Chaos and learning don't generally mix well.

In This Lesson

How can schools discipline ethically?

What kind of school discipline works?

How can teachers learn to keep order in the classroom?

Is corporal punishment legal in California?

Is zero tolerance effective in school discipline?

What is restorative justice?

Are schools becoming more dangerous?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

Discipline is a critical element of a functioning school, and international research suggests that order in the classroom is an essential quality of an effective place for learning.

Establishing order in the classroom

Some teachers are masters at bringing their classes to order, and their techniques are worthy of study. Doug Lemov's books, including Teach Like a Champion offer practical tips based on successful teachers. The New Teacher Center helps train coaches for new teachers, who may struggle to establish order in their classroom. Learning the techniques of classroom control is a part of most teacher induction programs. And, of course, teachers share their classroom control hacks on YouTube:

When kids get into trouble at school, teachers must decide how to respond. Should they ignore it?

Schools and districts create discipline policies to give teachers guidance about what to do when stuff gets real. Students and parents need to understand behavior expectations and the consequences for bad behavior.

Corporal punishment in schools

School discipline may still include spanking, slapping and other forms of corporal punishment, in at least 18 states as of 2021. These practices are prohibited under California law. However, it’s still a debated method of disciplining students at school.

- Those who support of corporal punishment options in school argue that it can serve a deterrent purpose, and that it is less damaging to students than measures that remove students from the learning environment.

- Opponents argue that inflicting physical pain is barbaric and sets a bad example for conflict resolution.

In order to create consequences for bad behavior, some schools (and many more teachers) develop positive reward systems for good behavior, such as special recognition, in-class movies, and more. Withholding such incentives can help create consequences that students care about.

Police in schools

Keeping discipline in a classroom can be distracting, especially when things escalate and emotions come into play. Teachers call on one another for help, or escalate issues to administrators. To support schools, some communities employ resource officers, which are badge-bearing police officers assigned to work in schools.

In the wake of multiple violent incidents involving police in 2020, the use of such officers in schools was increasingly called into question. While the research on the subject is nuanced, it is clearly true that the presence of police in schools leads to more arrests - disproportionately of students of color and other minority students. Having an arrest record changes a student’s life, and there is evidence that it can contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline. The ACLU discusses the effects of police presence on campus discipline in a report titled the Campus Police Toolkit.

