Education, the economy and effort

Time to look down

When it comes to funding for education in California, 2022 was simultaneously the best year in history and the stingiest in decades. Districts are preparing for worse.

In This Post

Global context: How does America’s commitment to K-12 education compare to other countries?

State context: How does California’s commitment to K-12 education compare to other states?

Economic return: How does spending on public education pay back?

Early education: How does California’s commitment to preschool compare to other nations and states?

Sufficiency: How much is needed?

The budget for 2022-23 was enacted in the context of a stock market boom. Capital gains realized by some of the state’s top taxpayers fueled a big increase in the state budget. Under the constitutional rules that voters created by passing Proposition 98 in 1988, a significant portion of the increase automatically flowed to education. The fiscal tide rose, lifting California’s schools to the highest level of funding per student in state history.

But even as spending on education rose, in a sense it also fell.

For education, it was the lowest funding effort in decades.

As this post will explain, even at its peak California invested less economic effort to fund schools than in any year since 1984, and less than most other states. In terms of its economic commitment to fund education, California is structurally stingy, even when the stock market rains money.

National context: America is typical.

Compared to other countries, America displays unremarkable effort to fund basic education.

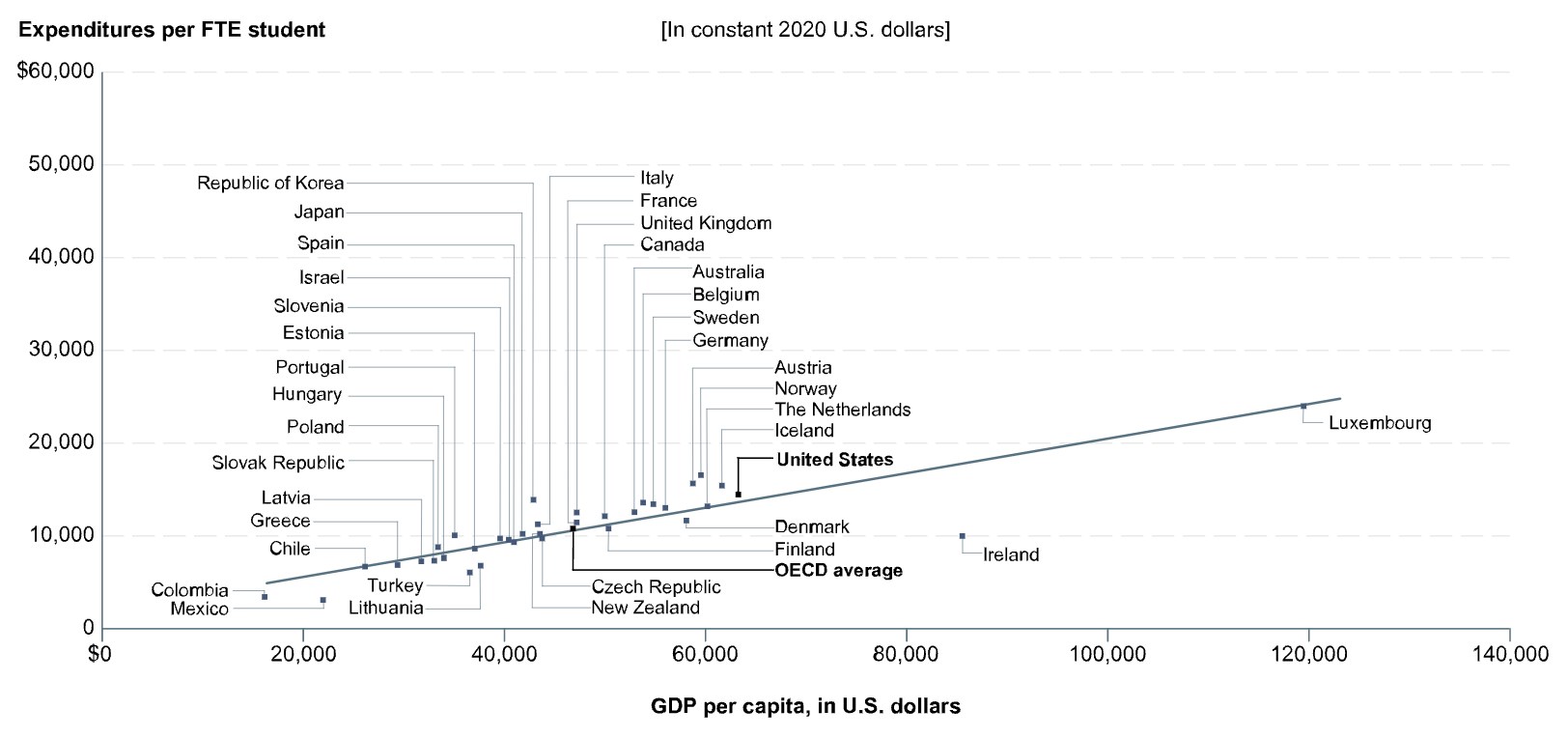

Among developed nations, the size of each country’s overall economy tends to correlate pretty tightly with the amount spent on public education. Countries with bigger economies spend more money on public education. Countries with smaller economies spend less. But the proportion tends to be fairly consistent, as the chart below illustrates:

Source: OECD, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Online Education Database. Retrieved October 7, 2021. See Digest of Education Statistics 2021, table 605.10.

