Using School Time Creatively

Tick, Tick, Tick...

The most valuable resource in education, as in life, is time. A school year consists of about 1,000 hours of school time. In 2020 many schools and districts will have a rare opportunity to think afresh about how to use those hours.

Schools structure those 1,000 hours in different ways to make the most of them. Traditionally, middle schools and high schools have divided the time into periods of more or less equal duration, with students moving from class to class on a formal schedule. In the days before accurate time was easily knowable on every phone, schools used bells, buzzers or loudspeakers to keep everyone in sync. Many schools still call it a bell schedule, even if they have stopped using audible signals to drive the pace of the day.

A Wrinkle in School Time

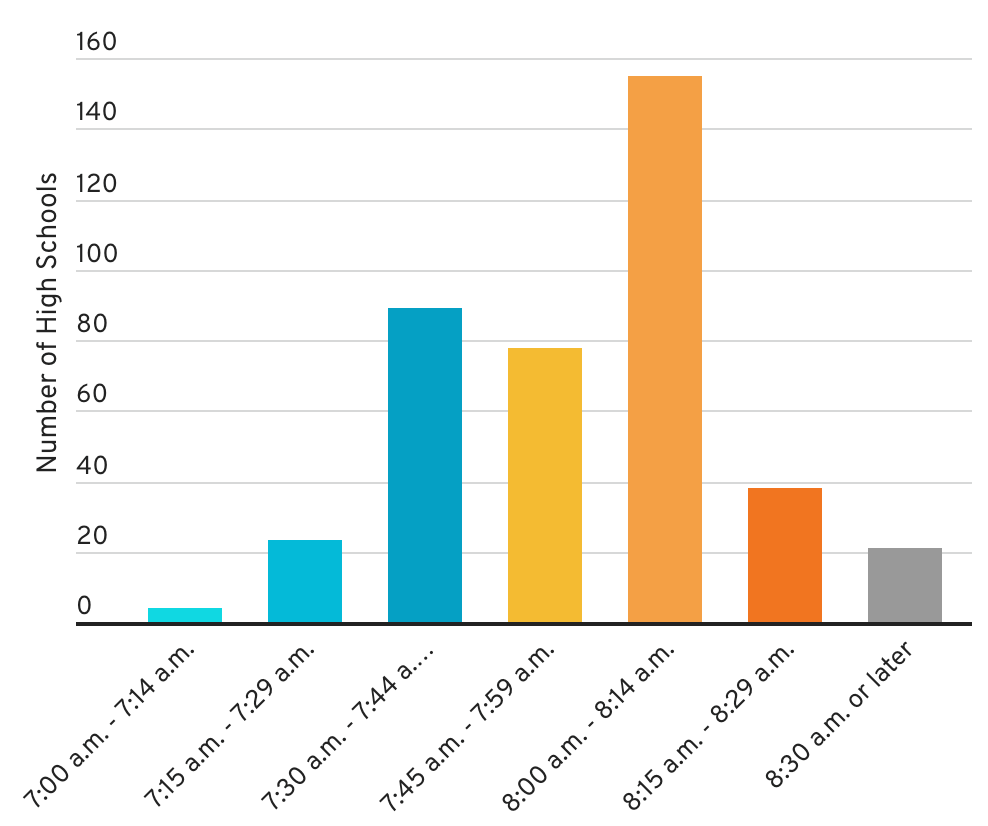

In 2019 the California legislature passed a law that will require perhaps nine out of ten high schools in the state to rethink their schedule. Responding to research about the educational and health benefits of sleep, the law will require middle schools to begin no earlier than 8:00 am and high schools to begin no earlier than 8:30 am. In most districts, the law will go into effect in the 2022-23 school year.

The vast majority of California high schools will have to change their schedule. Starting in 2022, most high schools must begin no earlier than 8:30 am. Source: CalMatters research / California high school bell schedules. (Click for more)

The vast majority of California high schools will have to change their schedule. Starting in 2022, most high schools must begin no earlier than 8:30 am. Source: CalMatters research / California high school bell schedules. (Click for more)

Schools could respond to this change by simply moving the start and end times of the school day. But that would be to miss an opportunity. The start and end time of the school day must change, but other aspects of the schedule could be changed. This is an unusual chance for a conversation about how the school uses time to support the needs of students and teachers. Would longer class sessions lead to deeper learning? Is the schedule effectively supporting faculty collaboration, for example to implement the Next Generation Science Standards? Does the schedule meet the needs of English learners? What are the options?

