachers get tenure?

What is the dance of the lemons?

How can teachers be fired?

What are the ideas for reform of tenure?

What does seniority mean for teachers?

What was the Vergara case?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

What is teacher tenure?

New teachers in California face a steep learning curve and a deadline: For the first two years they work under probationary status and can be dismissed at will. After that, they have a certain degree of job security commonly called tenure, though more technically known as permanent status. (The word tenure is borrowed from higher education. In K-12, unions avoid the term in favor of varying euphemisms.)

California's tenure policy is unusually quick. Most US states require three years and evidence of competence. In California, teachers gain permanent status in two years, which means districts have to figure out within about 18 months whether a new teacher should be made a permanent member of the faculty.

Many teachers start their tenure in boom times

As described in Lesson 3.2, demand for teachers is cyclical. When the stock market rises and budgets increase, lots of school districts want to hire teachers at the same time, creating teacher shortages. In those conditions, it's relatively easy to get a teaching job, if you have the credentials. School districts hire who they can while they can. As news spreads about teacher shortages, districts focus on keeping the teachers they have — including new hires unless they are hopeless.

When the stock market drops, by contrast, California's budget for education falls with it. Districts are obligated to notify teachers by March 15 if they can't guarantee their position for the coming school year. Seniority usually determines the pecking order for these layoff notifications (pink slips).

There have been multiple attempts to reform teacher tenure policies in California. Many have sought to delay tenure by a year or two, since California's policy is unusually quick. Other proposals have sought to make tenure status conditional on evidence of good work. Others seek to reduce the role of seniority as a factor in layoffs or forced placements, or to streamline the steps involved in dismissing teachers.

Dismissals for cause are very rare

To protect their members from capricious dismissal, teachers unions negotiate due process requirements in their contracts with employers.

These requirements can be daunting and costly. Teacher dismissals for cause are exquisitely rare in California, even in cases of egregious misconduct. Statewide, about 0.2% of teachers each year are dismissed for cause.

Serious allegations are escalated to the Division of Professional Practices (DPP), which is meant to report annually on its workload. (As of September 2025 the DPP Dashboard was offline and the most recent web-discoverable report was from 2022-23. If you find a newer report, please contact us!) In 2022-23, the DPP opened 5,740 cases, the largest number of which involved alcohol. Cases take an average of a year to process to closure. In 2023 the CTC closed 699 cases with adverse actions, mainly suspension or revocation of credentials.

Because the process of firing a teacher is difficult, time consuming, uncertain, and costly, principals sometimes use a more expedient solution: they make a deal. If a poorly-performing teacher agrees to move to another school, the principal agrees to award a satisfactory rating and look away. This practice, known as the dance of the lemons, was colorfully derided in Davis Guggenheim’s 2010 film Waiting for Superman (video clip).

In a layoff, who gets fired?

Last hired, first fired.

In negotiation with their unions and within the constraints of employment law, California school districts set their own policies for what happens when layoffs are likely or unavoidable. Each year, by March 15, districts issue pink slips (layoff notices) to employees who need to consider their alternatives. In 2022, the legislature extended this requirement beyond teachers to include classified employees, which means that a legal process is required to lay off just about anyone who works in public education.

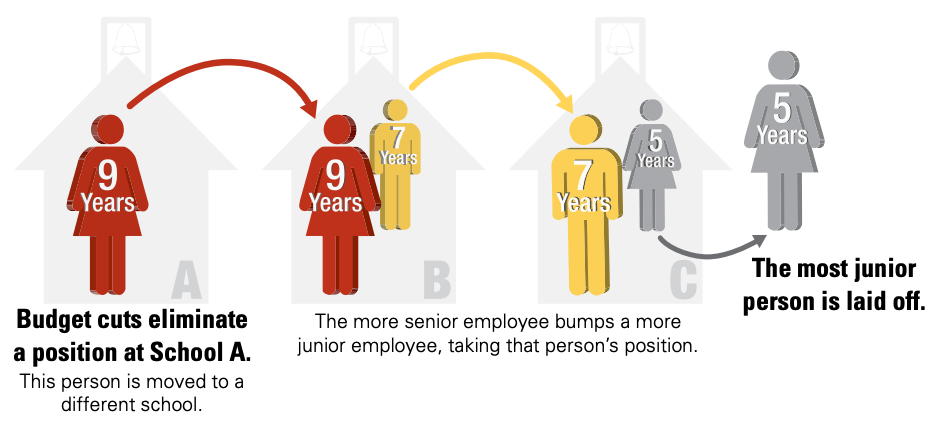

California's largest teachers union, CTA, has taken the position that seniority is the least unfair option when layoffs are unavoidable. According to CTA, “In most cases, the order of layoff must be based on credentials and qualifications; seniority dates; probationary vs. permanent status; and experience. In some circumstances, the district may also consider specialized training and education.” The union provides advice to its members about how to survive a layoff.

Seniority-based layoffs can have devastating effects on students and school communities. In California school districts, the teachers most recently hired are the first let go, regardless of what they teach, how amazing they are, or whether the layoffs will have a disproportionate impact on a particular group of students or a particular school. (Public charter schools may have different policies.)

