Imagine if Amazon couldn't keep track of customer purchases. Imagine a pharmaceutical company unable to tell one pill from another. Or a bank losing track of accounts.

In This Lesson

Why is education data important?

Why is California's school data system weak?

Why is education data so delayed?

How does California’s education data system compare?

How is education data useful?

What data does California collect about students?

How can I see data about my school?

What is a School Accountability Report Card (SARC)?

Why can't the state collect more data?

What data is included in the LCAP?

What is a School Plan for Student Achievement (SPSA)?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

The world has become accustomed to the idea that big organizations — including government organizations — should be good at using data. The education system has made slow progress in that regard, partly because it depends on coordination among decentralized organizations. In 2025 the challenge became harder with massive cuts to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the federal agency tasked with guiding data-related processes for the nation's education systems.

America's public data tangle

Accounting is detailed work. Business organizations pay top dollar for employees with the skills needed to maintain orderly financial records and processes across far-flung locations. Errors can be expensive, so businesses tend to centralize their systems and audit them regularly. Most public companies assemble figures from all over the world every month or more, summarize results quarterly, and issue a full report annually.

Local and state government systems face many of the same challenges as businesses, but they tend to be much less consolidated. In California alone, there are over 1,000 school districts, each with a significant amount of sovereignty over how it operates. Under the supervision of county offices of education, school districts have some practical reasons to follow accepted accounting practices so that they receive funds in a timely way, but there's a looseness to it all. Giant school districts have accounting needs that warrant complex systems. Tiny, rural districts can't afford them.

To understand the overall condition of local and state education in America, the US Department of Education suggests accounting practices, but it lacks the authority to enforce them or to command data delivery on a timeline. Even seemingly-simple questions like "how many teachers are employed by your district" can be hard to answer. Districts don't have a big incentive to spend time and energy conforming to national data standards, and many don't.

Comparable education data take years to arrive. It could get worse.

Every year, state and local leaders would like to be able to say how their schools currently compare to schools in other states. They can't. At its best in 2024, it took the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) about three years to release data it had collected from federal, state and local sources. These sources tend to be messy, and NCES took time and effort to assess and correct them. When the "latest numbers" were released in the national Condition of Education report, required by law, they were always out of step with current conditions. Try searching Google for information about how your state ranks in something simple, like education expenditures per student. You won't get a straight answer based on recent data.

In early 2025, the Trump administration complicated the challenge by withholding funds for the collection and analysis of education data. Release of the most essential data shifted to a rolling basis.

California’s state data tangle

California is revamping its education data systems.

When it comes to education data, California is at last taking steps to invest in new data systems. There’s a lot to make up for.

In the 2010's, the national Data Quality Campaign (DQC) regularly evaluated state-level education data systems. In 2012, it awarded California a low rating for the quality of its education data. The following year, California "addressed" this low ranking... by declining to participate in the survey. Then-Governor Jerry Brown, a declared skeptic of the value of education data systems, consistently opposed, blocked, or defunded many efforts to build or improve the quality and availability of education data, preferring to leave the matter to individual school districts.

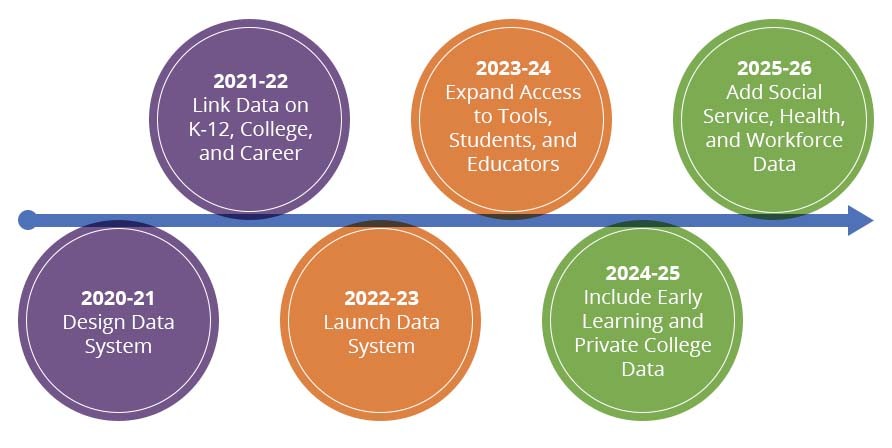

In 2021, Governor Newsom signed a bill into law to create a new education data collection system for California. This data system, poetically named P-20W, brings together data from early childhood, K-12, postsecondary, and the workforce (thus the W), all to better inform educators, parents, and students. This legislation builds off the Cradle-to-Career Data Systems Act, which had set out requirements for the creation of a new statewide data collection system. These pieces of legislation are important because they are making data more accessible as well as making it easier for students and families to plan the road to college and beyond. Implementation started in 2024.

Why data matters

The potential usefulness of education data systems is enormous — not just for analysis at the state level, but for practical use in the operation of schools and districts. Education data systems can enable students, parents, teachers, and school leaders to see assignments, get access to course materials, view grades, collect feedback and improve communication. Attendance systems connected to community services can help support attendance. Data systems can support research, shedding light on the effectiveness of educational materials. Data can help to identify extraordinary schools, teachers, and programs. But only if the systems are set up to collect and connect.

As described in Lesson 6.6, teachers and schools have become increasingly reliant on Learning Management Systems (LMS). These digital systems help teachers and students communicate about assignments, deadlines, and coursework. One popular LMS, Google Classroom, is free, but it has LMS competitors including Canvas, Schoology, and Moodle. It is inconvenient for students and teachers to use multiple systems, so there is natural pressure for schools and districts to coordinate their choices.

GreatSchools.org provided a State-by-State Assessment of Educational Data Transparency in 2019 by compiling research and data into one report. California's overall score was 1.7 (out of four) because of the large amounts of unavailable and nonexistent data on student growth and college enrollment, persistence, and remediation.

After the pandemic, the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) released a report in 2024 which graded all 50 US states on the level of transparency in their state websites, especially regarding the effects of COVID-19 on academic performance. California underperformed on this metric as well, receiving a D on an A-F scale.

This graphic shows the state's plans to implement its new education data infrastructure by the 2025-26 school year.

This graphic shows the state's plans to implement its new education data infrastructure by the 2025-26 school year.

When it comes to education data, California is changing the game.

The DQC hasn't been the only critic of the weaknesses of California's data systems for education. For example, a 2013 report from the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) echoed many of the same themes, as did a 2017 publication from the Education Insight Center titled California's Maze of Student Information. A 2024 article by EdSource touched on many of these same themes, as underfunding continued to impede access to relevant and reliable educational data.

One of California's major data systems for education is the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System, commonly known as CALPADS. The core element of CALPADS is a unique identifier for each student that remains consistent even as the student advances through grades (Pre-K through 12) and moves from one school to the next. The system also connects to some out-of school programs that receive federal funding, and to student enrollment data in state colleges.

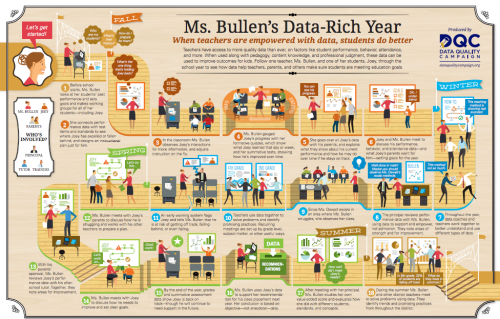

This infographic from the Data Quality Campaign describes some ways data can support teaching and learning. A related infographic emphasizes the value of data for school leaders.

This infographic from the Data Quality Campaign describes some ways data can support teaching and learning. A related infographic emphasizes the value of data for school leaders.Districts struggle to make sense of their data

Previous efforts to create linked data systems across sectors have been attempted in California, thanks to local effort. Doing this work, however, requires that local districts assemble (and pay for) their own data systems. These systems don't communicate well. When data moves, it's usually with a lot of trouble and delay. When we need answers for Ed100, it can be worse than finding a needle in a haystack, because it isn't even clear which haystack to look in.

SARCs. School Accountability Report Cards (SARCs) demonstrate the deep limitations of California’s data approach. This report, published by school districts, is meant to satisfy both state and federal requirements for public access to information about each school. Some of the data in the report comes from the State Department of Education. Other information must come from the school district, and some information can only come from the school. Districts are required to publish these reports annually, but not to a consistent location. They are also not required to retain them. Presumably, the content of a SARC should be of keen interest to the Schoolsite Council of each school.

The State provides a sample template for the SARC; school districts have the choice of using it, creating their own, or contracting with an outside vendor. School districts can use whatever approach they wish to make SARCs available to the public, but must also include a link on their website and submit the SARC to the state Department of Education. The result is a separate PDF file for each school each year. The state does not audit or summarize the data from this field of digital haystacks. Determined researchers can bring their own pitchfork to the job by visiting SARConline, where some schools have voluntarily posted their reports.

LCAPs. Since 2014, districts and charter schools have been required to create a document known as the Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP). Each year, each district is expected to use the LCAP to "tell its local story." The LCAP template requires specific kinds of information — but as with the SARC, the end result is a haystack of PDF files, often with multiple versions. The template does not "expose" data digitally, in a way that would make it easy to use. For example, to compare data from one district’s LCAP to another would involve manually copying it into a spreadsheet. Although the data included in LCAPs ought to be consistent with the data in SARCs, there is no mechanism to facilitate or enforce this consistency.

SPSAs.The LCAP, in principle, is meant to align with the information in SARCs as well as with each school's separate School Plan for Student Achievement, yet another document required under state law.

In an effort to be thorough, and to comply with state and federal requirements, these documents go on for pages and pages. While thorough, these documents are often difficult to understand or use.

Mandates

Using data systems in consistent ways could make accountability reporting more accessible to the public, more straightforward for districts, and more transparent in general. But that kind of data infrastructure coordination does not appear to be part of America's plan as of 2025.

One obstacle to improving the state's data structure is getting everyone to use systems that treat data in compatible ways. Another is the complexity of ensuring that the systems effectively protect the privacy of students and teachers. Big businesses and government organizations face these issues all the time — they can be solved with leadership and work. Finding the leadership to sort out California's education data haystacks is a complex problem. For one thing, it's unclear who is in charge. School districts are substantially left to find their own ways of solving data problems. Getting them to do things the same way, or even use the same data definitions, can run afoul of California's laws against creating state mandates.

Data issues may seem boring. They rarely fire up the passions of politicians, education activists, or parent leaders. But it seems inconceivable that this data weakness can continue forever in America, especially in California, the home of Silicon Valley.

A new beginning?

There is no good reason for optimism about improvement in data about education at the federal level. At the state level, however, California has been improving, at long last. For years, education advisory committees such as the Governor's Committee on Education Excellence recommended that the state establish a data commission to facilitate decisions about standards and points of integration, including data from social services, teacher-related systems, employment systems and higher education. California now has that commission.

In 2018 Governor Gavin Newsom campaigned for office pledging change: "Overarching all of this work — from prenatal to college and career — is my promise for California to reassert itself as an education data leader. The public deserves to know whether all students, regardless of background, have access to good schools and equitable funding."

It's worth noting that the Governor's emphasis has been on data about students and programs, but not teachers. While California has recently updated standards for teachers (2024), it consistently lacks mechanisms to use those standards in evaluation or improvement. In fact, for many years the Department of Education could not even commit to a simple count of the number of teachers in the state, much less make judgments about their effectiveness.

Updated July 2025

Quiz×

CHAPTER 9:

Success

-

Success

Overview of Chapter 9 -

Measures of Success in Education

For Kids and For Schools -

Student Success

How Well is My Kid Doing in School? -

Standardized Tests

How Should We Measure Student Learning? -

College Readiness

Preparing Students for College and Career -

Education Data in California

Keeping Track of the School System -

Achievement Gaps

The Education System's Biggest Challenge -

The California School Dashboard

Measuring California School Performance -

College in California

Options After High School -

Paying for College in California

Are College Loans Good For Students?

Related

-

Grade Inflation

Wishful Thinking and Cognitive Bias -

Are Schools Improving?

Progress in Education -

Accountability in Education

Who Monitors the Quality of Schools? -

School Funding

How Money Reaches the Classroom -

Do California Schools Waste Money?

Is Education Money Well Spent? -

Measures of Success in Education

For Kids and For Schools -

Student Success

How Well is My Kid Doing in School? -

College Readiness

Preparing Students for College and Career -

Achievement Gaps

The Education System's Biggest Challenge -

The California School Dashboard

Measuring California School Performance

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Steve R February 17, 2026 at 11:51 am

Carol Kocivar April 24, 2025 at 11:46 am

The Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), a key online library managed by the US Education Department, is at risk of losing funding due to budget cuts by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). ERIC is set to run out of money, which would halt updates and limit access to educational research.

Full Story: The Hechinger Report

Carol Kocivar April 24, 2025 at 11:45 am

The National Assessment of Educational Progress will reduce its scope in the coming years after significant budget cuts to the National Center for Education Statistics by the Trump administration. The changes include the elimination of some science and history tests for 12th-graders and reduction of the availability of some state-by-state data on student performance. Full Story: Education Week (4/21) Source: National Association of State Boards of Education

D Snyder March 3, 2025 at 5:47 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder July 16, 2023 at 1:29 pm

The freshest data about course enrollment available from the CDE is now literally an astonishing four years old, which I believe might be a new record.

Jeff Camp - Founder July 7, 2022 at 9:59 pm

francisco molina August 31, 2022 at 6:34 pm

Leigh Boghoussian February 5, 2020 at 11:13 am

This lesson was one of the most discouraging for me to read - representative of short-sighted thinking and the impacts thereof.

Susannah Baxendale March 22, 2019 at 4:01 pm

Jamie Kiffel-Alcheh December 7, 2019 at 3:41 pm

francisco molina March 1, 2019 at 1:48 am

Jeff Camp August 24, 2018 at 11:09 pm

Jeff Camp July 4, 2018 at 12:41 pm

Gloria Lucioni January 6, 2019 at 10:06 pm

Carol Kocivar June 18, 2018 at 6:46 am

It finds that the fragmentation of California’s education data systems makes it nearly impossible for the state to assess how well its students are progressing from high school, to and through college, and into the workforce.

Read the report.

Jeff Camp - Founder April 24, 2018 at 3:15 pm

Iris December 1, 2017 at 7:02 pm

Caryn-C September 15, 2017 at 8:56 am

We are lucky to participate in a district with pretty solid education data systems, at least from this parent's perspective.

I loved the infographic showing "what could be". In an underfunded classroom of 30 plus students, sorry Joey--no way would you get that kind of intervention.

g4joer6 April 22, 2015 at 11:31 pm

"Imagine if Amazon.com were unable to keep track of customer purchases. Imagine a pharmaceutical company unable to tell one pill from another. Or a bank losing track of accounts. In the last few decades, the world has become accustomed to organizations that can keep track of things in large numbers, in great detail.

Education has a long way to go in that regard, especially in California."