Mental Blocks

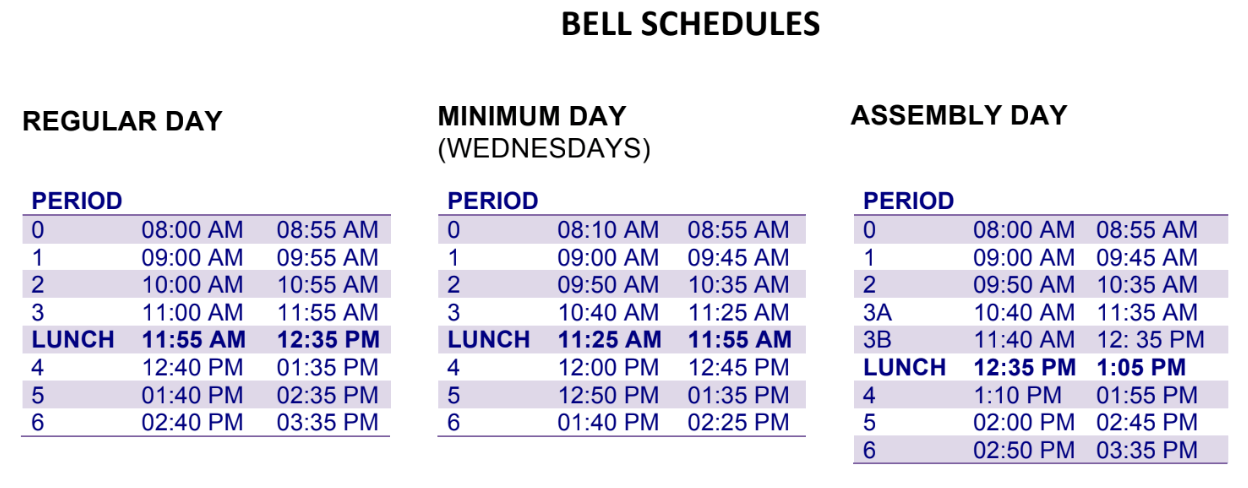

In traditional high school schedules, classes are of uniform length (on the order of 45 to 55 minutes) and students attend the same six or seven classes every school day. The schedule is broken into numbered periods. (For example, first period might run from 8:00 to 8:55, as in the example below.)

Some middle schools and high schools use a different approach, organizing time into longer stretches, generally called blocks. In block schedule models, students do not necessarily attend class on each subject every day.

Block schedules are not new, and a lot has been written about them, but research about them is scant. Research questions are easiest to answer when they are narrow; because each school's implementation is unique and the aims of school schedule design are diffuse, it is difficult to reach generalizable conclusions.

Mega blocks: Quarter and Trimester Systems

The schedules that depart most dramatically from tradition are sometimes called 4x4 schedules, but it might be helpful to think of them as quarter systems. In this approach, students take only four subjects at a time, instead of the usual six. Daily class sessions are longer — perhaps 90 minutes each. A class that meets for a full year in a traditional schedule might only meet for half of the year in a 4x4 model. Some California schools use a schedule similar to this model, but modify it to comply with the state's PE requirements.

A related (and fairly rare) approach is the trimester schedule, which breaks the school year into three trimesters instead of two semesters of four quarters. In this model, again, students take fewer classes at a time.

A common criticism of both quarter systems and trimester systems is that they have to move along quickly. If students fall behind, it can be hard to catch up.

