GenAI and Media Literacy

What is GenAI?

You can’t read many articles about education these days without encountering something about Artificial Intelligence (AI). In the last few years we’ve seen swaths of commentary about how good or bad or exciting or scary it is. In that mix, you may have also heard of GenAI. Before we dive into some ways these tools are influencing education, let’s make sure we know what we’re talking about.

Michelle Parker

KQED | PBS

Generative AI (GenAI) is shorthand for Generative Artificial Intelligence. These are computer programs trained on large datasets to recognize patterns and then create new content such as text, images, audio, video, or code. GenAI doesn’t just repeat existing material. It generates new, original outputs that mimic the style, structure, or meaning of what it has been trained on.

While they don’t “think” or “understand” like people do, language-based GenAI tools are very good at predicting what words are likely to come next based on the patterns they’ve seen. Examples include ChatGPT (OpenAI), Gemini (Google), Claude (Anthropic), and Copilot (Microsoft).

There are lots of good resources available online for understanding what AI is and how it works. Some good overviews about its relationship to education are Common Sense Education’s “ChatGPT Foundations for K–12 Educators” or the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE)’s “Artificial Intelligence Exploration for Educators.”

Why are some people in education nervous about GenAI?

Cheating

Bias

Laziness

Privacy

Job security

Environment…

Hey, why worry?

Some educators and school leaders worry that students will use these tools to cheat, or that overreliance on GenAI will dull their learning. Some express concern that GenAI might replace educators, or that these tools won’t be used ethically. They might be concerned about data privacy for both students and educators. Some people are concerned about the environmental impact of AI. Some people want to pretend it doesn’t change anything.

Many school districts haven't yet set policies or position statements to directhow GenAI tools should or shouldn’t be used. And if they have, sometimes that policy is a blanket “no use is permitted” one and isn’t particularly strategic. Some guidelines for specific districts are available, but may not be widely known or used yet.

In September of 2024 the California legislature voted unanimously to direct the Department of Education to create an AI Working Group. The group’s first assignment, due January 1, is to propose initial guardrails and guidelines for the use of AI in education in K-12 public schools. A draft of a full model policy is due from the working group by July 1, 2026. According to the Education Commission of the States, California is in good company — many states are convening study groups before committing to a policy direction.

Arrived vs. Adopted

Normally, school districts get to choose among new technologies and adopt them methodically. That hasn’t been possible with AI — it just sort of arrived. There was no chance to review and assess options, choose among them, train teachers on them, and then roll them out. It just plopped into the education system’s lap. Sure, some districtsh ave been paying close attention as AI has evolved. But most just weren’t ready.

“...in the months and years ahead, new AI capacities will arrive in these systems without the same planning, intention, and oversight.”

For now, education leaders in schools and districts are somewhat on their own. As someone working with public media to provide services to educators and students, this is an exciting moment. Stories of innovation, success and failure are incredibly important right now.

GenAI and media literacy

I lead the education department at KQED, the local public media station here in the San Francisco Bay Area. We focus on strengthening students’ and educators’ media literacy skills and elevating youth voice. We use the National Association of Media Literacy Education (NAMLE) definition of media literacy: the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create and act using all forms of communication.

Media literacy skills are important no matter what technology is the latest and greatest. Get these skills down and you can navigate new technologies pretty well.

By the spring of 2024, many educators and school leaders we work with had expressed their uncertainty navigating this new AI landscape. With our media literacy expertise we wondered how we might provide useful guidance that could reduce fear, increase confidence, and encourage responsible and ethical use of GenAI tools, particularly in a way that honors youth voice and maintains their creativity and originality. We researched, learned, and experimented. We landed on some minor updates to our media literacy framework and a new set of free guidelines, and workshops and courses for educators.

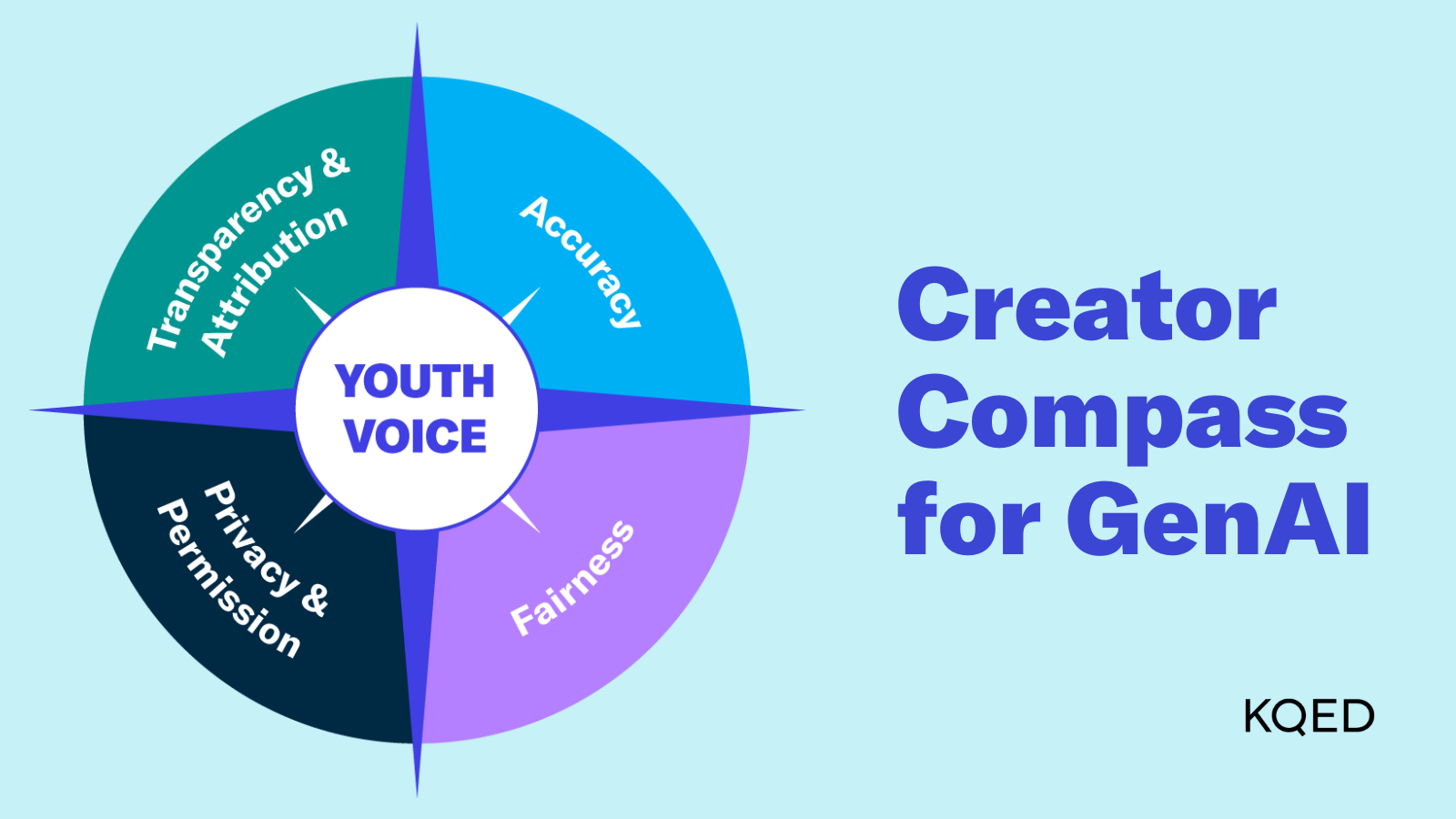

We developed a tool called the Creator Compass for AI. It illustrates a set of values, guidelines, and best practices to support the ethical use of GenAI in education.

At the center is youth voice—a core value. Surrounding it are four key principles: accuracy, fairness, privacy and permission, and transparency and attribution. The compass is meant to offer some direction and reassurance as they navigate this new terrain.

As an important output of this work, KQED recently released a series of free online courses focused on various aspects of GenAI and media literacy:

- Partner with GenAI to Elevate Authentic Student Voice

- Outsmart AI to Spot Misinformation and Evaluate Sources

- Break Through AI Bias to Analyze and Create Media

Think about some of these values and guidelines and how teaching works in your school. How do they align? How would you prioritize them? Is there anything missing? They can be a useful conversation starter for you and your friends or colleagues.

What else can educators do?

Obviously, making use of those KQED resources could be very helpful (shameless plug, I know—did I mention they’re free?).

One of the main questions in the education world is how we can use GenAI for the “right” things—the things that help and improve learning. Which parts of the learning process can actually work better or advance equity when you use GenAI to support them? And in contrast, which parts are worse if you bring GenAI tools in too early? This recent paper talks about the considerations when it comes to student writing.

It’s also important to learn how GenAI works, so you can better understand its limitations, e.g. hallucinations and common biases based on the data systems they’re trained on.

One thing to remember is that AI is constantly changing in its capabilities, accessibility, and consistency. Today's best practices might change tomorrow. Find some thought leaders to follow, practice using the tools yourself, and encourage educators in your schools to the same. A couple of suggestions on who to follow:

- Ethan Mollick: His blog and Substack “One Useful Thing” offer thoughtful experiments with the tools. He provides great insights across AI applications generally, and also has written specifically about the opportunity AI provides for education.

- Derek Muller (Veritasium): He has become a thoughtful commentator on AI in the context of the history of education. You can see one of his videos in this Ed100 lesson.

Some final thoughts

As we all navigate this increasingly complex landscape, here are a few tips based on my own experience with our work here at KQED:

- Keep humans in the loop. GenAI tools aren’t perfect and will make mistakes. Human ideas and creativity should be the beginning of any GenAI request. And importantly, human relationships still really matter—personally, in educational settings, and in other professional settings.

- Lateral reading skills (using the internet to check the internet) are important no matter how sophisticated GenAI gets. These skills apply to all kinds of media and information.

- Play and practice a lot with GenAI tools. It will make them less scary and easier to use.

- Talk about it! Build a culture where transparent experimentation with and use of GenAI tools is both safe and rewarded. Maintaining a culture where you can talk about it brings everyone along.

Hopefully you have some new actions to take and feel a little less hopeless or disempowered when it comes to GenAI and education. And don’t forget to connect with us at KQED and sign up for Ed100 if you haven’t already.

Tags on this post

Change Media Student voice Technology in educationAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Michelle Parker is the Executive Director of Education at KQED, an NPR and PBS member station in San Francisco serving the nine county Bay Area. She’s worked in the education and arts sectors her whole career. Her three children attended San Francisco Unified School District K-12.

Michelle Parker is the Executive Director of Education at KQED, an NPR and PBS member station in San Francisco serving the nine county Bay Area. She’s worked in the education and arts sectors her whole career. Her three children attended San Francisco Unified School District K-12.

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .