How is the education budget for 2023-24 being created?

California's budget process, squeezed into one blog post for 2023

Every year, California creates a budget for public education. How does that process work? Who creates and influences it? When are the decisions made? How can you get involved and have an influence?

…and how has a declining stock market changed things in 2023?

Despite lower projected state revenues, funding for education inches up a bit in the Governor's budget proposal for 2023-24. We’ll get to that in a moment — including the impact of inflation on these numbers– but first let's back up a little.

Budget basics

The state of California operates on a fiscal year that begins in July. Each January, the governor proposes a state budget based on a forecast of how much the state will take in through taxes deposited into the state's General Fund. (Some additional, restricted money also goes into Special Funds.) Under public scrutiny and comment, the Governor’s proposal is formally revised in May. A budget bill must be passed by the legislature and signed by the Governor by June 30.

Multiple taxes make up the state budget. The mix of sources has changed over time.

When the stock market sneezes, California’s budget gets sick.

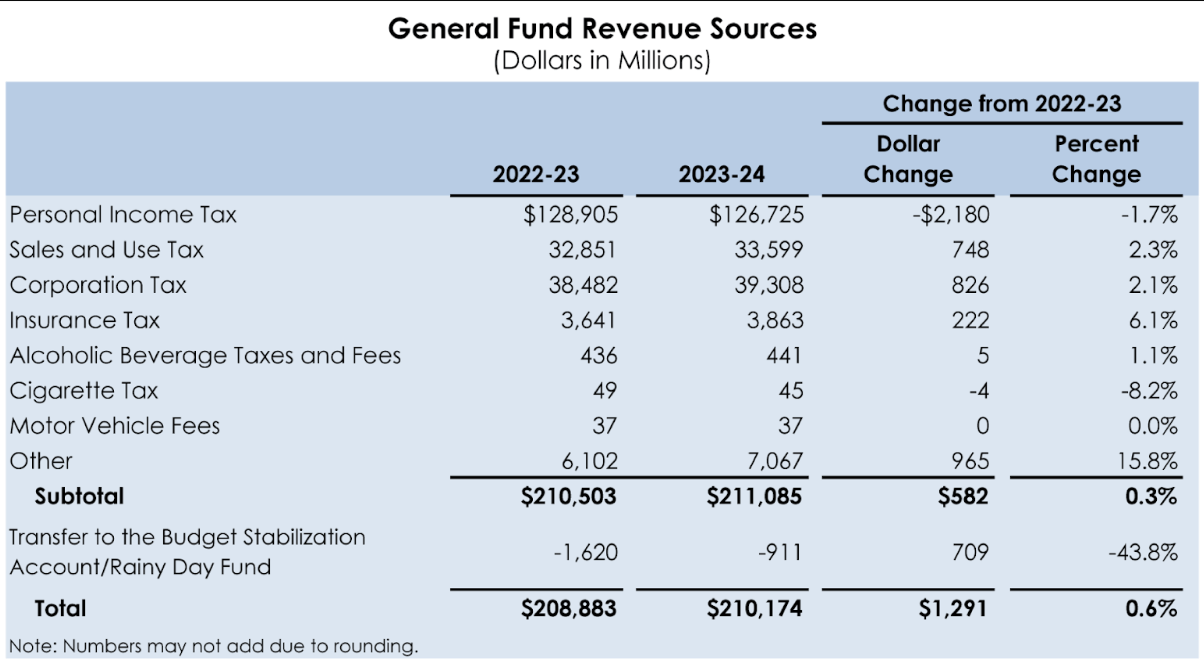

The table below shows how General Fund revenue sources are expected to change in the year ahead. Most revenue sources are expected to increase, but personal income tax receipts (the biggest slice of the pie) are expected to fall. Because when the stock market sneezes, California’s budget gets sick.

General fund expenditures

The state budget supports a wide variety of services to meet the broad needs of the state. The graphic below shows the proposed expenditures from the General Fund for 2023-24. K-12 education is the state's largest investment, followed by health and human services and higher education.

Budgets are reflections of values. Lower anticipated revenue forces the Governor and the legislature to make difficult decisions about spending priorities. The table below shows the proposed budget funding decisions. Health and Human Services receive the biggest increase followed by K-12 education. Many other functions take a big cut.

How is the education share of the state budget determined?