Long Block Schedules

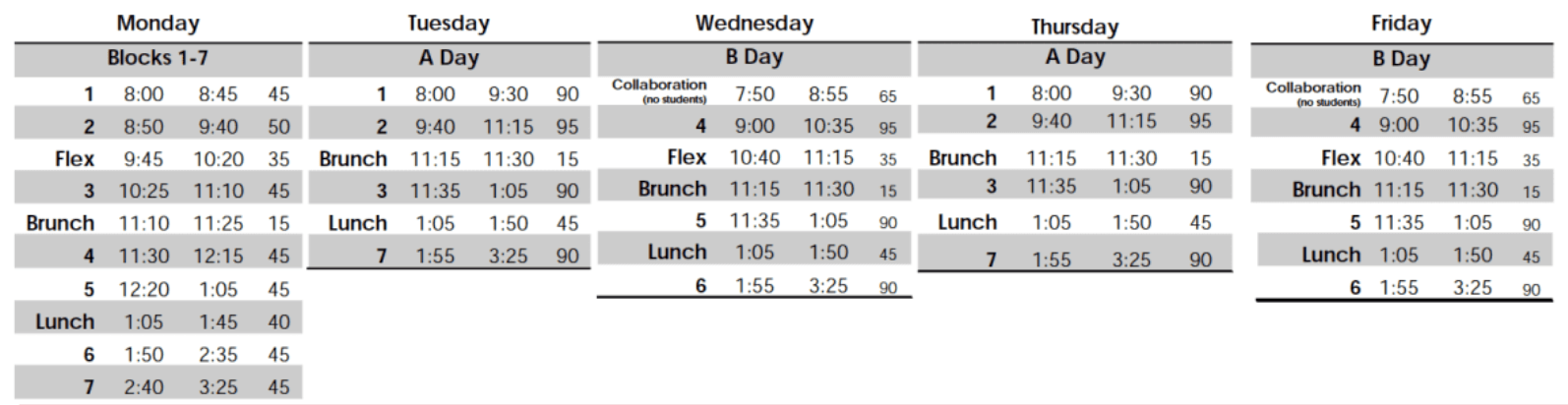

Not all block schedules break so thoroughly with tradition. For example, an approach sometimes called a rotating block schedule (or A/B schedule, or simply a "long block" schedule) keeps the general shape of the traditional model (six or seven classes per semester) but extends class lengths on certain days of the week.

For example, at Fremont High School in Sunnyvale classes are "traditional" on Mondays — that is, students attend classes on all of their subjects for about 45 minutes each. On Tuesdays and Thursdays (the "A" days) students attend half of their classes for about 90 minutes each. On Wednesdays and Fridays ("B" days) they attend the other half of their classes for about 90 minutes each. They also meet with teachers on a reservation basis (a practice they call flex scheduling.)

