In education, as in most everything, the ultimate scarce resource is time.

In This Lesson

What is the cost of an hour of school?

How can teachers make good use of school time?

Do teachers have time to prepare?

How do schools determine their schedules?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Discussion Guide

What does it mean to spend time well in education? How much is school time worth? This lesson looks for the answers.

How much is an instructional hour of K-12 worth?

As discussed in Lesson 4.3, there are roughly 1,000 instructional hours in an American school year. Given that, what’s the rough per-student cost of an instructional hour? Simple: it's the cost per year divided by a thousand.

Over time, the dollar cost of education has risen with inflation, a subject we discussed in some length in the context of teacher pay. As of 2024, the average annual cost per student in California public K-12 education was about $19,000 per student.

Rule of thumb: Students' time is more valuable than minimum wage

…which comes to about 19 bucks an hour, above minimum wage everywhere in California.

This rule of thumb can be handy for evaluating the rough dollar value of things that take time or save time in California schools. What value could we put on the instructional time lost in a one-hour bus delay that affects 50 students? How much instructional time cost could be recovered through smoother transitions between classes? How can we think about the instructional time cost of administering a standardized test, or of taking kids on a field trip? Putting a dollar value on instructional time per student doesn’t make tradeoffs simple, but it can help make them more concrete.

Time management in schools

The clock spins in only one direction. Each day, teachers have limited time to inspire and guide students through their lesson plans. Some teachers make masterful use of their limited minutes with students, elevating the use of time to an art form. In Teach Like a Champion and his other work, Doug Lemov describes techniques collected from master teachers that enable them to keep students engaged and learning, with practice. His instructional videos have become popular because they are practical. His primary thesis is that teaching skills can be learned and improved, with clear examples.

Time in school has a rhythm to it. Classes begin and end at scheduled times, marked by bells, buzzers or chimes. But do they have to be? In the past, clocks were rarely synchronized, but nowadays there is no longer any real doubt about the correct time. Factories and businesses have mostly done away with clocks that make noise, and some schools are getting rid of bells too.

Part of the rhythm is waking up. Before the pandemic, many schools started very early in the morning. Advocates from the PTA and the medical community highlighted research about the impact of sleep on learning led to changes in California laws in 2019: High schools must not begin the school day before 8:30 a.m. Middle schools must not begin before 8:00 a.m.

What is block scheduling?

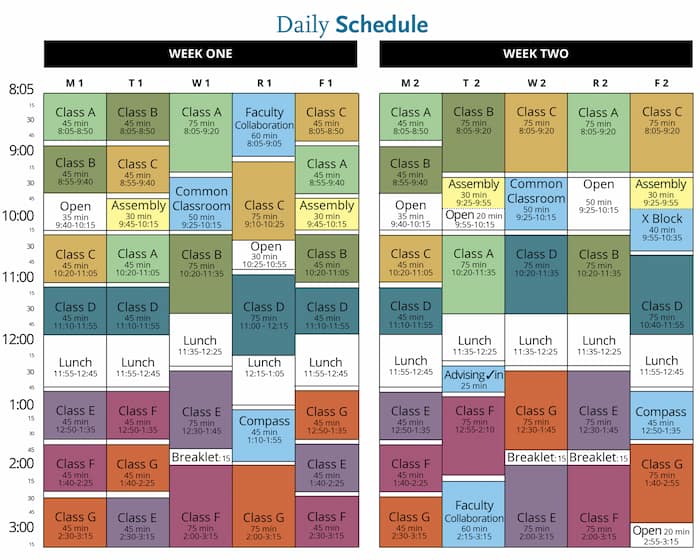

Traditionally, school days are chopped into class periods of equal length, but they don't have to be. Some schools use block scheduling to create a mix of longer and shorter instructional segments that differ from one day to the next. Long blocks of double the usual length reduce transition time between classes. They also enable teachers and students to delve deeper into discussions, problem sets, art projects and lab work. There are different types of block scheduling, each with its own set of benefits.

Some schools create overlapping class periods, with some students and teachers starting earlier and others ending later, in order to create flexibility and address space issues.

Changing something as fundamental as the use of time in school affects everyone involved; it can be transformative, but it is also easy to make mistakes. There is some evidence that longer class periods may be beneficial, but there are many approaches and no easy answers about what works best. The National Education Association (NEA) urges school leaders to plan carefully and talk it all through with teachers before jumping to a new schedule system.

Time to prepare.

To do anything well requires preparation, which takes time. In the context of school, teachers need to know their material and have a solid plan to teach it. In many countries, school systems set aside time [PDF] in the school day and the school calendar for teachers to collaborate and prepare (learn more in Chapter 3, Teachers). The Learning Policy Institute provides a good overview of how to use time effectively in professional development.

Updated in September, 2025

Quiz×

CHAPTER 4:

Spending Time...

-

Spending Time...

Overview of Chapter 4 -

Preschool and Kindergarten

Yes, Early Childhood Education Matters -

Class Size

How Big Should Classes Be? -

School Hours

Is There Enough Time To Learn? -

Time Management in School

Spending Time Well -

Tutoring

When Kids Need More Time and Attention -

Summer School

Time to Learn, or Time to Forget? -

After School Learning

Extending the School Day -

Attendance

Don't Miss School!

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Jeff Camp December 17, 2019 at 11:30 pm

Susannah Baxendale January 17, 2019 at 12:36 pm

Caryn January 17, 2019 at 1:04 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder September 16, 2017 at 6:41 pm

cnuptac March 22, 2015 at 6:29 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder March 23, 2015 at 6:30 pm

Mary Perry October 28, 2014 at 8:33 am

This new international data should make us ask the question again. http://www.ncee.org/2014/10/statistic-of-the-month-teachers-salaries-class-size-and-teaching-time/

In particular, put this data into a California context, where salary levels are relatively high but class sizes are way off the chart. Getting comparable data and placing your district on these charts might be illuminating.