The portion of the state general fund that goes to K-12 schools and public community colleges each year is determined by formulas that voters enshrined in the state constitution by passing Proposition 98 in 1988.

Oversimplifying a lot, this formula usually requires that about 40% of the state General Fund should go to education. The formula includes many factors, including how well the economy is doing, whether there are more or fewer kids showing up to public school, and changes in the cost of living.

In theory, the legislature can allocate more of the general fund to education than this formula requires. In practice, it rarely does. The governor's proposed budget for 2023-24 allocates about 38.6% of the general fund to education based on the requirements of the Prop. 98 formula.

Per pupil funding changes this year

Ready for something nerdy? Enrollment is declining, but the decrease doesn’t trigger a decrease in funding. Here’s why.

The Prop. 98 funding guarantee has three different tests to determine the level of funding. Two of those tests look at projected revenues and projected enrollment. But there is one other test that is based only on general fund revenue. This year the budget calculations use that test because it yields more funding. Thus, the percentage of General Fund revenues is not reduced to reflect declining enrollment, which increases per pupil funding. Yes, it's complicated. And also: Yippee? Or Whew, at least?

How is the money in Prop. 98 allocated?

The set of rules that allocate funds from Prop. 98 to school districts is the Local Control Funding Formula (known as LCFF or “the LCFF”). Most education dollars are allocated to districts based on the number of students who show up to school and the characteristics of those students. Under LCFF, districts receive extra funds to support students who are low income, in foster care, and/or learning English. (Read Lesson 8.5.)

|

Education funding by the numbers, 2023-24 Governor's Budget |

|

|---|---|

Total funding |

$78.7 billion General Fund and $49.8 billion other funds for all K-12 education programs. |

K-12 per-pupil funding |

$17,519 Proposition 98 General Fund, the highest level ever. It's an increase of $526 per pupil over 2022–23 funding levels and $23,723 per pupil when accounting for all funding sources. (Note that the Proposition 98 fund includes money from local property taxes in addition to the state general fund.) |

LCFF cost-of-living adjustment |

8.13 percent increase. When combined with growth adjustments, this increase will result in $4.2 billion in additional discretionary funds for local educational agencies. |

What additional sources fund education?

Although the state General Fund accounts for most of the funding for California's K-12 education system, there are two other significant sources to know about: property taxes and federal funds.

Property taxes. Decades ago, local property taxes were the main source of revenue for public schools. Nowadays, they usually amount to somewhat less than a quarter of the money for K-12 education, but as we explain in Ed100 lesson 8.3, every year is different. Property taxes for education are not part of the state budget, but estimates are included in the accounting of Proposition 98 budget figures.

Federal funds. Federal funds usually contribute less than a tenth of the cost of schools in California, but these are not normal times. California has received $15 billion in federal Pandemic relief funding for things such as mental health and trauma needs, learning loss, safe return of all students in-person, full-time school and the teacher shortage.

Local funds like parcel taxes and donations aren't considered in the state budget process.

Lower state revenues: $24 billion budget problem

California faces what is euphemistically called a “budget problem” — a deficit of about $24 billion. The problem is mainly attributable to lower revenue estimates.