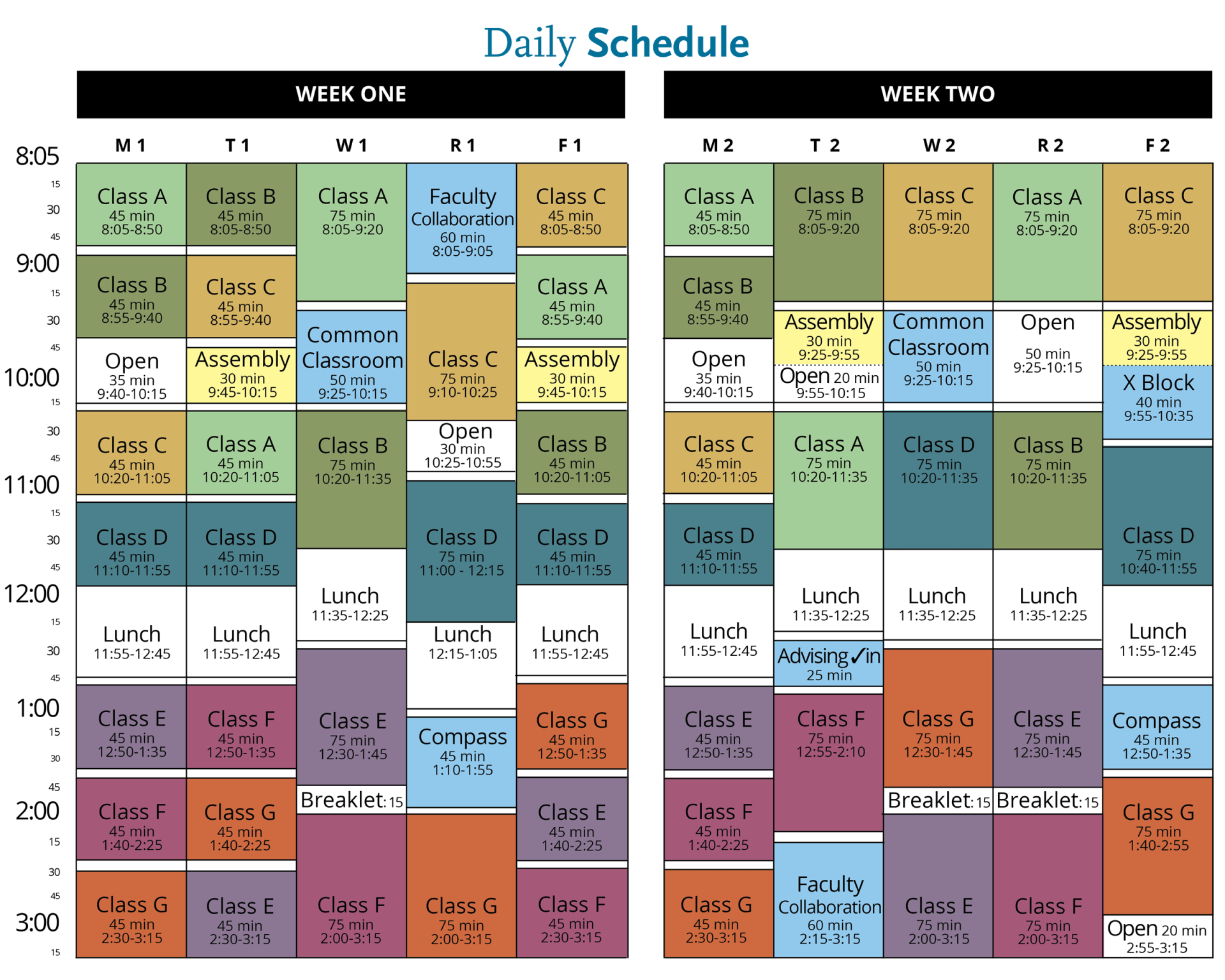

There are many, many variations. For example, College Prep School, a private school in Oakland, California, uses long blocks in a pattern that varies on a two-week cycle. The schedule includes time for assemblies twice each week. As with Fremont, this schedule sets aside time each week for faculty collaboration.

There tends to be no shortage of ideas when schools crack open their schedule design for reinvention. Some schools align their schedule with local community colleges to encourage dual enrollment. Others add blocks to explicitly encourage students to pursue interests online.

Who likes block schedules?

Schedules that include long blocks tend to enjoy enthusiastic support from science teachers and art teachers because long blocks allow time for students to become immersed in projects and experiments that take time to set up and clean up. For history, math and English teachers, long blocks require a different kind of planning. To use them successfully, teachers have to move beyond a lecture-and-test approach, using time for discussion and peer review. If teachers don't know what to do with a long block, the results might be bad.

Some research suggests that block schedules may improve the quality of relationships between teachers and students, perhaps because interaction is less rushed. In block schedules, students lose less of their time transitioning between classes, and there is some evidence that this correlates with fewer discipline issues.

Block Talk

Modifying the school schedule involves change — which almost by definition means that some people will hate it, at least initially. Some of the objections might be reflexive, but others will be important and not necessarily obvious. (For example, some changes may require changes or waivers in the teacher contract.) Schools that successfully navigate the shift from traditional scheduling to block scheduling tend not to rush it.

Many schools that consider a change in the school schedule begin with a task force to study the options and collect ideas and concerns.

For example, San Francisco Unified School District has been working with the school community to redesign schedules for middle schools with the goal of expanding access to arts, computer science, health and world languages for all middle grade students. Block scheduling on a trimester model is a key element of the draft plan. The redesign also envisions additional professional collaboration and development opportunities for teachers.

Teachers will need time to plan how they will use long blocks differently than short ones. Opening a discussion about the school schedule will probably lead to conversation about the school calendar, too.

But this is an interesting moment. Some amount of change is unavoidable: California's new laws about school start times require it. If school communities start conversations now in a way that invites broader thinking, it could lead to important insights about how to help students and teachers improve their work together.

Is your school considering a shift to a different scheduling model? Know of a great resource to prompt discussion? Please share it!

Tags on this post

All Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .