Most kids find their way to adulthood without breaking bad, but some kids cause trouble. What is the role of public schools in heading off costly outcomes?

In This Lesson

Are school dropouts random?

How much does a dropout cost the public?

What is the cost of a year in prison versus a year in school?

What is social mobility and how can schools advance it?

How much is a college degree worth?

Does education make up for gender gaps in pay?

Why do people focus on the problems?

Why do segregated schools fail?

▶ Watch the video summary

★ Try the chapter Discussion Guide

An old expression cautions that “one bad apple can spoil the whole barrel.” When making cider, the remedy is simple: throw out the bad apples and forget about it. In education, the solution isn't easy at all, because kids aren't apples. We are all in the cider together.

Universal public education is society's biggest, most personal investment in the future. Schools are meant to support the progress of each student from early childhood through early adulthood. This investment is not purely altruistic. Collectively, we are all better off when kids find their way to adulthood without too much drama. On average, they do — but kids aren't averages.

The problem with averages

Education statistics often emphasize averages, such as average test scores or graduation rates. These figures can conceal a lot. For example, imagine the average wealth of people at a Starbucks. Randomly, Bill Gates walks in. The average wealth in the store goes up, but no one has made more money.

Obviously, Gates is an outlier in this example. A statistician would discard him from the average, or calculate the median to reduce the distortion. But the big point is that statistics can help tell a story only with the benefit of context. Each of us is a story if you look close enough.

Overall, education tends to make a big difference in the economic conditions of living. The chart below shows average earnings of adults at various levels of educational completion. Generally, more education is connected to more income.

This pattern is very stable. Year in, year out, more education is connected to more income.

"Dropouts" are not random

Let's leave the coffee shop and return to education. The classic symptom of educational failure is a student who misses so many days of school that they just stop coming. Students in this position are not random — disproportionately, they tend to be African American and Latino, especially from low-income families. (Persistent patterns of differences in educational attainment by ethnicity, income, or gender are known as achievement gaps, a subject we take up in Lesson 9.6)

The social costs are real and high

Educational failure is expensive. Low educational attainment is correlated with social costs including unemployment, poverty, homelessness, crime, and poor health.

A small increase in the high school graduation rate translates to billions of extra dollars.

When children don’t get the education they need, who loses? The answer is that everyone does. The costs of failure are enormous. Scholars have tried to quantify them in different ways:

- Billions. The Civil Rights project at UCLA collects research about the impact of dropping out. For example, a 2014 study estimated the social losses caused by high school dropouts costs the state of California $37-$56 billion per cohort. In addition to the costs, they estimated that the aggregate impact for California taxpayers is a loss of $11-$17 billion per class cohort.

- Invest in kids. A report from the perspective of law enforcement under the provocative title I'm the Guy You Pay Later summarizes the costs of failing to invest in high-quality education, noting that increasing graduation rates correlates strongly with decreased rates of serious crime.

- Arrests. To examine how investment in the quality of public elementary schools affects crime rates, researchers at the University of Michigan followed the outcomes of two groups of students. They found that improving the quality of public schools is an effective way to reduce crime in the long term. Specifically, students who attended the better-funded elementary school were 15% less likely to be arrested by age 30 than those who did not.

- Property crime. In a 2021 study of national data by the University of California San Diego, researchers found that every $1,000 per pupil spent by a school district led to a 2.35% decrease in property crime.

- Achievement gaps. In 2009, as the nation was emerging from a recession, a report by McKinsey argued that the failure to address achievement gaps created what amounted to a permanent recession, causing the US economy to underperform by many billions of dollars.

- Missing connections. In 2011 the NAACP issued a report, Misplaced Priorities, to "track the steady shift of state funds away from education and toward the criminal justice system." In 2012, the White House Council for Community Solutions picked up the topic, commissioning research and coining the rather optimistic term opportunity youth for those aged 16-24 who are neither in school nor working. The term changed again, (to disconnected youth) in a series of reports from Measure of America, a project that compiles data about this costly, hard-to-serve segment. (See interactive charts.) In the aggregate, if America could persistently "connect" all young people as full participants in America's economy, our nation's balance sheet would expand on the order of about $5 trillion in taxes paid and direct costs avoided. That was trillion, with a "T," in case you missed it.

Prisons are incredibly expensive

A year of prison costs about seven times as much as a year of education. This ratio is even higher in California than in most other states, but the long-term rising costs of incarceration are a national challenge. Huge numbers of people are employed in the prison sector. Since 1970, expenditures for incarceration have grown faster than investments in education in every state:

Don't get confused by this statistic. Keeping someone in a prison for a year is much more expensive than educating a student for a year, but there are far more students than prisoners. Governments spend significantly more on their education systems than they do on their prison systems. In context, preventive investments are cheap — and worth it.

Taxpayers are not the only ones that benefit, of course, when a student persists in school. The biggest beneficiary is the student. The personal stakes of educational attainment are huge. According to year after year of data from the US Census Bureau, economic prospects improve dramatically with every additional year of educational attainment.

Education supports social mobility

Schooling advances social mobility, especially for those who need it most... but not equally for all.

Social mobility is the movement of individuals or families within or between social groups in a society, within a generation or intergenerationally. There are patterns. For example, Black boys are less likely to move up the social ladder. Using a data visualization from the New York Times, you can see some of the major patterns by making your own animated chart to explore the income mobility of different social groups. The Opportunity Atlas offers another interactive graph of child outcomes in neighborhoods across America.

These are patterns, not destiny. A study by Raj Chetty and others indicates that schooling, combined with efforts to achieve racial integration within neighborhoods and schools, can change social mobility and help minority children advance.

The College Board updates its ambitious Education Pays report every three years. Like clockwork, every report finds similar patterns: more education equals more money, better health, longer life, and more civic engagement.

As in the coffee shop, averages can lie. The Education Pays report does a good job of sketching the broad systematic variations. For example, at any given level of educational attainment, earnings for women and minorities lag behind earnings for white men.

Deficit-Attention Disorder

Because the social costs of failure are so high, it's easy to hyper-focus on the problems, ignoring the experiences of the young people who do quite well. Dr. Robert K. Ross, President and CEO of the California Endowment, calls this phenomenon "Deficit-Attention Disorder." In a 2017 report "The Counter Narrative," UCLA Professor Tyrone C. Howard flips the focus, exploring patterns of resilience and success among Black and Latino males in Los Angeles County and how they think about success from their perspective.

Social connections prevent failure

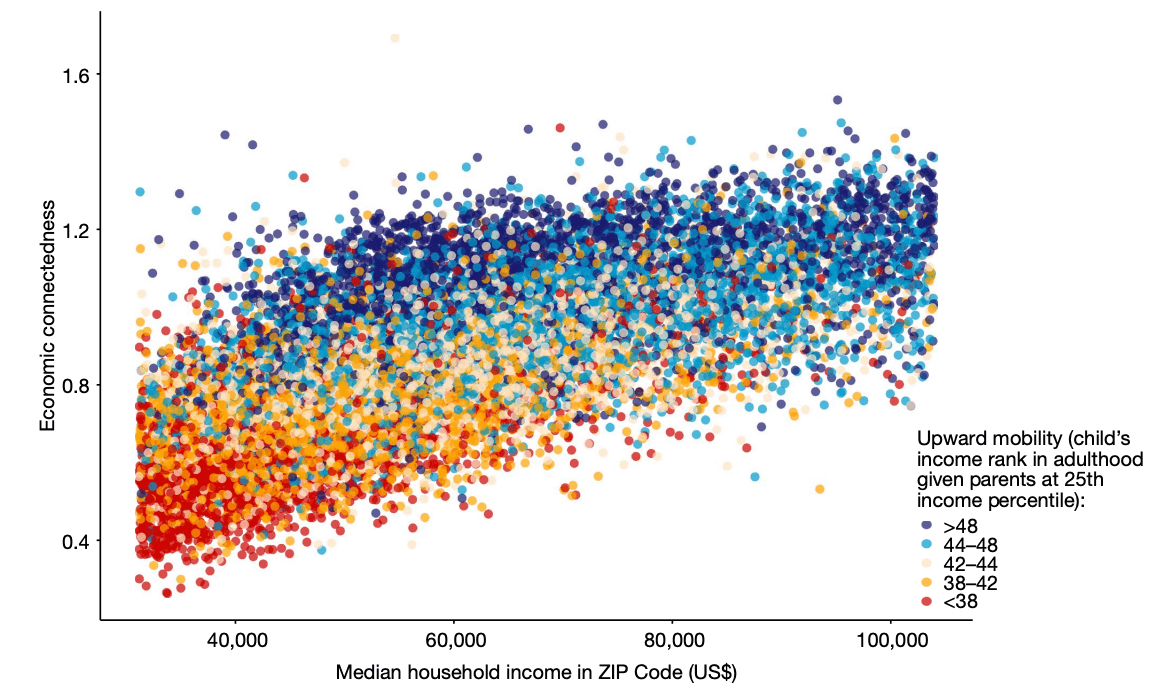

An important amount of what might appear to be education failure might be more usefully considered connection failure, according to important research by Raj Chetty. In a very large study of social networks, Chetty's team finds that social connections (or the opposite, social isolation), play a huge predictive role in lifetime economic outcomes.

People from zip codes that are economically connected tend to be upwardly mobile, according to Chetty's analysis.

Chetty's analysis implies that a critical role of schools should be to connect students across class lines. As we will examine in Lesson 5.1, most schools do the opposite.

Updated December 2024

Quiz×

CHAPTER 1:

Education is…

-

Education is…

Overview of Chapter 1 -

California Education

Are California’s Schools Really Behind? -

American Education

Are U.S. Schools Behind the World? -

Education and the Economy

Schools for Knowledge Work -

Educational Failure

The High Social Costs of Bad Apples -

Grade Inflation

Wishful Thinking and Cognitive Bias -

Are Schools Improving?

Progress in Education -

History of Education

How have Schools Changed Over Time? -

Purpose of Education

What are Schools For, Really?

Related

Sharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Sara Wolfe September 1, 2025 at 4:57 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder September 1, 2025 at 9:39 pm

Darla Williams June 4, 2025 at 8:01 pm

Yolanda Rodriguez May 10, 2024 at 8:37 am

David de Leeuw July 10, 2023 at 10:40 am

Jeff Camp - Founder July 10, 2023 at 11:33 am

Carol Kocivar June 13, 2022 at 6:31 pm

You can find a 40 state data analysis in the link below:

https://money.cnn.com/infographic/economy/education-vs-prison-costs/

Carol Kocivar June 13, 2022 at 6:31 pm

You can find a 40 state data analysis in the link below:

https://money.cnn.com/infographic/economy/education-vs-prison-costs/

Carol Kocivar June 13, 2022 at 6:31 pm

You can find a 40 state data analysis in the link below:

https://money.cnn.com/infographic/economy/education-vs-prison-costs/

Carol Kocivar June 13, 2022 at 6:28 pm

https://usafacts.org/data/topics/people-society/education/k-12-education/high-school-dropout-rate/

June 26, 2018 at 9:32 am

Sonya Hendren September 3, 2018 at 3:32 pm

Caryn September 10, 2018 at 9:29 am

francisco molina August 12, 2019 at 9:54 pm

Jeff Camp December 9, 2016 at 1:52 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder October 17, 2015 at 12:56 am

hannahmacl March 15, 2015 at 1:15 pm

If this suggests that the schools undertake responsibility for solving social problems, then I would say 'no'. However, if education would highlight and publicize and advocate, then 'yes'. In Los Angeles, issues such as inadequate housing, health challenges, and low wage jobs, exacerbated by inadequate transportation, none of which are within schools' purview, profoundly impact students' education.

Jeff Camp - Founder June 20, 2015 at 11:46 pm

jenzteam February 27, 2015 at 6:42 am

Jeff Camp - Founder June 20, 2015 at 11:43 pm

Brandi Galasso February 7, 2015 at 8:04 pm

Brandi Galasso February 7, 2015 at 8:00 pm

anamendozasantiago February 5, 2015 at 5:05 pm

Sherry Schnell January 22, 2015 at 9:23 am

Jeff Camp - Founder January 22, 2015 at 9:49 pm

Steven N June 20, 2014 at 3:00 pm

Social welfare & the poverty gap in education - can be met by more programs for those in most need. Will California local school boards insist on this outcome?

Michael Rebell March 7, 2011 at 7:28 am

Jenny N September 22, 2015 at 5:08 pm