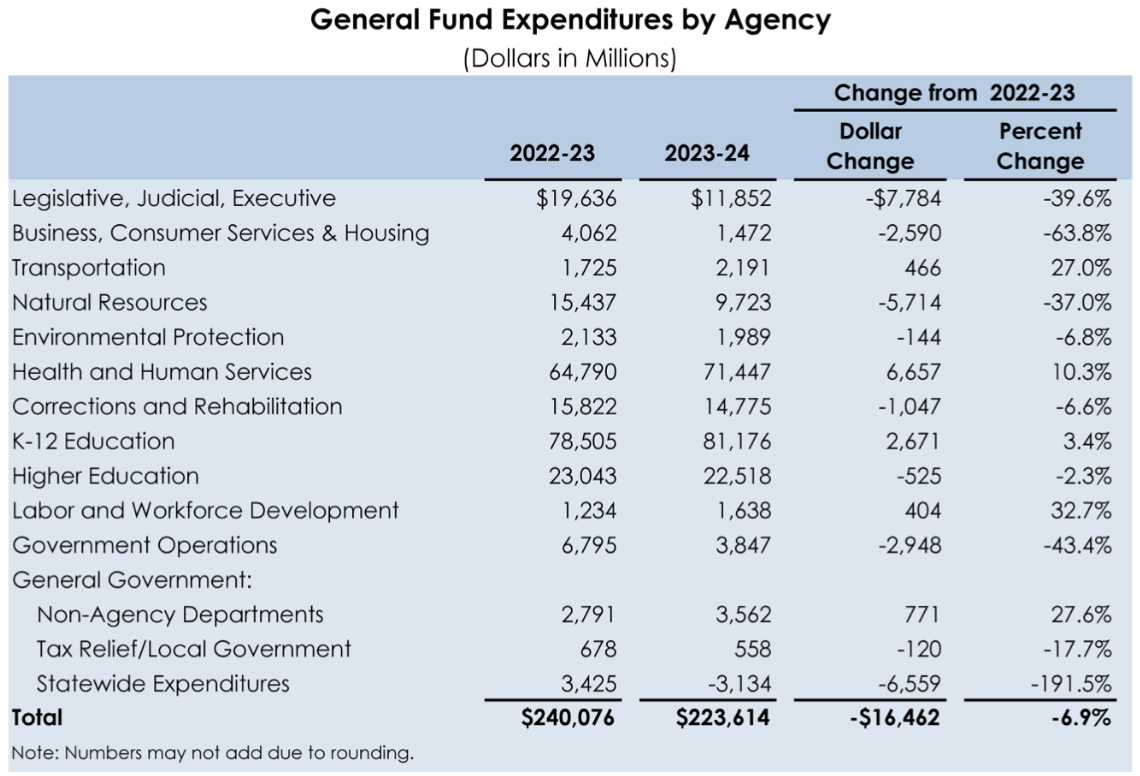

Stock options and bonus payments (or the lack thereof) greatly influence the taxable incomes of California's wealthiest taxpayers, who generate a huge fraction of the state's tax revenues. In announcing his 2023-24 budget proposal, the Governor led with an explanation of the volatile nature of state tax revenue in California. Taxable capital gains vary wildly from one year to the next, producing a state revenue pattern that he compared to an EKG:

The Governor’s Budget forecasts that General Fund revenues will be $29.5 billion lower than the last year’s projections. California now faces an estimated budget gap of $22.5 billion in the 2023-24 fiscal year. (The California Legislative Analyst Office (LAO) forecasts a slightly larger deficit of $24 billion. This is a remarkable level of agreement.)

California’s constitution requires that the state budget must be balanced each year. Unlike the federal government, the state may not run a deficit. To balance the budget, the Governor proposes to delay, reduce, and shift funding as detailed here based on an analysis by the LAO here.

A drop in the projected Prop. 98 guarantee does not necessarily mean schools get less money.

Every budget year the state projects the level of Prop 98 funding for the next three years. Sometimes it’s right, but sometimes the economy changes. Let’s say you have revenue of $5 dollars this year and estimate that it will be $10 next year. But your estimate is wrong. You will only have revenue of $8 dollars. That’s $2 short, but you still earn more next year.

That’s what happened to the state Prop. 98 guarantee. Based on estimates of lower General Fund revenue, the Proposition 98 funding guarantee is reduced from $110.4 to $108.8 billion for 2023-24. That's $1.5 billion less than expected, but still higher than last years’ recalculated guarantee of $107 billion. (See graphic below.) By the rules of Prop. 98, there is still more money for schools.

The Legislative Analyst explains that although the minimum guarantee drops, funding is available for spending increases due to the expiration of one‑time initiatives and lower‑than‑anticipated program costs. “The Governor’s budget includes a net of $6 billion in new Proposition 98 spending—a total of $7.4 billion in spending increases, offset by $1.4 billion in spending reductions.”

According to LAO projections, the General Fund portion of the Prop. 98 guarantee will grow by $16.7 billion from 2022‑23 to 2026‑27.

What does inflation do to school funding?

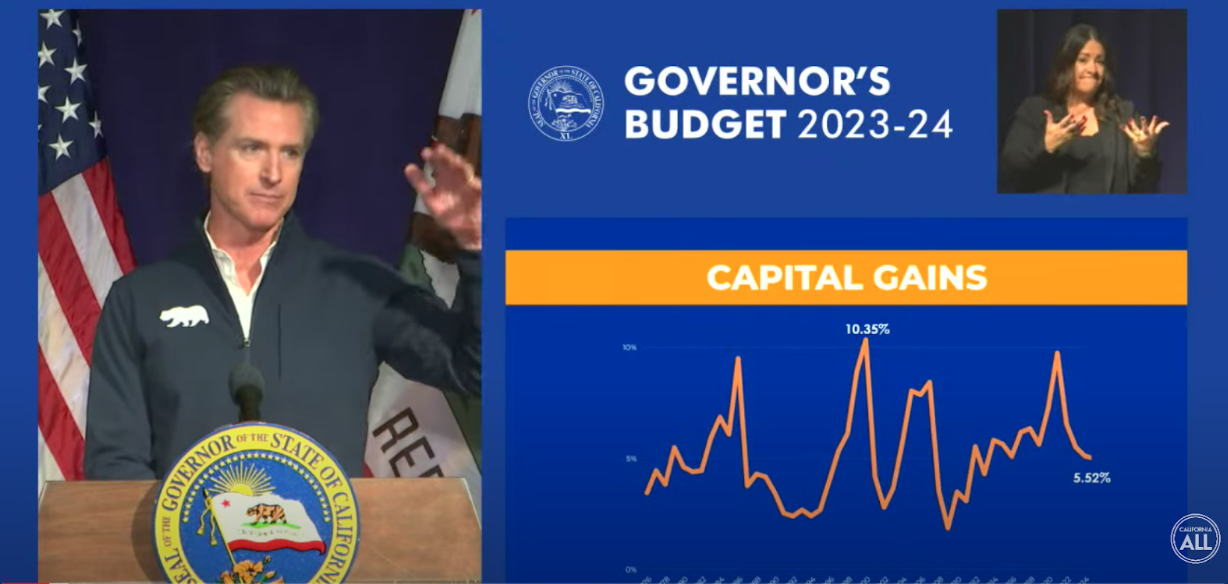

There are two major ways to look at the growth of Prop 98 funds over time. The budget presents it as in the chart below, highlighting the dramatic increase in dollars of funding over time.

The other way to look at historical budget data is to consider it in context. Dollars in a budget are only good for what they can buy. Over time, inflation acts like a curved rear-view mirror: it makes historical numbers seem small and recent numbers seem big.

When adjusted to account for the change in purchasing power, Prop. 98 funding per student peaked in 2021-22… and isn’t all that different from 30 years ago:

The Legislative Analyst reports that “between 2019-20 and 2021-22, the minimum guarantee grew by $31.3 billion (39.5 percent)—the fastest increase over any two-year period since the passage of Proposition 98 in 1988. The drop in 2022-23 erodes only a small portion of this gain.”

|

2023-24 California Education Budget Highlights |

|

|---|---|

LCFF Cost of Living Increase (COLA) |

To help schools deal with inflation, the Governor's proposal contains a significant LCFF cost of living increase – 8.13%. |

Equity Multiplier (new) |

The Governor’s proposal includes $300 million to create and fund an equity multiplier on top of LCFF. The money would go to the highest-needs schools in the state, benefiting the many low income, Black and Hispanic students who attend those schools. |

Non-LCFF Cost of Living Increase |

Provides a cost-of-living adjustment of 8.13 percent for categorical programs that remain outside of LCFF, including Special Education, Child Nutrition, State Preschool, Youth in Foster Care, Mandates Block Grant, Adults in Correctional Facilities Program, Charter School Facility Grant Program, American Indian Education Centers, and the American Indian Early Childhood Education Program. |

Transitional Kindergarten (TK) |

Adds $690 million for the second year of transitional kindergarten expansion. This will increase access to all children who turn five between September 2 and April 2 (approximately 46,000 children). Another $165 million supports the addition of one additional certificated or classified staff person in TK classrooms serving these students. The budget delays some commitments to fund facilities for full-time kindergarten/pre-K |

Child Care Availability and Affordability |

Over $2 billion annualized to expand subsidized child care slot availability. |

Universal School Meals |

Adds more than $1.4 billion to reimburse school meal costs and ensure all students will have access to two free meals each day if they want them. |

Literacy |

Adds $250 million in one-time support for the Literacy Coaches and Reading Specialists Grant Program. $1 million one-time to create a Literacy Roadmap to help educators navigate literacy resources and effectively and efficiently use them in their classrooms. |

