Teachers substantially work alone most of the time. How can anyone tell whether they are good at what they do?

In This Lesson

How are teachers evaluated in California?

What does a teacher evaluation look like?

Are teacher evaluations based on results?

How do different states evaluate teachers?

Should test scores be used to evaluate teachers?

What is the Stull Act?

What is Peer Review in schools?

How can we get rid of a bad teacher?

How can students contribute to a teacher's evaluation?

What is "Value Added" evaluation in education?

How can teachers get useful feedback?

What is the purpose of teacher evaluation?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

The heart of improvement is to do more of what works, less of what doesn't… and know the difference. Knowing the difference requires meaningful evaluation, which is rare in California's public education system. This lesson explains how teacher evaluation systems work (or don't) in California schools, and explores what schools and districts can do about it.

Evaluation is uncomfortable

First, some honesty: Does anybody really like being graded? Students have to tolerate a lot of evaluation. Teachers don't. When teachers are evaluated, it can feel random, intrusive or threatening.

How are teachers evaluated?

California law requires schools to periodically "evaluate and assess" teachers, but teachers rarely receive feedback of value. Most teachers, by far, receive a passing evaluation, even in schools where lots of students are far behind. In a typical school, the principal or a designated evaluator walks by with a clipboard at least once every five years, watches from the back of the room for a few minutes, makes a few marks on a form, and leaves. During the Pandemic, many schools dispensed with even this pretense.

Overall, about 84% of teachers in California public schools receive a summary evaluation of clear. About 4.6% are evaluated as ineffective, with variations by subject matter.

Except for new teachers, extensive observation tends to be a sign of trouble. Sometimes administrators use the discomfort of being observed as a pressure tactic to spur teachers to leave a school, or even to quit. To head off this practice, some teacher contracts limit the number of times a principal may observe a teacher, or set rules that require the principal to provide advance notice for observation.

Many states require teachers' evaluations to include students' results. Not California.

Over the last two decades or so, most states have evolved their expectations about how teachers should be evaluated. In California, very little has changed. Why? Some background is important.

Constitutionally, public education is the responsibility of the state, but effective schools are in the national interest for all kinds of reasons. With bipartisan support, the federal government has played a key role in prodding states to implement important changes such as setting and aligning educational standards, providing special education, and shining light on achievement gaps through universal testing. The minimum qualifications for teachers are now a matter of state law, but during the No Child Left Behind era under the Bush and Obama administrations, federal law established the expectation that teachers should be highly qualified.

In 2009, the New Teacher Project, a non-profit organization, released a withering critique of teacher quality in America under the title The Widget Effect. The report argued that “school systems treat all teachers as interchangeable parts, not professionals. Excellence goes unrecognized and poor performance goes unaddressed. This indifference to performance disrespects teachers and gambles with students’ lives.”

The report was hugely influential, partly due to timing. The US economy had slipped into a steep recession (the "Great Recession") at the end of the Bush administration in 2007. School districts were laying off teachers, and parents were upset to see young teachers given the boot regardless of their effectiveness. Congress allocated billions for a recovery plan, including funds to reduce the damage inflicted on public education. The Obama Administration invited states to use the moment of crisis to overhaul educational standards and other policies.

A federal grant program called Race to the Top offered states a competitive funding incentive to adopt policy changes from a menu of options. One key option: change the approach to teacher evaluations so that they would be partly based on multiple sources of evidence, including improvement (growth) in test scores among the students they directly teach. California's teacher unions broadly opposed evaluation of teachers — and still do in practice, albeit not in theory. (See the latest CTA policy for more nuance.) When Jerry Brown became Governor in 2012, he withdrew California from consideration for the grant.

In California, test scores may not be used as a factor in teacher evaluations unless collectively bargained otherwise. It doesn't happen.

In 2015 an education advocacy group in California backed a lawsuit (Doe v. Antioch et. al.) to push the issue. Pointing out that California law (the Stull Act) obligates school districts to evaluate teacher performance, they argued that scores on tests based on the state's standards should be part of the evaluation. The lawsuit failed to achieve its purpose. In 2016 Superior Court judge Barry Goode ruled that the Stull Act requires some kind of evaluation, but leaves the manner and consequences of evaluation up to school districts. Nothing changed.

How states other than California evaluate teachers

The National Center for Teacher Quality (NCTQ) is a non-profit organization that tracks policies about teacher evaluation as part of its work. Every few years, the organization summarizes policies in this area, state by state. According to NCTQ, as of 2022 most states don't require their school districts to evaluate teachers in any particular way. It's left to local school districts.

Many states do, however, set some rules to guide districts about how to evaluate teachers if they choose to do so. For example, about half of states require districts to measure growth in student achievement if they choose to evaluate teachers in a way that involves test scores. In practice, this requires school districts to have a fairly strong data system that can associate teachers with their individual students' scores over at least two years. Additional teacher evaluation elements can come from peers, students, self-evaluation, administrators, or other sources.

Under the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), states were required to have a policy regarding how teachers ought to be evaluated. In 2015, with passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), the requirement went away. Teacher evaluation policies have become much more local.

As discussed in Ed100 Lesson 3.5, most school districts spend a lot of money on salary incentives for teachers to earn additional college credits. It's common to bring faculty together for ongoing training. Are the professional development programs they provide effective? The only way to know would be through evaluation.

Many pioneering schools and districts have taken inspiration from Charlotte Danielson's Professional Practice framework, which defines a rubric (scorecard) for evaluating and coaching teachers in order to make evaluations more consistent, focused, and purposeful.

Perhaps the most battle-tested system for teacher evaluation and improvement is in Washington, D.C., which has changed its approach many times over the years.

Should teachers review each other?

Teacher evaluations in California are conducted by their supervisors — usually principals. An alternative approach, called Peer Assistance and Review (PAR) involves teachers in the process. In this system, districts invest in more frequent observation and evaluation, and try to make the process beneficial for the teachers being observed. Underperforming teachers are assigned a coach and evaluated by a teacher panel.

There is some evidence that this approach is effective in raising teacher performance. It also may be helpful in “coaching out” some teachers who might do better in a different line of work. If managed carefully, PAR can help provide the required documentation to support a formal dismissal when called for. Critics of PAR express concerns that peers can be biased, and that the process can be demeaning.

In California, few districts have implemented PAR or other systems of constructive evaluation for teachers in part because they take time, and teacher time costs money. When it's time to negotiate a contract, most teacher unions have preferred to prioritize funding for salaries over funding for evaluation processes.

Why not ask the students?

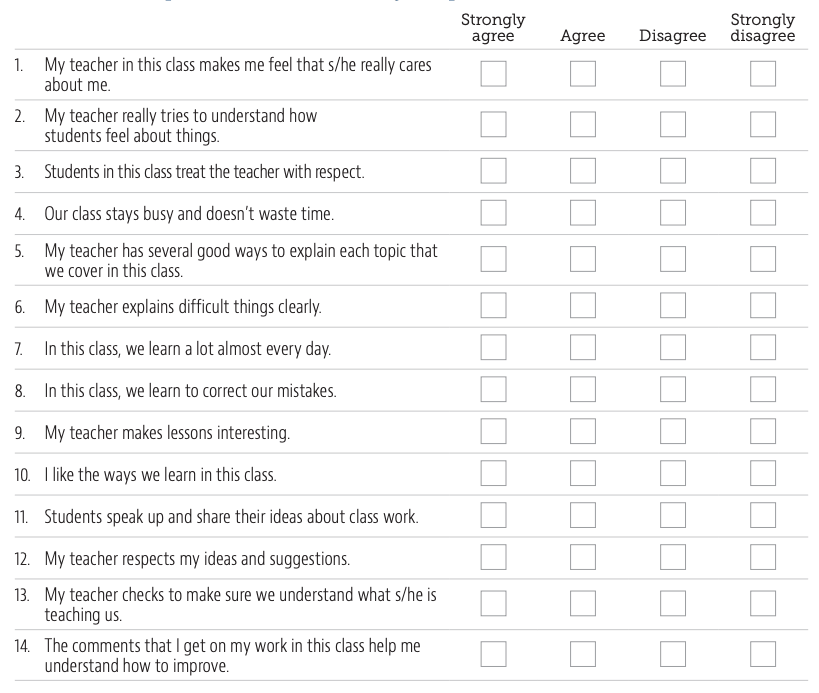

In 2013 the Gates Foundation released the final report of a massive three-year research effort called the Measures of Effective Teaching project (MET). Among the findings, the study validated what ought to be obvious: The people in a school who are best-positioned to know a teacher's strengths and weaknesses are the ones carrying backpacks: the students. A key conclusion of the MET project is that the most meaningful and useful way to evaluate teachers is to use multiple measures, including well-crafted student surveys.

“Students know an effective classroom when they experience one. That survey results predict student learning also suggests surveys may provide outcome-related results in grades and subjects for which no standardized assessments of student learning are available.

Further, the MET project finds student surveys produce more consistent results than classroom observations or achievement gain measures… Even a high-quality observation system entails at most a handful of classroom visits, while student surveys aggregate the impressions of many individuals who’ve spent many hours with a teacher.

Student surveys also can provide feedback for improvement. Teachers want to know if their students feel sufficiently challenged, engaged, and comfortable asking them for help. Whereas annual measures of student achievement gains provide little information for improvement (and generally too late to do much about it), student surveys can be administered early enough in the year to tell teachers where they need to focus so that their current students may benefit. As feedback tools, surveys can be powerful complements to other instruments.”

The evaluation surveys that the MET project identified as effective were developed by Tripod, which has continued to evolve and improve them.

The 2010 National Teacher of the Year, Sarah Brown Wessling, didn't wait for a grand edict from on high to survey her students. Inspired by a version of the Tripod survey (see image below), she created her own questions, including space for her students to write their own response.

California teachers can "opt out" of being evaluated by students.

In 2010 the California Association of Student Councils (CASC), a statewide organization of student leaders, successfully advocated for a bill that it thought would promote student feedback in teacher evaluation. Ironically, the legislation did the opposite. It explicitly allows what was already legal (teachers surveying their own students for feedback) but prohibits districts from systematically using student evaluations in meaningful ways. This is a good example of how well-intentioned policies can backfire.

What is Value Added evaluation in education?

Value added analysis is a statistical method used to evaluate the likely significance of various factors in producing an outcome. This kind of analysis is powerful because it can help focus attention on individual performance and cut through the "noise" of things beyond control. It is used in everything from finance to baseball. If you've seen the movie Moneyball, you've seen a version of it in action.

In analysis of education, the outcomes of interest are things like test scores, attendance, grades or graduation. Input factors that might have predictive power in such a model can include things like family wealth, community conditions, school programs and, importantly, the teacher. Given enough data, a value-added analysis can statistically suggest which specific teachers are consistently associated with desirable results, even in a sea of undesirable results. Value-added analysis statistically examines whether students are scoring as expected, given their circumstances, or differently.

Over time, if a teacher's students tend to come out of their classes with more improvement in their scores than the model predicts, the teacher might be doing something worth celebrating. Of course, the reverse is also true.

Methodologies for value-added analysis of education have improved over time, and there is a lot to know. Harvard Professor Raj Chetty studies this topic, and his explanations are useful.

What should be done about "bad" teachers?

The demand for meaningful teacher evaluation systems gained urgency during the Great Recession. Why? Because school communities wanted a better answer for a tough question: when the budget requires laying off teachers, who should be the first to go?

The lack of effective teacher evaluation systems made it difficult for school leaders to argue effectively that they should be able to use judgment in these decisions. Professor Eric Hanushek, who strenuously promotes the idea of more judgment in teacher retention, argues that targeted layoffs should be a key strategy for school improvement:

“If you eliminate the bottom five percent of teachers in terms of effectiveness, or if you replaced five to eight percent of the worst teachers with an average teacher, U.S. achievement would rise to somewhere between Canada and Finland. A small number of teachers has a really big impact on the achievement of kids.”

In 2013, the PACE/Rossier survey of California voters found that there is a widespread consensus that removing “bad teachers” would be a powerful lever for improving schools — more powerful than increasing funding, increasing overall pay, or offering teachers pay incentives. It was the top choice among every segment surveyed, including (narrowly) among teachers.

Voters, parents and teachers tend to agree that the system fails to take action when teachers are ineffective, and that inaction harms kids. This became one of the core arguments in an important unsuccessful 2014 court case, Vergara v. California.

Teachers in California enjoy considerable due process protections from dismissal. The topics of tenure and seniority will be the focus of Ed100 Lesson 3.10, the next lesson in this chapter.

A positive view of evaluation for teachers

How can anyone become better at their work in the absence of meaningful feedback?

In the vast number of cases, teacher evaluation is a positive thing. After all, how can anyone become better at their work in the absence of meaningful feedback?

Teachers don't necessarily reject evaluation — many embrace opportunities to improve. Greatness By Design, a California task force report developed with considerable teacher involvement, stresses that educators should be evaluated against professional standards and that evaluation should be informed by data from a variety of sources, including measures of educator practice and student learning and growth.

A positive view of teacher evaluation is a unifying theme of the TED Talk below, which involves notables John Legend, Ken Robinson, Bill Gates and many others.

This lesson was last updated in November 2023.

Quiz×

CHAPTER 3:

Teachers

-

Teachers

Overview of Chapter 3 -

Teacher Recruitment

Who Teaches, and Why? -

Teacher Certification

How Are Teachers Prepared? -

Teacher Retention

How to Keep a Teacher -

Teacher Placement

Who Teaches Where? -

Teacher Development

How Do Teachers Improve? -

Teacher Collaboration

How do Educators Work Together? -

Teacher Benefits

Healthcare and Sick Days -

Teacher Pay

How much are teachers paid? -

Teacher Evaluation

How Do Teachers Know If They Are Succeeding? -

Tenure and Seniority

Teacher Tenure - Good? Evil? -

Pensions

How Good is a Teacher's Pension?

Related

-

Student Leadership

Student Voice in Schools -

Teacher Development

How Do Teachers Improve? -

Teacher Pay

How much are teachers paid? -

Tenure and Seniority

Teacher Tenure - Good? Evil? -

Principals and Superintendents

The Pivotal Role of an Educational Leader -

The Federal Government and Education

Small money, Big Influence

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Blanca Serrano November 1, 2024 at 7:14 pm

Lulu Mavi September 18, 2024 at 8:43 pm

Rida Rfaqat August 21, 2024 at 9:28 am

Jeff Camp - Founder August 21, 2024 at 10:56 pm

David Scott May 1, 2024 at 10:31 am

Jeff Camp - Founder May 1, 2024 at 1:56 pm

LeeAnn Corral March 2, 2024 at 8:08 am

Maria Rivera February 16, 2024 at 1:29 am

Carolina Rufino February 16, 2024 at 1:01 am

Jenny Greene July 7, 2020 at 7:59 am

itgeek February 21, 2019 at 5:39 pm

Susannah Baxendale January 14, 2019 at 11:24 am

Carol Kocivar May 28, 2018 at 2:15 pm

Read the Report "

Albert Stroberg May 1, 2016 at 6:41 pm

Profs at the UC need student input as part of the promotion process- why not HS teachers?

Mark MacVicar July 8, 2015 at 9:14 pm

Liz Fischer June 30, 2015 at 9:53 am

In "A Practical Guide to Mentoring, Coaching, and Peer Networking: Teacher Professional Development in Schools and Colleges" by Christopher Rhodes, Michael Stokes, et. al. studies are sited that show teacher collaboration increases teacher empowerment, self-esteem and ownership of results. However, it's important to note that in order for such collaborations to work teachers need to have the personal and interpersonal skills to treat each other well so as to develop mutual trust, confidence and respect (West-Burnham and O'Sullivan,1998).

I think we don't just like good teachers, good teachers are likeable. Maybe student/parent surveys can help administrators to identify those teachers who can be the leader assets that "raise the tide" for their schools.

Stacey W April 6, 2015 at 7:15 pm

We should all be on the same team - with parents and teachers working together to offer the best educational experience and learning environment for our children. In the case of a really bad teacher (we've had one), I would think that if numerous parents had concerns about a teacher, then perhaps it would deserve some research by the school district and teachers' union.

Veli Waller April 5, 2015 at 10:11 am

Mamabear March 19, 2015 at 11:30 pm

Paul Muench November 8, 2014 at 12:20 pm