Tests (more formally known as assessments) have become an important part of the school experience in America.

In This Lesson

How do standardized tests work?

Are schools teaching to the test?

What are formative tests?

What are summative tests?

How is technology used in testing?

Does testing lead to a narrow curriculum?

What is a computer adaptive test?

Is it bad to teach to the test?

How did the Pandemic affect testing?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

Tests come in two main flavors: formative and summative. It's worth understanding the difference.

Formative Assessments

Teachers use formative assessments to check whether students understand material they have been taught. These tests are generally short, focused, and used to guide instruction. (“OK, students, it looks like some of you are fuzzy on the difference between a simile and a metaphor. What’s the difference… Andre?”)

Traditionally, teachers created formative tests themselves. Here's the problem: writing good test questions is really hard. Some teachers are good at it, but it's an area of expertise distinct from teaching, and it's time-consuming. As instructional materials have become more tightly aligned with standards, it has made sense for textbook publishers to include unit tests as part of their content. Bubble-test versions of these assessments can speed up scoring and give teachers rapid feedback. These assessments can also help teachers compare the effectiveness of their lessons so that they can work together to improve them.

Testing jargon: "Formative" assessments are like quizzes. Usually short, and used during a course to see if you're on track. "Summative" assessments are like final exams that happen after the course is done to render a grade.

Summative Assessments

Summative assessments are end-of-course or end-of-year tests. These tests assess cumulative knowledge of the content taught. All of the big standardized tests (CAASPP, SAT, ACT, TOEFL, HSE, AP, NAEP, PISA, and more) are summative. These tests permit comparisons between schools, teachers, programs and the like. They are also widely disliked.

Teachers do not get much useful feedback from the big annual standardized tests, which tend to deliver scores late and without much detail. Critics of testing aren't necessarily anti-test. Many simply argue that summative standardized testing takes up too much time for too little practical benefit.

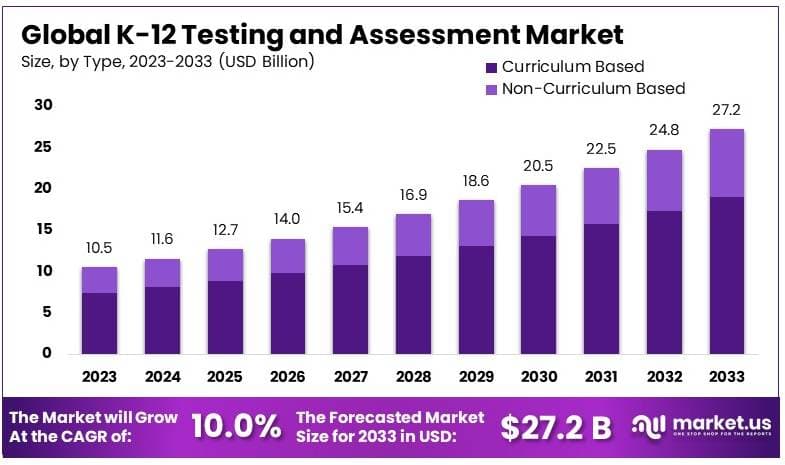

Although there is a great deal of emphasis on summative tests (after all, they count, right?) students and teachers spend more of their time on formative work. Because good test questions are hard to create, publishers have increasingly found schools and districts to be eager buyers of formative assessment tools for classroom use. Technavio (a consulting firm) estimated in 2022 that the market for products in the area of educational assessment is growing at a rate of more than $1 billion per year.

Technology for better testing

The distinctions between formative and summative tests have blurred. In the same way that games adapt to challenge the skills of the player, adaptive assessments adjust to find the boundaries of a student's readiness, avoiding questions that are either way too easy or way too hard.

If you feel as though your school is spending too much time and energy on tests, you might want to consider working with your principal or PTA leadership to gather some data. It is easier to have a productive conversation about the issue with facts in hand. Some have found it helpful to estimate the dollar value of time spent on testing. As discussed in Lesson 4.4, one way to go about this is to document the number of student-hours involved and multiply that by the current hourly pay rate for an entry-level barista.

What gets tested gets taught

In business, there is a saying that “what gets measured gets managed.” In education, the equivalent is “what gets tested gets taught.”

Over time, tested subjects such as math and English have received more focus than those measured less often. The tendency to spend more energy, time, and resources on tested subjects can result in a phenomenon called narrowing the curriculum, which has been observed in many developed nations.

One response to this narrowing has been to create more standards in other subject areas, as other lessons in this chapter describe. Standardized assessments exist for science and history/social studies. The standards for physical education, visual and performing arts, world languages, financial literacy, and career-technical education may guide instruction, but they get much less attention from state leaders or the public. To provide comparable structure for other subjects and skills, some proponents of a well-rounded education suggest standards should be adopted and tested for life skill learning such as time management, self-control, teamwork, and personal finance.

How did the pandemic change testing?

The pandemic upended many aspects of the educational system, including test-taking. Before the pandemic, most selective colleges required students to take the SAT or ACT as part of the application process. Many colleges and universities waived this requirement for 2020 applicants and then abandoned the requirements altogether.

For many years, colleges found standardized tests helpful as a way to identify strong applicants and defend their admissions decisions from charges of bias. By the time the pandemic began, many colleges were already looking to move beyond test scores in admission decisions in service of goals like diversity and inclusion. Since the pandemic, however, more and more schools across the country are bringing back testing requirements.

In the next lesson, we delve into the use of technology in education, which was transformed by the pandemic.

Updated January 2025

Quiz×

CHAPTER 6:

The Right Stuff

-

The Right Stuff

Overview of Chapter 6 -

Grade-Level Standards

What is the Common Core? -

Is School Challenging Enough?

Academic Rigor -

Literacy in California

Ensuring All Kids Can Read, Write and Speak English -

STEM Education in California

Science, Technology, Engineering and Math -

Why Are Tests Important?

Why Tests Matter and How They Work -

Technology in Education

Tools for Teaching and Learning -

Student Engagement

How to Make School Interesting -

Arts Education

Creativity in California Schools -

P.E. and School Sports

How Does Sweat and Movement Help Learning? -

Field Trips

Beyond the Classroom -

Career Technical Education

Vocational Learning, Dual-Enrollment, and Internships -

Service Learning

Civic Engagement and Helping Others -

Teaching Soft Skills

Social-Emotional Learning -

Can Values and Habits be Taught?

Character Education -

Civics, History and Geography

How Do Kids Learn About Their Country and the World? -

How do Kids Become Bilingual?

World Language Learning in California Schools -

Financial Literacy in California

Learning to Earn

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Carol Kocivar June 14, 2022 at 3:25 pm

francisco molina January 12, 2022 at 3:54 am

Susannah Baxendale February 2, 2019 at 11:44 am

Our daughter, a 4th grade math teacher, is finding that her students know concepts but are challenged to communicate them because of their literacy skills -- and, sadly, their computer skills. Assuming that all children have what it takes to do tests on the computer--and assuming that all schools have functioning computers for testing (NOT!), is something that is affecting her students considerably. I worry terribly about the dependence on computers--it is like an unfunded mandate--telling you to do things but not providing the wherewithal to do so.

Susannah Baxendale February 2, 2019 at 11:39 am

Matthew Rosin May 3, 2011 at 4:53 pm

For example, in these schools:

• Teachers frequently administer benchmark, diagnostic, and classroom-based assessments of student learning to inform their teaching. (Interviews we've conducted more recently make clear that these could include teacher- or school-developed quizzes, unit tests contained in the adopted curriculum, and district-wide benchmarks, and in some cases might be developed using standards-aligned item banks.)

• Teachers use the resulting feedback to better understand and set goals for the learning of individual students, and to rapidly identify any students needing additional support or intervention.

• Teachers also use these data to evaluate their own work, such as to collaborate with their peers around effective instruction.

• Further, principals use these data to follow student progress and examine teacher practice.

This ongoing feedback enables principals and teachers in higher-performing middle grades schools to make the most of the state content standards and their curricula and pacing guides.