In California, voters can directly change the state's constitution by passing an initiative. Two voter actions have affected public education deeply: Proposition 13 (1978) and Proposition 98 (1988).

In This Lesson

What was the Serrano v. Priest case?

Is Proposition 13 popular today?

Is Proposition 13 still in effect?

Prop 13 explained

How did Proposition 13 change state power?

What is Prop 98?

What is the Prop 98 guarantee?

What is the Prop 98 maintenance factor?

What is Prop 98 funding?

What did California Proposition 30 do?

What funds are not in Prop 98?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

This lesson explains both initiatives, how they came to pass, and their impact on education today. Here's the short version: Prop 13 made public education state-funded; Prop 98 made education funding rise automatically as a function of state tax receipts.

How did Proposition 13 happen?

California's voters passed Proposition 13 in 1978, a time of enormous upheaval. The economy of the mid-'70s was reeling from a sudden increase in global oil prices driven by the creation of the OPEC oil cartel. America's economy had tipped into stagflation, a combination of slow growth and rising prices.

California home prices had climbed to levels never seen before. Homeowners, grappling with big increases in their property taxes driven by these higher prices, were frustrated and worried. Some found themselves "house rich" but unable to pay rising property tax bills.

Meanwhile, the laws governing local school districts were in a state of flux. Schools in California at the time were funded by local property taxes, levied as a percentage of each property's assessed market value at rates set by local school boards. In the landmark Serrano v Priest rulings, the California Supreme Court decided that this system violated the state constitution because differences in taxable wealth from one school community to another generated gross inequities in funding per student. As a remedy, the Court imposed a system of local revenue limits based on what local funding levels had been in 1972.

This change was meant to equalize funding in Robin Hood style. Over time, the court's plan was to redistribute local tax receipts that exceeded the limits. Understandably, this approach enraged those who stood to lose from it.

At the same time, the context for education finance was changing dramatically. Teacher union membership had expanded dramatically in the 1960s and early 1970s, and in 1975 collective bargaining for teachers became mandatory with passage of the Rodda Act, supported by a new Governor, Jerry Brown. Teacher pay rose with inflation, union power, a changing labor market that offered new professional options for educated women, and the radical idea of equal pay for equal work. School boards, trying to keep up with these forces and avoid strikes, began to find loopholes and levy new taxes that could not be redistributed.

What did Prop. 13 do?

The authors of Proposition 13 pitched it as a "taxpayers' revolt". Passed by a huge margin (64.8%), this popular initiative stripped local school boards and other entities of their authority to levy taxes. It dramatically lowered property taxes to a uniform 1% of assessed value, slammed the door on known loopholes, and presented existing homeowners with a nearly irresistible temptation: a permanent tax break. At the time, inflation was increasing prices at a rate of six or seven percent annually. Under Prop 13, the tax-relevant assessed value of a home is allowed to grow at only 2% per year unless sold.

In an attempt to prevent the state government from raising new taxes, voters enacted a policy known as the Gann limit in 1979, capping the amount that the state may legally spend. There have only been a few years when this was an issue, but illustrates the density of the legal thicket that surrounds California's education budget. This stuff is seriously complicated.

How did Prop. 13 make inequality worse in California?

Anyone person or business who owned property in 1978 received an immediate economic windfall from Prop 13. Over time, the windfall grew even larger. The market values of properties in California have increased dramatically, while the assessed values, upon which property taxes are based, have remained effectively frozen under Proposition 13. As property values rise faster than the 2% cap, the effective tax rate on property drops. The tax advantage has been even larger for higher-value property than for average property.

In 2022 the Opportunity Institute and Pivot Learning co-released a thorough analysis of the inequitable effects of Proposition 13, titled Unjust Legacies.

How Prop. 13 centralized power in Sacramento

With a single vote, Proposition 13 flipped the local and state roles in funding schools.

As discussed in Ed100 Lesson 8.3, with the passage of Prop 13, Sacramento suddenly became the center of the universe when it came to school funding in California. In most districts, property taxes at 1% of assessed value were not enough to cover the revenue limit requirements established in the Serrano settlement. To fill in for the lost funds, California quickly became a state with low property taxes and high state income taxes.

