What's an LCAP?

The Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP) is a three-year plan that each school district in California must update and make public each year. It is the central tool of the state's accountability system for public education.

In This Lesson

How did school funding used to work?

What is subsidiarity?

What did Proposition 13 do for education accountability?

What is categorical funding?

Who controls funding in California education?

Does the state hold schools accountable?

Who holds school districts accountable for distribution of funds?

What is an LCAP?

What are the requirements of an LCAP?

How is parent engagement required in the LCAP?

How are LCAPs approved?

How does local control funding work with collective bargaining?

What happened to the LCAP in 2020?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

School districts and charter schools in California use the LCAP to officially document their goals and plans, organized into eight priority areas. After public comment, the plan becomes official when the school board adopts it as part of the budget process. Both the budget and the plan are subject to review by the County Office of Education.

This lesson explains how the LCAP came to be and why it matters. To understand it, some background helps.

Before LCFF: The bad old days

The old system was bananas

California's system for funding public schools has changed dramatically over time. Prior to 2013, the system was bananas. (Read Lesson 8.4 for background.) A series of court cases in the state had produced a system in which some funds were determined by historical precedents, which had become disconnected with needs as the state grew. Other funds were determined and overseen by a crazy quilt of laws. Frustrated voters passed Proposition 13, which undermined education funding, then Proposition 98, which propped it up. Legislators, looking out for the interests of their constituents, directed funds toward specific categorical programs that would benefit them. Education resources flowed from Sacramento with growing limitations and program requirements, like coupons with fine print.

This arrangement was irritating, inefficient, and unfair. Unintentionally, it gradually centralized power over public education at the state level. But the system functioned so long as tax revenues continued to flow and grow.

They didn't.

In governance, subsidiarity is the philosophy that a central authority should only perform tasks that cannot be addressed at a more immediate or local level.

This philosophy was an essential element of the switch to LCFF under the leadership of Governor Jerry Brown, who decentralized control over education funds and placed power in the hands of school districts.

In 2008, the Great Recession punctured the economy. The stock market dropped. Tax receipts fell, leaving school districts with insufficient money to operate without dipping into restricted categorical funding. Which programs should be cut? Rather than picking winners and losers to preserve a bad system, Governor Brown worked with legislative leaders to use the crisis as an opportunity for change. Fortunately, a vision for a different system was already in place: dismantle the state's categorical funding system and replace it with something rational. The new funding system, finally adopted in 2013, was dubbed the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). It called for dramatically decentralizing control over funds. Under LCFF, school districts were given substantial power over the use of money, in exchange for increased transparency and public accountability for results.

Is accountability possible with local control?

LCFF placed a new degree of power in the hands of California's local districts and school boards. Would their decisions tend to benefit the students in most need of help, or the students whose parents had the strongest voice? Or, perhaps, neither? As discussed in Lesson 7.1 constitutional responsibility for education falls to the state, not to districts. Subsidiarity (see box above) is a governing principle, not a constitutional promise.

Meanwhile, a bunch of things were changing at the same time:

- The standards. California's academic standards changed with the state's adoption of Common Core standards.

- The tests. Tests changed to match the new standards.

- The scoring system. The old system was replaced with the California School Dashboard.

- Reporting of results. The Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP) was developed to provide public transparency about district plans and results.

There are two general options for holding an organization accountable. It can be held accountable for inputs (what it spends and how) or outcomes (what it accomplishes). California has tried to use both.

State Tests and State Accountability

Federal law (NCLB, then ESSA) requires that students take tests each year based on grade-level standards. This requirement has changed over time. So have the tests and the ways they are used.

Prior to 2013, under the No Child Left Behind act (NCLB), annual state tests served as the primary outcome-based accountability measure for schools and districts. That is, a school was officially seen as good if its students’ test scores were consistently high or consistently improving. For all their flaws, these tests at least provided some transparency. Virtually every student took them. Wherever groups of students bombed the tests, patterns stood out at every level — from the student, to the parent, to the school, to the district, to Sacramento, to Washington. California used the scores to create a measure for accountability under state law, the Academic Performance Index (API). This measure was also used as evidence of Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) required under the federal No Child Left Behind Act.

In this system, the state and federal government were assigned the "bad guy" role, responsible for drawing attention to inadequate results and demanding better. District, school, and teacher leaders often felt like victims with a “kick me” sign taped on their back. The NCLB law became unpopular, and Congress failed to amend it to make it effective. In the lame duck session at the end of the Obama administration, Congress chucked NCLB and replaced it with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), essentially eliminating Federal expectations for school results.

The system lost its bad guy.

Local Control requires local accountability

California's local control funding system turned the accountability system on its head. Don’t look to Washington or Sacramento to be the bad guy. Don’t count on some higher authority to expect excellence from your teachers and students. Under the principle of local control, communities are expected to make choices, safeguard the vulnerable, and achieve good results for all kids.

This approach deeply worries many civil rights advocates. A system that relies on community self-accountability is a system that can easily have lax accountability.

How does the LCAP work?

Each district, County Office of Education (COE), and charter school (collectively known as Local Educational Agencies, or LEAs) is responsible for preparing a Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP) that contains specific required elements. The plan describes the overall vision for students, annual goals, and specific actions that will be taken to achieve the vision and goals.

The LCAP is developed and reviewed each year in coordination with the district’s annual budget cycle. Each year the state evolves its LCAP Template, which districts use as a starting point. (They may design their own documents if they meet the requirements.)

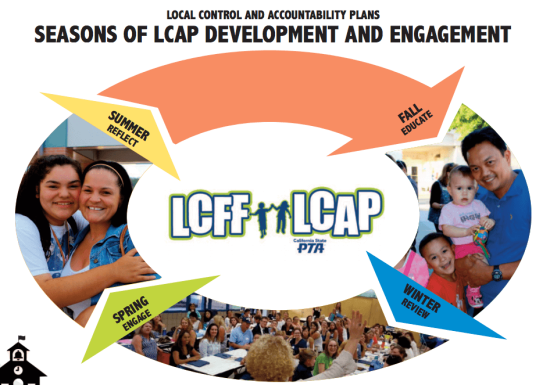

The California State PTA describes the cycle as Seasons of the LCAP. Ed100 and the California State PTA teamed up to develop a checklist to help community members make sense of the LCAP and contribute their feedback in a productive way.

The district-level LCAP, in combination with the school-level School Plan for Student Achievement (SPSA, usually pronounced SIP-suh), can help focus action-based conversations about local investment decisions.

Or, unread, it can just be paperwork.

The LCAP must address state-defined priorities

District (LEA) plans have to specifically describe how they will serve students in groups that are associated with additional funding under the LCFF system (low-income students, English learners, and foster youth). Plans for students who qualify for Special Education are separate from the LCAP process.

California's 8 State Priorities | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Student access to basic school services: fully credentialed teachers, instructional materials that align with state standards, and safe facilities. |

| 2 | Implementation of academic standards adopted by the State Board of Education (e.g. Common Core State Standards in English language arts and math, Next Generation Science Standards, English language development), including how programs and services will enable English learners to access the Common Core standards. |

| 3 | Parent involvement and participation, so the local community is engaged in the decision-making process at the district and school sites, including promoting parent participation in programs for high need students. [emphasis added] |

| 4 | Student achievement and outcomes along multiple measures, including test scores, English proficiency, and college- and career-readiness. |

| 5 | Student engagement, including whether students attend school or are chronically absent, and whether they graduate or drop out. |

| 6 | School climate and connectedness as measured by suspension and expulsion rates and other locally identified means. |

| 7 | Pupil access to and enrollment in a broad course of study, including all core subject areas (i.e. English, mathematics, social science, science, visual and performing arts, health, physical education, career and technical education, etc.). |

| 8 | Other student outcomes, if available, in the subject areas that make up the broad course of study. |

Districts can add additional goals into their plans for to reflect local priorities. County offices of education have to address two additional priorites.

The public must be engaged and informed

Each school district must engage parents, educators, employees and the community as they develop these district-level plans. The district plan should harmonize with each school's School Plan for Student Achievement.

How does that actually happen?

The State Board of Education provides templates that districts can use for their LCAPs. The first section of the template asks for information about stakeholder engagement. The plans must include goal statements linked to the eight state priorities and budget information showing how districts will pay for the program changes and improvements needed to meet those goals.

LCAPs must be reviewed by a parent committee — especially if a district has many English learners.

The plans cover three years, updated annually. The update process must include consultation with various constituencies, including teachers and parents. Ultimately, the plan must be reviewed by a parent advisory committee. If at least 15 percent of the students in a district are English learners, a separate parent committee (DELAC) must provide feedback for the plan.

LCAPs must be approved by each school board at the same time as the district’s budget, and they are subject to review by the County Office of Education (COE). This process has made COEs a much more important and substantial part of the education system than they were before LCFF became law.

LCAPs and Collective Bargaining

The requirement for each district to create its own accountability plan (LCAP) originated as part of the shift away from state-level mandates about how districts use funds. Civil rights advocates expressed concern that in the process of collective bargaining, resources that LCFF allocates on the basis of student needs might be swept up into across-the-board teacher salary increases, despite the spirit of the law.

The LCAP was a compromise solution. In principle, it was intended to provide local discretion about the use of funds in exchange for transparency. In practice, districts have varied in their commitment to disclosure. It is up to each community to dig into the numbers, ask questions, and enforce the intent of the law.

The LCAP during the COVID-19 pandemic

The pandemic required some temporary changes in the LCAP. For a single year (2020-21) California changed its requirements and guidelines for distance learning and layoffs. It also redefined “LCAP” with a new, temporary meaning: the Learning Continuity and Attendance Plan. (You may notice that the two plans conveniently have the same acronym. Clever, right?) For that single year, districts were directed to use their LCAP process to develop plans for educating all the students in their care through a combination of in-person and remote learning.

This lesson was updated in January 2025.

Quiz×

CHAPTER 7:

And a System…

-

And a System…

Overview of Chapter 7 -

The Role of State Government in Education

California’s Constitutional Responsibility -

The Federal Government and Education

Small money, Big Influence -

School Districts in California

What do School Districts Do? -

County Offices of Education

Oversight and Regional Services -

Teachers' Unions in California

What do Teacher Unions Do? -

Ballot Initiatives and Education

California's Initiative Process and How It Affects Schools -

Who Influences Education?

Politics, Philanthropy and Policy -

Accountability in Education

Who Monitors the Quality of Schools? -

What to Do with Failing Schools

Interventions and Consequences in California -

The LCAP

Annual Plans for California School Districts

Related

-

The Role of Parents

Education and Families -

The Role of State Government in Education

California’s Constitutional Responsibility -

School Districts in California

What do School Districts Do? -

County Offices of Education

Oversight and Regional Services -

Education Data in California

Keeping Track of the School System -

The California School Dashboard

Measuring California School Performance

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Jeff Camp - Founder June 29, 2024 at 2:22 pm

Sheila Melo May 30, 2020 at 9:47 pm

Denise Dafflon December 10, 2019 at 9:27 pm

Caryn December 11, 2019 at 11:59 am

Denise Dafflon September 11, 2019 at 2:48 pm

francisco molina July 20, 2019 at 12:06 am

francisco molina July 19, 2019 at 11:25 pm

Denise Dafflon September 11, 2019 at 2:59 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder September 7, 2016 at 2:52 pm

http://cacollaborative.org/sites/default/files/CA_Collaborative_LCFF__4.pdf?utm_source=Ed100

Carol Kocivar July 14, 2016 at 8:06 pm

http://www.ppic.org/main/publication.asp?i=1202

Carol Kocivar April 23, 2016 at 2:57 pm

Here is a link to the report: https://west.edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/11/ETW-April-2016-Report-Puzzling-Plans-and-Budgets-Final.pdf

Carol Kocivar December 11, 2015 at 4:19 pm

Highlights

Districts are unclear about the purpose of the LCAP and unsure about what funds to include in it. In addition, they are confused about the cycle and annual updates and view the LCAP as a compliance document.

The bad news: They produce LCAPs that are neither readable by nor accessible to the public.

Another finding:

Public awareness of the LCFF still lags, which may be complicating engagement efforts.

Download the report:http://edpolicyinca.org/sites/default/files/LCFF.pdf

Brandi Galasso September 24, 2015 at 12:33 am

KimS April 21, 2015 at 6:36 am

Since LCAP has been implemented, the only budgetary improvement I've seen in my child's school is that the library is open one day a week. Class sizes stayed the same or got bigger; the school lost its ELST/reading specialist hybrid position. I want to embrace LCAP but having the people who implement the LCAP assess its effectiveness is maybe not a wise plan.

Sherry Schnell April 2, 2015 at 9:28 am

maritess February 14, 2015 at 10:09 pm

Janet L. February 2, 2015 at 11:11 am

Jeff Camp - Founder February 2, 2015 at 1:54 pm

Janet L. February 2, 2015 at 5:26 pm

Mary Perry October 29, 2014 at 2:37 pm