Teacher Shortage |

The proposed budget follows up on multi-year investments made in 2021 and 2022 to recruit and retain high quality teachers. This includes $1.5 billion in one-time funds over five years to provide local educational agencies with training resources for classified, certificated, paraprofessional, and administrative school staff in specified high-need topics. |

Reversing Opioid Overdoses |

Adds $3.5 million in ongoing Prop. 98 funds for all middle and high school sites to maintain at least two doses of naloxone hydrochloride or another medication to reverse an opioid overdose. |

Arts |

$100 million one-time funds from the Proposition 98 General Fund to provide high school seniors with access to cultural enrichment experiences across the state. This comes to roughly $200 per 12th grade student enrolled in California public schools. Funds might be used for museum visits, access to theatrical performances, or other participation in extracurricular art enrichment activities. Prop. 28 (passed in November 2022) invests about $1 billion each year to support arts education. The budget cuts $1.2 billion from the one time Arts, Music, and Instructional Materials Discretionary Block Grant included in the 2022 Budget Act. |

The budget process ahead

Throughout the first half of the year, committee hearings examine both the budget itself and education bills that might have an impact on the budget. Each of these pathways is a little different. (The California Budget & Policy Center, a non-profit organization, does a great job of explaining the distinction between these two paths.)

By January 10, the Governor officially kicks off the budget process by proposing a budget with support from the state Department of Finance. Budget committees in the Senate and Assembly consider the Governor's proposed budget as a whole. Subcommittees in the Senate and Assembly separately examine the proposed budget for education. These hearings are open to the public. When agendas are set, you can find them online.

After the Governor releases the proposed budget, advocates react, shoring up support for the parts they favor and scrambling to make adjustments.

By May 14, the Governor releases a revised budget, reflecting more up-to-date financial information. (You guessed it, it's called the May Revise). Separately, the Budget Committees of the Senate and Assembly also each adopt their version of the budget. A conference committee irons out differences between these versions.

By June 15, the Senate and Assembly leaders huddle with the Governor to hash out the final details and pass a balanced budget by a majority vote of both houses. If the process gets stuck and they don't pass a budget on time, legislators are not paid, based on an initiative passed in 2010 after a series of budget delays.

On July 1, the state begins the new fiscal year. Between the passage of the budget by the legislature and July 1 the Governor may cut specific expenditures using line-item vetos. This is rare. In 2020 it was used once.

Education policy bills: A parallel process

At the same time as the main budget bills are in the works, the Senate Education and Assembly Education committees consider policy bills that affect education. Some policy bills approved by these committees involve money. If a bill requires significant money, it must survive passage through the Senate Appropriations or the Assembly Appropriations Committee. Many bills die in these committees because the cost is too high.

The budget bill is adopted by July 1, but education policy bills continue the legislative process through the summer. Similar to the federal process, after a bill passes one house, it must then go to the other for consideration. The adopted budget may be revised a bit, with the Governor's approval, to include funding associated with these adopted bills. In 2022, the legislature passed about $22 Billion in additional spending in this way; about half received the Governor's signature.

How you can get involved

That’s why you are reading this, right? You want to know how you can get informed and have some say in the budget process.

Get Informed. Throughout the development of the budget, the Legislative Analyst's Office provides detailed information and analysis. You can sign up to be notified whenever there is a new report. Separately, the California Department of Finance offers information on the current Governor's budget, as well as budget information from past years.

As bills work their way through the legislative process, you can find information about them on the state's Leg Info page (it's pronounced "ledge info").

Support an organization's voice. Some education organizations take positions on bills under consideration, and may or may not make those positions public. For example, you can find current positions of the California State PTA online. Other vocal advocates include the California Charter Schools Association and the California Teachers Association.

Hear Carol's radio interview about how to be heard.

Participate in public comment. The legislative process includes opportunities for public comment. Agendas are posted online. The California Senate and the California Assembly provide live webcasts of legislative hearings. The Senate and Assembly committees have staff members who take their work seriously and may be able to help provide more information about legislation.

Meet with your legislator. Legislators welcome contact with their constituents, especially this year because the census is causing many district boundaries to change. Why not set up a meeting with the office of your legislator to discuss an issue you care about? Frequently, you will be directed to the staff person who is responsible for education issues.

Tags on this post

Budgets FundingAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .