Pay for teachers is different than in other work. Comparing can be tricky.

In This Lesson

What is a defined benefit pension?

What is a defined contribution pension?

How are teacher pensions different?

Why don't teachers get Social Security benefits?

How does a teacher's pension work?

What does 2% at 62 mean?

What does 2% at 60 mean?

Why did the teacher pension system change?

Why are pensions so complicated?

How do STRS and Social Security interact?

Who pays for teacher pensions?

Is the teacher pension system safe?

What is pension spiking?

How good is the California teacher pension system?

Do teacher pensions actually affect students?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

Teachers aren't lavishly paid, but it's easy to underestimate the true value of a teacher's total compensation. For full-career teachers in California, each year of teaching comes with a growing promise of a financially secure retirement. How much is the promise worth?

This lesson explains how teacher pension systems work, how they are different from Social Security, how to compare them with other retirement systems, why older teachers stop agonizing about retirement at age 62, and why younger teachers will agonize about it until they are 65.

Teacher pay is better than it looks

A teacher's total pay is better than it looks. (Unless something goes terribly wrong again, that is. It could. But we're getting ahead of ourselves.)

Teachers' pensions in most states, including California, are defined benefit systems. After retiring, teachers receive pension payments in a manner defined by the rules of the pension system.

Most workers pay into Social Security. California government workers pay into CALPERS. California teachers pay into STRS. (It's pronounced "stirs").While working, you pay the system. After you retire, the system pays you. How much? It depends. The amount you get out of a defined benefit system in retirement does not necessarily reflect the amount you pay in. Instead, the amount that the system pays out is determined by a formula.

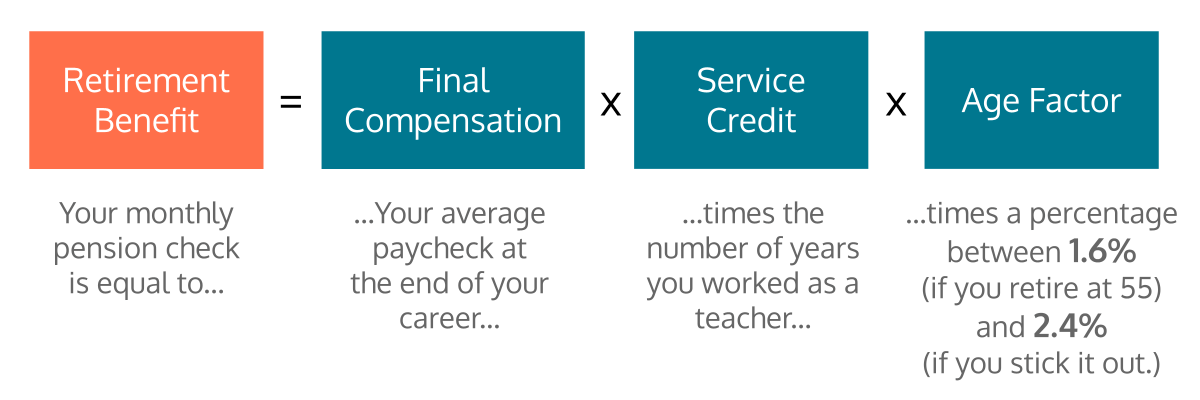

For public school teachers in California, the pension formula depends on just three things: Your end-of-career pay, the number of years you have been teaching in California public schools, and your age at retirement:

STRS is like Social Security for teachers. Sorta.

California's state pension system for teachers was created in 1918, long before Social Security was founded in 1935. In 1950, states were given the option to merge their pension systems for public employees into the Social Security system. Most did. California and 13 other states, in whole or in part, opted not to do so, instead maintaining separate retirement systems for public school teachers.

Teachers in California don't pay social security taxes on their paychecks or receive social security benefits. Instead, they pay into STRS, the State Teacher Retirement System. The acronym is treated as a name, pronounced “stirs”.

Superficially, STRS is similar to Social Security. In both systems, a portion of gross wages is withheld from each paycheck. Both systems make payments to members after retirement. In both systems, your age at retirement matters. You get more money if you defer retirement and retire later.

There are important differences, though. The Social Security system describes itself as an anti-poverty program. It doesn't differentiate the age at which you make your money, the kind of work you do, the state you live in, or the number of years you have worked in a particular profession.

These are central factors in the California STRS system because it has a different mission. It isn't an anti-poverty program. It's a system with a clear mission: provide a strong life-long pension for those who make it their life's work to teach in California's public schools. According to STRS, about half of California's teachers stay in the profession for at least 30 years.

How does California's teacher pension system work?

Public school teachers in California join the CALSTRS pension system automatically with their first paycheck. For as long as they work as a teacher in a California public school (pre-K through community college), a portion of gross pay (about 10.2%) is pulled out as a required contribution to the system. You can think of this as comparable to the 6.2% Social Security payroll tax that teachers don't pay on their salaries. In both systems, these contributions are generally not tax deductible.

After retirement, teachers stop receiving paychecks from their school district and start receiving payments from STRS, instead. (Confusingly, STRS calls these after-retirement payments benefits. It's easier and more accurate to think of them as income, as tax authorities do.)

Two systems:

2% at 60

2% at 62

California's teacher pension system has gone through significant changes over time in order to ensure that the system is financially sound, balancing contributions now with benefits later. Among the changes, the retirement terms for teachers were adjusted to make it a bit less attractive to retire early. For teachers hired after Jan 1, 2014, the system is described as 2% at 62 because those who retire at age 62 (generally) receive an annual retirement benefit for life equal to 2% of their final salary times the number of years served.

For teachers hired prior to Jan 1, 2014, the system is described as 2% at 60. The system is similar, but more generous — it offers full lifetime retirement benefits earlier. In both cases, the system strongly rewards teachers who delay retirement and continue teaching longer.

The chart below shows lifetime compensation for “Bee,” a hypothetical teacher who begins teaching in Oakland Unified School District in 2022 at age 29 (the STRS average age). Over time, she earns degrees that boost her pay. She retires at 65 (the pension-maximizing age), and lives to 91 (the STRS forecast average for female teachers. For men the average is 88.)

The point of a defined benefit pension is security. California public school teachers know they will receive predictable, ongoing money in retirement for as long as they live, even if the market swoons, and even if they are lucky enough to live a long time. As of 2024, there were 450 retired teachers in the California STRS system over the age of 100.

The chart above shows when teacher pension payments are paid out. It's worth understanding when they are earned.

Teachers qualify to receive a pension in retirement only if they work in the system for at least five years. Each service year thereafter affects the calculation of their annual pension in retirement. Teachers are eligible to retire at age 55, but the system is set up to encourage long service, especially from ages 56 to 65. Teachers qualify for a big portion of their lifetime pension in those years:

Using the same assumptions, the next chart puts it all together. For each year that Bee works, the chart below shows how much she earns in salary (teal), how much she pays into STRS (yellow), the incremental cumulative lifetime value of expected future pension payments (orange), and the one-time value of each pension payment she skips by continuing to work (grey).

What is the 2% at 60 system?

The teacher pension system works differently for teachers hired before Jan 1, 2014 than it does for those hired after that date. For those older teachers, the system is known as 2% at 60. There are several important differences.

| How are benefits different for older teachers under the "2% at 60" system? | |

|---|---|

| Earlier retirement. | Rather than at 65, teachers reach the maximum offered pension at age 63 — or as early as age 61½, if they have been working in the system for 30 years. |

| Fewer limits. | STRS members who qualify for the 2% at 60 system have access to some benefits that have been capped in the newer system. Some of these limits apply only to members with unusually high salaries. |

| Purchase of service credit. | Under limited circumstances, the STRS system (like other defined benefit systems) allows educators to purchase service years. When offered, the price differs between the two systems. |

| Huge pension incentive at 30 years. | As shown in the chart below, the 2% at 60 system includes an extraordinary perk, known as the career factor (or the longevity bonus) that further accelerates qualification for the maximum pension of 2.4% of final salary times each year of service. It's a single-year incentive approaching $300,000 in lifetime pension value. |

Why did California's teacher pension system change?

For decades, California's pension systems seemed magical. Oops.

Pension systems balance on a handful of critical assumptions. Will the number of working teachers increase? How many years will teachers work? How long will they live? How will prices change over time? Will invested assets grow in value? By how much and when? Will policies change?

For decades, California's pension systems seemed magical. California was growing, with young teachers joining in droves. Teachers were required to contribute just six percent of their wages toward their retirement system, but the math worked! STRS had amassed a big investment fund, and it was delivering remarkable earnings, especially from tech investments. In the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, California's public pension systems appeared to be overfunded, so the legislature generously changed the math to create the 2% at 60 system, lowering retirement age requirements and raising benefits.

Big mistake. On cue, the boom went bust.

The pension system relies on ongoing support from taxes

The charts above probably seem out of balance, right? How can such small contributions (the small yellow bars at the bottom) balance the large pension payments represented by the orange bars?

They can't. The STRS system relies on money from four sources:

- Income generated by the STRS investment portfolio;

- Contributions required from teachers;

- Contributions required from employers (e.g. school districts); and (when all else fails, which it does)

- Money from the state budget.

There's no free lunch here. Money that school districts must spend on pensions for retired teachers is money they cannot spend on other priorities — including educating today's students.

For two decades after the tech bust, even as the stock market grew, the STRS investment portfolio fell behind, gradually losing its capacity to reliably sustain the state's obligations to teachers. The funded ratio of the STRS account withered from better than 100% funded to about two-thirds funded. Financial experts (actuaries) warned that, without action, the fund would be depleted by 2046. A pension fund can weather bad years if it is healthy. An unhealthy pension fund is a time bomb, just waiting for the next bad year to turn into a disaster.

As one of his final acts in office, in 2015 Governor Jerry Brown pushed through a 32-year plan to defuse the pension time bomb. The plan clarified the state's commitment to serve as the funder of last resort, but in exchange it required higher contributions from both teachers and school districts. The plan was initially expected to bring the system to full funding by 2046. As of 2024, better than expected market returns were forecast to deliver full funding in 2043, three years ahead of plan.

Higher state and local contributions can improve the financial health of the teacher pension system, which is great. But the money isn't coming from a magic well — it's mostly coming from school district budgets.

The legislature broke the teacher pension system in the dot-com era

If you hear that the state budget is going up, but your school is making cuts, now you know a big part of the reason why: the legislature broke the teacher pension system in the dot-com era, let it stay broken for two decades, and now the bill is past due.

This video from EdSource.org does a great job of summarizing the issues.

Pension funds are invested in many long-term assets that are illiquid, meaning they can't be easily sold or valued. By far, most of the value of the fund has come from investment gains.

To safely weather bad years, defined-benefit pension funds need to be enormous. With assets estimated at about $344 billion, the CalSTRS fund is the biggest of its kind in America.

The CALSTRS fund is managed by professional staff and overseen by a Board of Directors that consists of a mix of elected officials, retired teachers, and appointed members. Every few years, the board releases an official estimate of the current value of the assets, along with a long-term view of where the money came from. Many of the investments are illiquid, which means they are long-term and can't efficiently be sold to make pension payments.

Why are pension systems so complicated?

Pension systems need sophisticated rules because reality is complicated. What if a teacher is called to military service? What if a teacher needs to take time out for cancer treatments? What happens if a teacher is accepted for an overseas fellowship? What if a teacher's district wants to offer an incentive for a teacher to retire early?

To address issues like these, the system has to embrace complexity. In 2024, CALSTRS employed roughly 1,300 people to support a system of over a million educators, about half of them active. The following video explains some of the challenges, such as systemic vulnerability to abuses like spiking, in which teachers or employers exaggerate end-of-service payments to claim higher pay in retirement.

What if teachers also earn Social Security wages?

Interaction with the Social Security system is a good example of why a big pension system needs sophisticated rules. In the course of their career, many teachers have other jobs. A person who works part of a career in STRS employment and part of a career in "regular" employment, paying Social Security taxes, may qualify for retirement benefits from both systems.

There's a wrinkle. As described above, the STRS formula strongly rewards lots of years of service and high end-of-career earnings. The Social Security system is set up in a roughly opposite way; it is progressively indexed to provide extra support to those with low total earnings. If you pay in only a small amount to Social Security, the system assumes that you are poor and need more support.

To prevent abuse of this progressive indexing, Congress passed laws in 1977 (the Government Pension Offset, or GPO) and in 1983 (the Windfall Elimination Provision, or WEP). These provisions were good tax policy but bad politics. Teachers unions steadily lobbied to eliminate them, and in 2025 they achieved their goal: Both provisions were repealed by the Social Security Fairness Act (H.R. 82), which President Biden signed into law on January 5, 2025. About 3.1 million retired teachers who had also worked in non-STRS jobs received a total of $17 billion from the Social Security system. In politics, persistence pays.

Are teachers' pensions safe?

Risk is a central concern for any retirement system. Is there enough invested to weather bad financial conditions? With the changes made in 2014, California's teacher retirement system reversed its death spiral. It now appears to be on a long, slow path to sustainability.

California's STRS system is huge, and it is far from the only one. In 2023, the US Census Bureau estimated that there were 304 state-level pension systems for public employees and 4,632 local systems. Collectively, these systems manage the investment of trillions of dollars in pension savings. In 2025, the US Census Bureau estimated the total assets under management of just the 100 biggest at about $5 trillion.

Many of the scenarios that keep economists and bankers up at night involve collective risk. Adverse market conditions don't just affect one pension system at a time — in a truly awful downturn, many public pension systems would be stressed simultaneously. Some would not make it. The Social Security system looms large in conversations about the financial risks of retirement insurance systems. Actuaries warn that the system has been out of balance since 2010. According to the 2024 annual report of the trustees of board the Social Security system, "Social Security is not sustainable over the long term at current benefit and tax rates. …the trust fund reserves will be depleted by 2035."

Some argue that big defined-benefit public pension systems have become unacceptably risky in a world where people live longer and have fewer children. The systems were created under conditions where there were more "actives" contributing to the system than "beneficiaries" drawing from it, and those conditions are steadily changing. They advocate for a different approach.

What is a defined contribution pension system?

The biggest, scariest "fix" for the teacher pension system would be to abandon it in favor of a defined contribution system, the structure overwhelmingly used in the private sector.

In a pure defined contribution system, there is no central retirement fund, and no pension formula. Instead, individuals are responsible for saving and investing in their own retirement. Usually, employers encourage employees to invest for retirement by matching the funds they commit to their retirement account, with the requirement that money not be withdrawn until retirement. These retirement savings accounts are allowed to grow tax-free until withdrawn at a specified age.

In the private sector, this kind of savings instrument is called an IRA or 401(k) account. Similar savings accounts exist to help educators save for retirement — they are known with names like 403(b), 457(b), Roth 403(b), and Roth 457(b). In California, teachers can use these accounts to save for retirement on top of their STRS pension. Some states, including Florida, Alaska, Washington, and Kansas have transitioned away from defined benefit systems for teachers, making these saving accounts the primary retirement security system for teachers.

For arguments in favor of the defined-benefit approach that California has now, read the analysis of the Berkeley Labor Center. For arguments in favor of shifting to defined-benefit models visit teacherpensions.org. And yes, of course there are in-between solutions, like the cash balance (CB) model used in Florida.

Does California have a good teacher pension system?

Well, that depends on how you define "good." Pension systems serve different stakeholders differently. California's system works mainly to the advantage of full-career teachers, especially those that start young, earn lots of graduate credits, and retire at the optimal age. In a 2021 review of state teacher pension systems, Bellwether Partners ranked California's system among the ten worst in America.

The STRS system in California strongly benefits teachers who work in the same school district for a full career. It is less beneficial for those who change school districts, and a truly raw deal for those with less than five years of service. With the repeal of windfall elimination, advocates for retirement fairness can also argue that California's teacher retirement system takes unfair advantage of the Social Security system, making its sustainability worse.

Do teacher pensions actually affect students?

An out-of-balance pension system can seem like an abstraction, but it matters a lot. The California STRS pension system went from fully funded to dangerously out of whack in about two decades. Putting it back on a path to sustainability is diverting huge sums from school budgets, and the damage will be felt for decades. The money it is taking to rebalance the pension system is crowding out spending on students, teachers and schools. A 2018 analysis by WestEd argued that the combination of these factors is equivalent to a Silent Recession.

This post concludes the "Teachers" chapter of Ed100. The overall structure of Ed100 is "Education is Students and Teachers spending Time in Places for Learning with the Right Stuff in a System with Resources for Success. So Now What?"

In the next chapter, we tackle the educational implications of life's most precious resource: Time.

References: Ed100 pension model, CalSTRS Retirement Calculator, CalSTRS Member Handbook.

Updated September 2025.

Quiz×

CHAPTER 3:

Teachers

-

Teachers

Overview of Chapter 3 -

Teacher Recruitment

Who Teaches, and Why? -

Teacher Certification

How Are Teachers Prepared? -

Teacher Retention

How to Keep a Teacher -

Teacher Placement

Who Teaches Where? -

Teacher Development

How Do Teachers Improve? -

Teacher Collaboration

How do Educators Work Together? -

Teacher Benefits

Healthcare and Sick Days -

Teacher Pay

How much are teachers paid? -

Teacher Evaluation

How Do Teachers Know If They Are Succeeding? -

Tenure and Seniority

Teacher Tenure - Good? Evil? -

Pensions

How Good is a Teacher's Pension?

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Lulu Mavi September 18, 2024 at 8:56 pm

Heather L Ippolito August 13, 2024 at 2:42 pm

Maria Rivera February 16, 2024 at 1:42 am

norburypta October 30, 2023 at 12:56 pm

Carol Kocivar June 14, 2022 at 12:59 pm

Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature consider the following changes: (1) allow CalSTRS to increase the state’s contribution rate by more than is currently allowed; (2) eliminate the complex theoretical calculations currently used to determine assets and obligations assigned to the state and employers in favor of a fixed proportional division of UAO; and (3) make the provisions of the funding plan ongoing, allowing CalSTRS to develop an amortization policy to address future losses in line with industry best practices.

https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Report/4400#LAO_Comments_and_Recommendations

Carol Kocivar June 5, 2022 at 5:51 pm

"The high cost of the pension system is due to chronic underfunding, not lavish benefits for teachers. In fact, CalSTRS provides most of California’s teachers with a low-quality benefit. Only 72 percent will vest and qualify for a pension at all. In the end, only 33 percent of teachers serve in California’s schools until they reach normal retirement age. And since the state does not participate in Social Security for educators, those teachers who leave the profession or move to a new state are in worse shape financially than they would otherwise be."

https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55f70367e4b0974cf2b82009/t/6226b50e84747636bf106df6/1646703893640/California+Pension+Brief+Final.pdf

Carol Kocivar June 5, 2022 at 3:45 pm

Traditional pensions fail to justly compensate a large portion of teachers for their work every year in the classroom. They’re often massively expensive and incredibly complicated. Over the past decade, retiree benefits have been in flux. But all is not lost. Policymakers have options that can make retirement more fiscally sustainable and fairer to a next generation of teachers. It’ll take much hard work, but kicking the can down the road is a short-sighted option.

https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/can-states-clean-their-teacher-pension-messes

Jeff Camp - Founder April 23, 2022 at 1:10 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder September 30, 2021 at 10:53 pm

John Buck January 15, 2019 at 12:20 pm

Jeff Camp January 15, 2019 at 12:56 pm

June 20, 2018 at 5:42 am

Jeff Camp June 20, 2018 at 11:39 am

Carol Kocivar May 28, 2018 at 10:41 am

Read the

Carol Kocivar May 28, 2018 at 10:42 am

Jeff Camp - Founder April 15, 2018 at 5:24 pm

MaryGW April 3, 2018 at 9:55 am

Jeff Camp - Founder July 31, 2017 at 2:20 pm

Jeff Camp February 3, 2017 at 2:31 pm

Albert Stroberg May 1, 2016 at 6:58 pm

Manuel RomeroNickname June 27, 2015 at 12:09 pm