Seniority-based layoff policies are also known as last-hired-first-fired or last-in-first-out (LIFO) policies.

Education Trust West, a nonprofit organization, explained the impact of seniority-based employment rules coherently in its report Victims of the Churn. The report criticizes "bumping" rights with particular vigor (see graphic above).

The use of seniority as a factor in teacher dismissal came sharply into question in the lean budget year of 2010. Focusing on data in Los Angeles Unified, the ACLU argued that seniority-based provisions had a disparate impact on students in poverty in low-performing schools. After four years of negotiations, the case was settled and 37 schools received additional funds for teacher training.

Some advocates had hoped for a broader set of changes. In 2012, a series of lawsuits (Vergara, Robles-Wong and CQE) sought to strike down tenure and seniority practices in California state law. The suits attracted a great deal of interest, but ultimately failed to bring about change. A three-judge panel didn't dispute that "deplorable staffing decisions being made by some local administrators… have a deleterious impact on poor and minority students in California’s public schools", but concluded that laws regarding tenure and seniority did not "inevitably" cause this impact.

Inevitable harm might be impossible to prove, but that's essentially the standard that the court applied to itself in deciding the case. "The court is without power to strike down the challenged statutes. The court’s job is merely to determine whether the statutes are constitutional, not if they are 'a good idea'.”

In practice, the court kicked the can to the legislature, or future courts, to address the unequal damage caused by layoffs. As of this writing, the underlying policies that allow the "deplorable staffing decisions" remain in place.

In many of California’s school districts, enrollment is declining, so it’s more important than ever to understand the laws about teacher layoffs.

This lesson was updated in September 2025

Quiz×

CHAPTER 3:

Teachers

-

Teachers

Overview of Chapter 3 -

Teacher Recruitment

Who Teaches, and Why? -

Teacher Certification

How Are Teachers Prepared? -

Teacher Retention

How to Keep a Teacher -

Teacher Placement

Who Teaches Where? -

Teacher Development

How Do Teachers Improve? -

Teacher Collaboration

How do Educators Work Together? -

Teacher Benefits

Healthcare and Sick Days -

Teacher Pay

How much are teachers paid? -

Teacher Evaluation

How Do Teachers Know If They Are Succeeding? -

Tenure and Seniority

Teacher Tenure - Good? Evil? -

Pensions

How Good is a Teacher's Pension?

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Lulu Mavi September 18, 2024 at 8:48 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder September 23, 2021 at 1:04 pm

Susannah Baxendale January 14, 2019 at 11:31 am

Caryn January 15, 2019 at 9:23 am

Jeff Camp - Founder April 5, 2017 at 7:11 pm

Jeff Camp January 11, 2017 at 4:39 pm

Albert Stroberg May 1, 2016 at 6:44 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder April 14, 2016 at 11:50 pm

germanb July 7, 2015 at 9:35 pm

Marcellus McRae Presents Plaintiffs' Closing Arguments in Vergara v. California on Vimeo

http://vimeo.com/90273109

Tara Massengill April 22, 2015 at 11:56 am

Jeff Camp - Founder January 15, 2015 at 11:33 am

"71 percent said layoff decisions should be based partly or entirely on classroom performance; 24 percent supported basing layoff decisions almost entirely on seniority."

"15 percent said tenure in two years or less was appropriate"

http://edsource.org/2015/teacher-survey-change-tenure-layoff-laws

Carol Kocivar - Ed100 October 25, 2014 at 1:39 pm

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/1282339-judgement-vergara-judge-affirms-ruling.html

The State has filed a notice of appeal:

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/1283281-teacher-vergara-canoticeofappeal082914.html

Carol Kocivar - Ed100 June 10, 2014 at 12:20 pm

On June 10,2014, the Superior Court of California in a tentative decision found the challenged statutes unconstitutional.

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/1184998-vergara-tentativedecision061014.html

In a press statement, the California Teachers Association advises the decision will be appealed.

http://www.cta.org/en/Issues-and-Action/Ongoing-Issues/Vergara-Trial1.aspx

David B. Cohen April 7, 2011 at 12:59 pm

1. While we all use the word "tenure" it must be clarified that K-12 teachers do not have the same academic liberties that university professors enjoy with their "tenure." The main benefit of "permanent status" is the due process - that administrators must show cause for firing a teacher with that status.

2. There's no denying that a system strictly based on seniority in a district has flaws. I'm quite sympathetic to the view that the needs of a school should be considered, so that you don't keep destabilizing the same campuses over and over. However, I do not trust most of the people who talk about reforming the system because they seem more interested in firing teachers than fighting for adequate funding to avoid layoffs, or robust evaluation systems needed to measure quality (because test scores don't work).

3. Though it's not the stated focus of your post, I hope people recognize that you're pointing out systemic problems; it's not possible to lay the blame at any one doorstep, be it the union, administration, or district. The fixes for this problem will not come from "either/or" decisions, but rather a broad set of solutions aimed at every part of the problem: teacher training and professional development, union willingness to negotiate, improved training and ongoing support for principals, reformed governance and procedures especially for large districts, and most importantly, adequate funding for schools.

Dominic Brewer April 12, 2011 at 12:10 pm