The percentage of the economy spent on primary and secondary education is a relative measure of education funding effort. In 2018, the average nation in OECD spent roughly 3.1% of its economy on public primary and secondary education. Some countries (like Korea, Austria and Norway) invest relatively more effort to support education, while others (like Mexico, Ireland and Turkey) invest relatively less effort. As OECD calculates it, nationwide spending on public K-12 education in America was about 3.2 percent of the U.S. economy, roughly in line with international norms.

Bottom line: America’s overall average commitment to public K-12 education is basically ordinary in comparison with other developed nations. But the story doesn’t end there.

California state context

California’s effort to fund K-12 education is low compared to other states

In the United States, public education is governed and funded primarily at the state and local level. Funding per student varies at least as significantly among the states as it does among nations. Most of the variation at the state level is in line with costs, but some states (like New York and Vermont) invest more effort to fund public education while others (like Florida and California) spend less effort.

The level of effort to fund public education has eroded in many states over time. In 1970, the average US state invested effort to fund public K-12 education at a level of 4.0% of its economy. As the chart below shows, funding effort since 1970 has declined in many states, including California (the orange line). The US Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated that the average US state’s economic effort to fund public K-12 education in 2018 was 3.4% (slightly higher than the OECD estimate).

In 2021, California’s economic effort to fund public education dropped to 0.0299, its lowest level since 1984.

Public school in economic context

Primary and secondary education is a significant long-term investment in each student. Over the course of 13 years of K-12 education, an average student in the state of New York will have about $390,000 cumulatively invested in them. In California, the cumulative investment will be about $220,000.

Yes, education costs a lot.

Does an economy that invests more on K-12 education grow faster than an economy that spends less on it? A full exploration of this important question is beyond the scope of this post, but the short answer is yes, yes, yes, probably (so spend confidently but responsibly).

Of course, it takes decades for a social investment of this scale to pay back, and not all of the payback is in the form of money. Wise investment in effective universal education helps create the conditions for lots of good things, from peace to profits. Underinvestment or ineffective spending on education creates conditions for inequality and social problems. Either way, it can take decades for the effects of education to show up in measurable ways.

The figures above relate only to the 13 years of public K-12 education, which has become an outmoded way of thinking about the scope of a 21st century public education system. Early education is vital to successful learning. Most developed countries have simply added it to their system so that public education begins earlier than Kindergarten. America lags in this rather obvious extension. The average nation in the OECD invests 0.7% of its economy on educating and caring for children through age 5. The comparable figure for the United States is 0.3%.

As usual, there is a lot of variation among US states. Many states have publicly-funded early education programs, but with varying scope.

In California, school enrollment isn’t required for students until age six (first grade). Prior to first grade, families may enroll their children in kindergarten — and roughly 93% do so. Before kindergarten, in most parts of California families may enroll their kids in public preschool, known as Transitional Kindergarten (TK).

Preschool education correlates with wealth — that is, kids from better-off families are more likely to enrolled than those from poorer ones. By fall 2025, all four-year-olds in California will be eligible for public preschool, but it won’t be mandatory. The usual patterns that drive inequality are likely to apply.

Kids who have had a solid preschool education are more likely to show up to kindergarten with their wiggles worked out, ready to learn along with others. Given the evidence about the positive impacts of early education, and the harm caused by making early education less than universal, it doesn’t seem like it should be a hard choice.

How much funding is enough?

Each student learns from experiences and curricula that activate their minds.

Facing all kinds of obstacles, public school systems have to deliver for each student through processes and programs that cost money and take time. To work, programs have to be sustained financially with support from parents, communities and taxpayers. That’s hard to do.

Learning tends to work best when it happens in a strong relationship with an inspiring, well-prepared teacher. People with the skills and personal qualities to inspire students at scale have lots of professional options. California’s education system depends on recruiting, training and retaining great teachers at massive scale. It costs money.

California’s public school systems are funded each year based substantially on rules that voters wrote into the state constitution in the 1970s and ‘80s. Oversimplifying rather heroically, schools get about 40% of the state General Fund, plus a share of property taxes at the rate set by Proposition 13. Some additional money comes from federal taxes. Some has come from statewide measures passed by the legislature and confirmed by voters. (Some of that is temporary: billions will expire in 2030.) Very little comes from local taxes.

Even in the best year for California’s education budget in decades, funding per pupil barely reached the national average. School districts struggled to find qualified candidates that want to teach in the state’s overflowing classrooms.

Californians should be alarmed by these conditions. Even in the best education budget conditions of the state’s recent history these shortfalls persisted and funding effort fell. The future prosperity of California depends on the health and education of its people.

Education is the Golden Goose of the Golden State. Chronically underfeeding it is a risky plan. Education is expensive, but so is the lack of it.

Tags on this post

Budgets Funding Economic growth EffortAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Albert Stroberg March 7, 2023 at 10:58 am

Jeff Camp - Founder March 8, 2023 at 11:00 am