Learning is fundamentally human work, and humans are complicated. To improve learning requires getting multiple things right at once. Even then, not all changes produce results. How do you cut through the distractions and get to what matters?

In This Lesson

What is the education reform "razor"?

How do changes in the education system happen?

What was the A Nation At Risk report?

Is the education system becoming more or less centralized?

How did California's education system change to "Local Control"?

What was "Getting Down to Facts"?

What was the Committee on Education Excellence?

How did Proposition 30 play a role in LCFF?

Why was the passage of the LCFF successful?

What factor can influence educational change the most?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

The history of education innovation is littered with magical thinking: “Just do this one thing, and all will be well!”

If only it were so easy. Many complex and costly education reforms, launched with great fanfare and hope, turn out to accomplish little or no measurable result. Fancy theories of change in education tend to fail in practice because, well, change turns out to be hard.

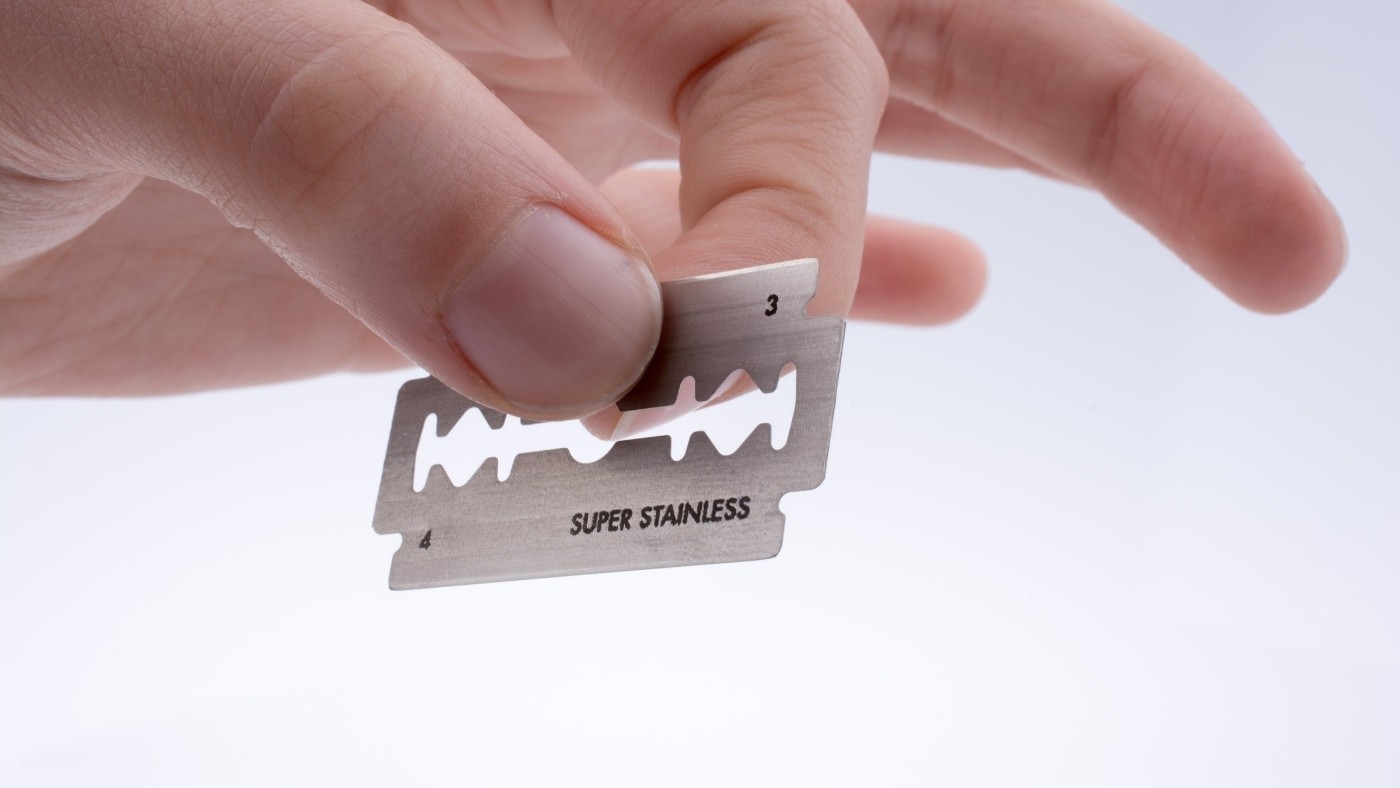

The Ed100 Razor:

“Will this idea change who is in the room, or how kids and teachers use time?”

A philosophical razor is a principle or rule of thumb to shave away distractions. There are many distractions in education. To test the potential of any idea meant to improve learning, consider this razor: “Will this idea change who is in the room, or how kids and teachers use time?” If it addresses neither, it probably won't make much of a difference. The same people will continue doing the same things.

The education system has tremendous inertia. Changing it even in small ways is hard; changing it significantly can seem impossible, even in the teeth of a pandemic.

Some reformers say that there are two competing approaches to changing education: top-down and bottom-up. This is too simple. Schools in California continuously experience a strong combination of top-down direction and bottom-up innovation.

Top-down direction in goals

To intentionally change education at scale implies big, top-down policy action. There are many important examples:

- Educational standards have not always existed. The 1983 report A Nation At Risk popularized the idea of formal grade-level expectations.

- The No Child Left Behind Act established that standards should be taken seriously for the education of all students.

- The IDEA Act established that "all students" would include those with disabilities.

- The Race to the Top competitive grant program prodded states with a “carrot” to get on board by updating their standards and making them consistent.

- The COVID-19 pandemic forced school systems to get serious about providing all families with access to computing resources.

Bottom-up innovation in means

Top-down mandates for change are often resented, and they can be clumsy in implementation. In response, states have passed laws to limit top-down mandates and encourage bottom-up innovation. The most important examples are charter school laws, which allow schools to operate separately from school districts. One argument for this separation, as discussed in Lesson 5.5, is for these schools to serve as “laboratories” to test and develop new approaches to achieving the standards.

California’s shift to Local Control led to less centralization

The way public education works in California was dominated by state-level policies for decades. The 1978 passage of Proposition 13 centralized budgetary power in Sacramento. In 2013, however, the state legislature passed the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), which shifted significant budgetary power to school districts. This opened up the possibility for traditional public schools to serve as laboratories, too. It was a big change, reversing the decades-long trend toward centralization.

LCFF was a case study for top-down change

In hindsight, it seems obvious that the school finance system should be based on students. But that's not how the system worked. The system was based on programs, not on people. The passage of LCFF was a revolutionary change in the school finance system. Just about everyone thought a change of this magnitude was impossible. The old system was foul, but familiar, and everyone had a stake in it. How did the change happen, and what can be learned from it?

From dusty reports... The ideas behind LCFF were not new. Policy analysts and academics had advised for years that the system needed re-thinking, particularly in the area of education finance. One panel had declared that California’s education finance system was a mess, calling it a “crazy quilt” and comparing it to the Winchester Mystery House.

...to coordinated research... In the early 2000s, a coalition of philanthropic organizations decided that the road to change would need to be paved with persuasion, and that persuasion would require information. They jointly funded Getting Down to Facts, an extensive, coordinated research effort to document how California's education system actually worked. Philanthropists also supported the costs to convene a new, independent advisory committee, the Governor's Committee on Education Excellence, charged with making policy recommendations based on the research. This coordination created new conditions for many of the influential voices in the education community to sing from the same hymnal.

...To One Report, apparently DOA. The committee released its long-awaited report in 2007. It recommended a suite of changes to the educational system, including significant increases in funding, to be implemented on the basis of student characteristics rather than on programs. The recommendation for additional spending was dead on arrival; as if on cue, the Great Recession buried any chance of increases.

Leadership... The proposal to base funding on students was well received, though most viewed it as idealistic and far-fetched, particularly in the context of falling state revenue. It was in this context that then-Governor Jerry Brown appointed Mike Kirst, a Stanford professor who had played a key role in the Getting Down to Facts project, to serve as President of the State Board of Education.

...and Timing... To sustain funding for the state’s hard-hit budget, Governor Brown decided to place a tax measure on the ballot (it became 2012 Proposition 30). Kirst advised the Governor and legislative leaders that this infusion of money, though limited and temporary, could actually serve as the right moment to fix the system. Like Mary Poppins with her spoonful of sugar, perhaps the tough medicine of LCFF could go down easier in bad conditions that might get better. (The political circumstances had changed, too — the election of 2012 was the first to take place in the context of California's top-two primary system.)

It was not at all obvious that LCFF could be passed into law. How did that happen, and what can be learned from it?

Against most expectations, the strategy worked. Voters understood that education funding was in crisis, perhaps partly because there were two education funding measures on the same ballot. Proposition 30 was the smaller of the two measures.

...Led to change in education. The passage of Prop 30 didn’t fully fill the revenue pothole created by the recession. In fact, it took about seven years for education funding to recover to pre-recession levels. Still, it blunted the impact. The subsequent budget act established a lengthy but clear timetable for a complete shift to Local Control funding based on defined student characteristics. Voters extended the taxes by passing Prop 55.

How and why did LCFF pass?

Was it the tightening belt of falling revenues that made the passage of LCFF possible? Or was it the lifeline of sustaining revenue offered by the passage of Prop 30? Political conditions of the moment were unusually straightforward: one party (the Democrats) held secure majorities in both houses, with clear leadership from Jerry Brown, an experienced Governor of the same party.

Perhaps the Getting Down to Facts research itself persuaded the policymakers to act; certainly, it created an unusual level of unity among the academics advising the legislature. Journalists, as well, may have felt the idea had unusual support; most academic research makes for heavy reading, but Stanford's Center for Education Policy Analysis prepared short summaries of the research and worked to make them readable for a general audience. (Disclosure: the authors of Ed100 were deeply involved in the Getting Down to Facts work.)

Whatever the combination of factors at play, the passage of LCFF was a top-down policy change that presented local leaders with new power. This change was such an unexpected and dramatic outcome that the Stuart and Kabcenell Foundations commissioned documentary research about how it happened. A set of follow-up studies was released in 2018 under the name: Getting Down to Facts II.

Education and wealth are tied

One of the key messages of Ed100 is that education is a complex system. There is no one magic answer.

Educational success drives economic well-being, and vice-versa.

In fact, if there is one truly vital point to take from all of the research about patterns of educational success, it is this: education and wealth are strongly tied. It does no good to imagine otherwise. In nations, states, and communities where families are struggling the hardest to get by, educational results and economic prospects suffer concurrently. In nations, states, and communities of plenty, educational prospects are generally bright.

In places where miracles seem to have occurred that beat the odds, it pays to look closer: not all poverty is alike, and statistics usually make grainy distinctions. This is not to say that exceptions never occur: we should celebrate and learn from them. But the connections between economic advantage and academic success are so incredibly strong that they often overwhelm the effects of other factors or programs.

The broadest driver of educational success is economic well-being, and the broadest driver of economic well-being is educational success. If you want to boost a community, it is easier standing on two legs than on one: find ways to lift academic success and also address human needs.

Updated July 2018

April 2019

August 2021

December 2022

Quiz×

CHAPTER 10:

So Now What?

-

So Now What?

Overview of Chapter 10 -

Should the Education System be Blown Up?

Would Disruption Help? -

What if Schools Had More Money?

What Do the Rich Schools Do? -

Are Lean School Budgets Good for Kids?

Do Lean Budgets Make Schools More Innovative? -

Change

What Causes Change in Education? -

Learn More About Education

Organizations and Resources

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Susannah Baxendale March 28, 2019 at 11:11 am

Caryn-C September 18, 2017 at 11:40 am

This is a great takeaway. Wishing it were different will never make it so. It's got to be a societal shift fueled by a populace that rejects the idea of California continuing its downward slide into educational oblivion.

Jeff Camp February 3, 2017 at 11:23 am

Carol Kocivar October 28, 2016 at 1:36 pm

"We are discovering what seems to work. Common elements are present in nearly every world-class education system, including a strong early education system, a reimagined

and professionalized teacher workforce, robust career and technical education programs, and a comprehensive, aligned system of education."

Read the report: http://www.ncsl.org/documents/educ/EDU_International_final_v3.pdf

Jeff Camp October 24, 2016 at 9:46 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder October 25, 2015 at 2:14 pm

Brandi Galasso April 18, 2015 at 7:10 pm

Mamabear April 12, 2015 at 2:35 pm

ed August 31, 2016 at 7:48 am