Zero tolerance policies

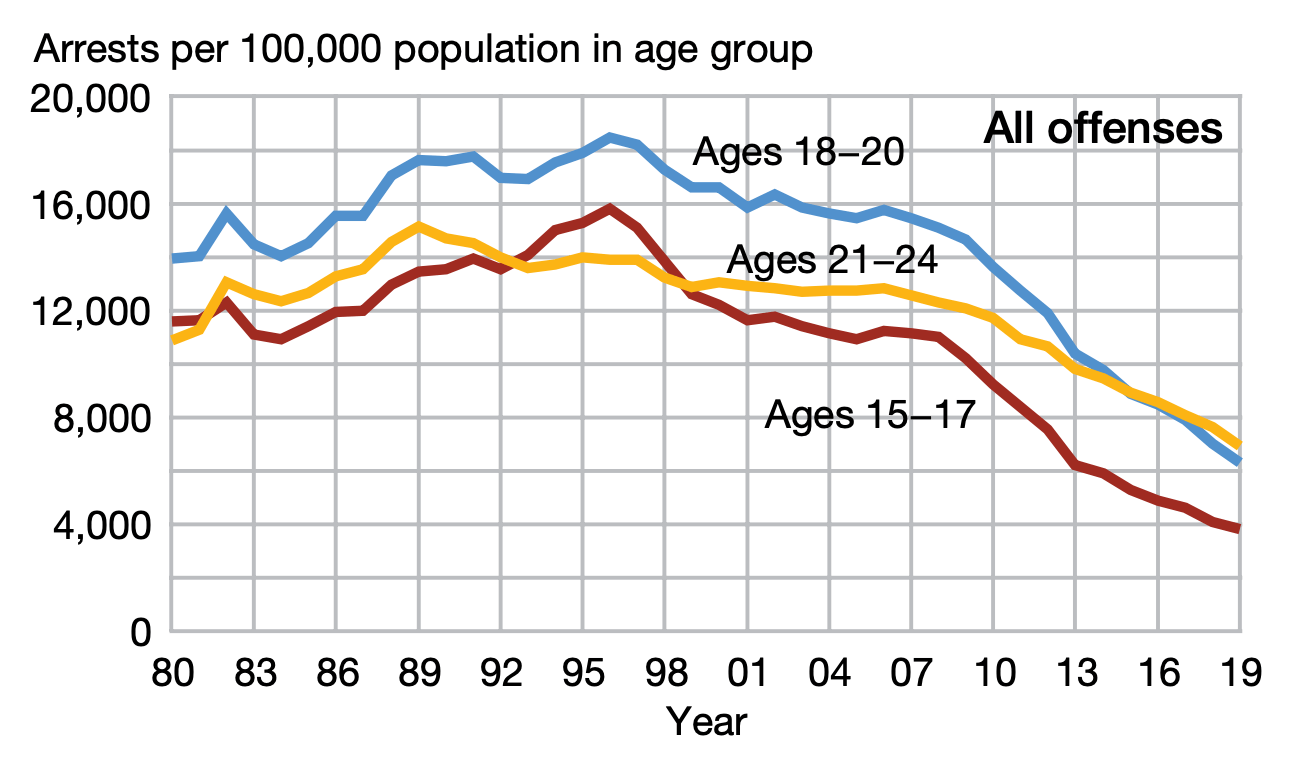

Each year, thousands of school-age children in California are arrested. About half that number end up in a juvenile court, and in turn about two-thirds of those children are declared wards of the state. The siphoning of students to jail is known as the school-to-prison pipeline. Placing students in a state or county juvenile incarceration facility is costly to the public in every sense. It's important to note, though, that the long-term trends are good:

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, 2021

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, 2021For those interested in learning more, the California Legislative Analyst Office's primer on California's Criminal Justice System is a helpful source.

The juvenile arrest rate peaked in 1996 and has been declining for decades. This isn't to say everything is dandy, of course. Bad stuff happens to kids, and some of it happens in school. The US National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) collects data about school safety and crime. The data are eye-popping.

A crime happened at more than three quarters of schools. Half a million girls felt unsafe.

For example, the 2019-20 survey indicated that a crime had happened at more than three quarters (77%) of schools, and nearly half of schools had reported an incident to police (47%). There were violent incidents in 70% of public schools, with 32% reported to police. In a 2019 survey, about 5% of girls aged 12-18 reported that they were "sometimes" or "almost always" afraid that someone would harm them at school, with the rate highest for the youngest respondents. The long-term trend is strongly in the right direction, but a rate of 5% represents half a million girls in America who feel afraid at school. As usual, averages conceal deeper patterns: the survey also found that nearly 7.5% of Black students aged 12-18 and 7% of Hispanic students are afraid of attack or harm during the school year, which is corrosive to a positive school climate.

Teachers don't necessarily feel safe at school, either. In a 2012 survey more than 7% of teachers in California reported having been physically threatened by a student, and more than 4% reported having been physically attacked. According to national statistics, threats and attacks against teachers are significantly more common in elementary schools than in secondary schools.

Federal law requires that students who bring guns to school be expelled. California, like other states, also has zero tolerance for additional offenses...

California law establishes that schools are gun-free zones. Federal law calls for zero tolerance — students who bring guns to school must be expelled. The rule is rigidly enforced. On your first offense, you're done.

Like many other states, California also has zero tolerance for additional offenses, such as brandishing a knife, possessing controlled substances, and sexual assault. When these mandatory expulsion laws were passed, states often added additional provisions to give local districts the option to suspend or expel students for a variety of other offenses. Districts in turn adopted their own zero-tolerance policies. The premise of these strict policies is that they help ensure that schools are safe.

Unless a student's misbehavior requires police involvement, a school's main official disciplinary options are detention, suspension, and expulsion.

In 2011, the Justice Center and PPRI sponsored an extensive analysis of empirical data about disciplinary practices in the state of Texas, titled Breaking Schools' Rules. The report quantified what many suspected: boys end up in trouble in school more often than girls, and Black and Latino students end up in trouble more often than white and Asian students.

Detentions, suspensions and expulsions do harm.

Vigorous and fair enforcement of rules seems like a good idea, but there is disappointingly little evidence that zero tolerance improves outcomes for students. In fact, there is a growing consensus among educators and researchers that detentions, suspensions and expulsions do harm. Strict and punitive disciplinary policies in middle schools lead to measurably bad outcomes for kids and for society. Removing young people from the active learning environment may turn those students toward permanent school failure without making schools safer or more effective.

Responding to these findings, schools in California are strongly reducing the use of suspension in school discipline. Still, the amount of school missed for discipline cases is pretty massive. According to data assembled by the Center for Civil Rights Remedies, "In 2016-17, schoolchildren in California lost an estimated 763,690 days of instruction time, a figure based on the combined total of 381,845 in-school suspensions (ISS) and out-of-school suspensions (OSS)."

Alternatives to zero tolerance policies

A growing chorus of researchers, educators, and advocates say that alternatives to zero tolerance do more to result in safe, orderly campuses. They argue that students can and should be explicitly taught how to behave in the school setting, even under provocation. They make the case that a more flexible approach to discipline can keep a much greater number of students in school and out of the juvenile justice system.

A 2008 report from the American Psychological Association (APA) set out principles to guide local schools and districts toward more effective discipline policies. The report takes the position that local policies should make it absolutely clear to students, staff, and parents that certain behaviors or offenses are unacceptable under any circumstances.

|

The APA recommendations include: |

|

|---|---|

|

Expulsion is rare |

Reserve expulsion for only the most serious offenses that place other students or staff in jeopardy of physical or emotional harm. |

|

Separate if necessary |

Focus on keeping students in an active learning environment, even in a separate facility if necessary. |

|

Use discretion |

Faculty have discretion in handling all but the most serious or serial infractions, using a clear method for making appropriate discipline choices with escalating options. |

|

Define consequences |

The disciplinary policy provides guidance to school personnel regarding permissible or recommended consequences for a given severity of the behavior. |

|

Define behaviors |

Behaviors subject to disciplinary action are carefully and clearly defined. |

|

Collaborate |

Local communities institute systems in which education, mental health, juvenile justice, and other youth-serving agencies collaborate to develop integrated services. |

Prevention and Restorative Justice

Behavior programs aim to modify an area of behavior for a specific age group. Some are preventative programs for all children and others work as interventions. Restorative justice is a process for working with students (both the victim and the accused perpetrator) to come to an individualized solution that repairs the harms caused by crime. Students often meet face-to-face in small groups to talk out their grievances and come to a personalized solution to the problem together. Positive Behavioral Intervention Systems (PBIS) is another common example. The research literature also makes a strong case that parents and community members have a strong role to play.

All California school districts must include school climate outcome measures in their Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP).

All California school districts must include school climate outcome measures in their Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP). The required indicators include pupil suspension and expulsion rates, to which local measures of safety and school connectedness can be added.

School communities don't have to invent their own programs to reduce conflict — they can turn to organizations that already focus on the issue. For example, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights has a strong record of helping schools intervene to help at-risk kids stay in school and out of trouble. The Niroga Institute has studied approaches to reducing school violence and conflict by teaching students techniques of self-control through the practice of yoga.

Schools are getting safer

Although there is plenty of room for improvement, there is also plenty of reason for optimism about school safety. By every available measure, schools appear to be growing safer. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) collects survey data about incidents, and the long-term trend is clearly good. (The chart shows the percentage of students aged 12-18 who reported having been a victim during the previous 12 months. using data from the survey. More data can be found in the 2021 Report on Indicators of School Crime and Safety.

This lesson concludes this chapter on "places for learning." The next chapter examines the "stuff" of learning, including curriculum, assessments, technology, and more.

Updated July 2017, June 2018, October 2018, August 2021, August 2022, November 2022.

Quiz×

CHAPTER 5:

Places For Learning

-

Places For Learning

Overview of Chapter 5 -

Where Are the Good Schools?

Zip Codes and School Quality -

School Choice

Policies for Placing Students -

Selective School Programs

How Schools Sort Students -

Continuation Schools

When Regular School Doesn't Cut It -

Charter Schools

Public Schools, Different Rules -

Private Schools

Tuition, Vouchers, and Religion -

Community Schools

Services Beyond Classwork -

Principals and Superintendents

The Pivotal Role of an Educational Leader -

School Facilities

What Should a School Look Like? -

School Climate

What Makes a School Good? -

Small Schools

Are They Better? -

Home Schools

How Do They Work? -

School Discipline and Safety

Suspensions and Other Options

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Carol Kocivar November 4, 2025 at 4:19 pm

"To better understand what happens when police are removed from schools, WestEd conducted a mixed-methods study to examine the impact of school police reform on student safety, behavior, well-being, and disciplinary outcomes in California schools.... Preliminary results suggest that although police reform didn’t affect discipline rates, student behavior, or safety perceptions, removing police from schools enhances student–staff relationships, improves student engagement, and protects against negative outcomes linked to insufficient mental health staffing."

Carol Kocivar October 4, 2025 at 5:16 pm

"Despite their widespread use, punitive approaches to discipline do not work to improve student behavior or safety. Zero tolerance policies that focus primarily on punishing negative behavior can decrease academic achievement and student perception of safety while also increasing rates of dropout, problem behaviors, and involvement in the criminal justice system"

-- American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, 2008; Monahan et al., 2014).

Carol Kocivar May 1, 2025 at 8:09 pm

The link below takes you to advice to school districts on disproportionate discipline based on race or ethnic background.

https://www.cde.ca.gov/ls/ss/se/schooldiscipline.asp

Jeff Camp - Founder December 5, 2023 at 7:31 pm

Carol Kocivar April 26, 2023 at 7:41 pm

From West Ed

An analysis of suspension rates and school climate at California middle schools finds that climate improved the most in schools with the greatest declines in out-of-school suspension rates. And there was no evidence that reduced suspension rates led to reduced safety.

https://www.wested.org/resources/suspensions-and-school-climate/?utm_source=e-bulletin&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=2023-04-issue-1#content

Carol Kocivar April 26, 2023 at 6:56 pm

The legislative analyst simplifies this for us in its "Overview of Juvenile Justice System and Education Services in Juvenile Facilities."

https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Detail/4760?utm_source=Legislative+Analyst%27s+Office&utm_campaign=da35b1ae28-RSS_EMAIL_K-12_EDUCATION&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_230ef9f9f2-da35b1ae28-517612179

Carol Kocivar May 11, 2022 at 5:57 pm

Suspension can do more harm than good. Sending a student home from school does not address the root cause of a student’s behavior; it removes students from the learning environment; and it has a disproportionate impact on African American students and students with disabilities, among other marginalized groups that are underperforming academically and overrepresented in our criminal justice system. Legislation in recent years, reflecting extensive research, has sought to minimize the use and impact of suspension. https://www.cde.ca.gov/nr/el/le/yr21ltr0819.asp

Selisa Loeza October 24, 2021 at 9:10 pm

http://openhood.org/homeroom/

[email protected] Madrigal July 12, 2020 at 10:26 am

Jamie Kiffel-Alcheh November 9, 2019 at 7:36 am

Susannah Baxendale January 25, 2019 at 4:52 pm

Caryn January 30, 2019 at 10:14 am

nkbird August 10, 2018 at 12:58 pm

Jeff Camp May 14, 2018 at 9:53 pm

Carol Kocivar November 4, 2017 at 9:44 am

Jeff Camp - Founder May 5, 2017 at 11:10 am

Jeff Camp January 13, 2017 at 9:45 am

Carol Kocivar October 27, 2016 at 3:24 pm

Why Are 19 States Still Allowing Corporal Punishment in Schools? Read the study from the National Education Association:

http://neatoday.org/2016/10/17/corporal-punishment-in-schools/

Jeff Camp - Founder November 9, 2015 at 10:48 am

Mamabear March 20, 2015 at 5:06 pm