These changes were the starting point for a long decline in California's investment in public education relative to its history, its economy, and relative to other states and nations.

What is Proposition 98?

By 1988, many Californians had become alarmed at the state of their public schools. School construction had failed to keep pace with population growth, and existing schools were looking crowded and shabby. (See lesson 5.9 for more about facilities, and the role that ballot measures played in that story.) Class sizes were trending upward, and schools found themselves continuously making difficult cuts.

With Prop 13, voters had made Sacramento responsible for education funding - but Sacramento had other priorities. Education shrank as a percentage of the state budget even as the needs of the system were rising.

To force change, voters passed Proposition 98. This ballot measure, passed by a narrow margin, did not raise taxes or add new revenues to the budget. Rather, it amended the constitution to guarantee that a larger and more consistent fraction of the state budget be spent on education, specifically on K-12 education and community colleges (K-14 education).

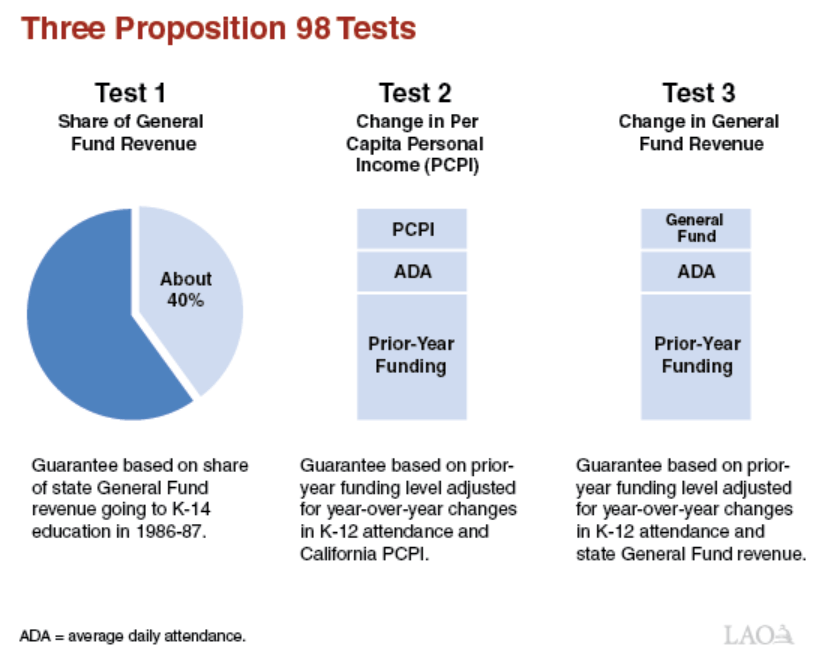

Of course, that's a massive oversimplification. Here's a slightly less simple one. The portion of the budget that should go toward K-14 education under Proposition 98 is:

- A set share of the state's General Fund (about 40%) OR at least the same amount as the previous year, adjusted for growth in student population and changes in personal income (whichever is larger), but

- When the state's revenue growth is low or negative, education will temporarily take its “fair share” of the hit, with the understanding that the money deferred is to be restored when state revenues rebound; and

- the legislature, with a two-thirds vote, can suspend the funding requirement under Proposition 98 in any single year.

Calculating the precise amount of the Prop 98 guarantee each year is complicated, and the stakes are high. The California Department of Finance is responsible for the math. Most education-related expenses are considered part of the Proposition 98 budget, but not all of them. Every year, a cottage industry of lawyers, consultants and advocates earns a living debating and explaining the interpretation of Proposition 98.

The process consumes a great deal of energy in the annual budget process. For a historical summary of the sequence of legislation that led to Prop 98, this paper by Virginia Alvarez is hard to beat.

It is unfortunate that Proposition 98 has caused California's leaders to fight budget battles on the grounds of legal details and formulas rather than on the real needs of students. (Kevin Gordon, a California policy consultant and expert on Prop 98, has even been heard to wonder aloud whether Prop. 98 has done more harm than good.) On the other hand, having a rule in place does support the idea that the conversation should involve real numbers.

What is the maintenance factor?

The Prop. 98 guarantee is particularly important — and challenging — when the budget is tight. California's constitution requires a balanced budget. During the Great Recession, to balance the budget the legislature diverted funds that were guaranteed to education under Prop. 98, creating a massive internal IOU. By 2011, the cumulative shortfall (known as a maintenance factor) between the real budget for education and the unachieved Prop 98 guarantee exceeded $12 billion — about $2,000 per student in a year when education spending per student was about $11,000. It was paid back over years, but in the lean budget of 2024-25 the state drew down its reserves to fund education and still had to create a maintenance factor.The shortfall in 2011 left an important legacy — it helped convince voters to temporarily raise taxes. Governor Jerry Brown turned to voters by putting Prop. 30 on the ballot. This measure, passed in 2012, asked for a temporary increase of about $6 billion in income and sales taxes to supplement the state's general fund. In 2018, voters extended an income tax on high earners through 2030.

Education funding in California shriveled as a lasting result of the Great Recession (December 2007 to June 2009). It took seven years for funding per student to return to pre-recession levels, adjusted for inflation. Education funding grew significantly thereafter, but generally only by the minimum required by Prop 98. As many observers have pointed out, the Prop98 guarantee can serve as a floor, but also as a ceiling.

In 2021-22, strong growth in the state economy and the stock market lifted California tax receipts to unprecedented levels. Proposition 98 ensured that school budgets increased, too, but state leaders broke precedent by going further. The state education budget for 2022-23 exceeded the Prop. 98 minimum by about $9 billion. The following years were not as bright, reflecting the zigzag path of the stock market and a bout of inflation, but Proposition 98 protected K-14 funding even in the disastrous budget of 2024-25.

This lesson was updated in July 2024.

Quiz×

CHAPTER 8:

…with Resources…

-

…with Resources…

Overview of Chapter 8 -

Education Spending

Does California Spend Enough on Education? -

Education Purchasing Power

What Can Education Dollars Buy? -

Who Pays for Schools?

Where California's Public School Funds Come From -

Prop 13 and Prop 98

Initiatives That Shaped California's Education System -

LCFF

The Formula That Controls Most School Funding -

Categorical Funds

Special Education and Other Exceptions -

School Funding

How Money Reaches the Classroom -

Do California Schools Waste Money?

Is Education Money Well Spent? -

More Money for Education

What Are the Options? -

Parcel Taxes

Only in California... -

School Volunteers

Stealth Wealth for Schools

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Jeff Camp - Founder June 15, 2023 at 5:07 pm

Carol Kocivar July 5, 2022 at 3:07 pm

How Proposition 13 Has Contributed to Intergenerational, Economic, and Racial Inequities in Schools and Communities

The Opportunity Institute and Pivot Learning

Key findings from the Unjust Legacy report about the impact of Prop. 13 include:

There is a widening housing wealth gap between Black and Latino Californians and white Californians, relative to their share of the Golden State’s population.

Prop. 13 offers a large tax subsidy to older and longer-tenured homeowners, homeowners with high-value properties, and for commercial property owners. This comes at the expense of newer home owners and city services.

Prop. 13 has contributed to a limited housing supply and to more costly housing.

Reforming Prop. 13 could increase revenues for public schools.

https://theopportunityinstitute.org/unjust-legacy-webinar-prop-13

Sonya Hendren June 29, 2020 at 7:45 pm

Jennifer B May 19, 2020 at 9:56 am

The Voter Guide for Proposition 111 (1990) can be reviewed directly on the UC Hastings Law Library site (https://repository.uchastings.edu/ca_ballot_props/1016/) and is summarized on Ballotpedia (https://www.ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_111,_Gasoline_Tax_Increase_(June_1990). The focus of the proposition was, as can be imagined, gas taxes and the Gann state spending limit. The effects on education funding received little specificity in the LAO analysis available to voters.

Jeff Camp July 15, 2019 at 1:06 am

jacquelinebispo May 2, 2018 at 6:09 am

Carol Kocivar August 7, 2017 at 10:49 am

http://www.lao.ca.gov/reports/2017/3526/review-prop-98-011817.pdf

jacquelinebispo May 2, 2018 at 6:02 am

Jeff Camp December 8, 2016 at 10:25 am

Steven N October 1, 2015 at 12:05 pm

jacquelinebispo May 2, 2018 at 6:16 am