How should students be counted?

The pandemic forces a new look at funding

Student attendance dropped dramatically in the pandemic, precipitating a twin crisis. The first is a crisis in learning: when kids miss class, everybody learns less. The second, less obvious crisis has to do with the way money flows in California’s education system. State school funding to school districts is based on how many students attend school, not how many are enrolled. No students in school, no money.

The butts-in-seats method of calculating attendance-based funding broke down during the pandemic. What did attendance mean? No one could attend school in person, and for a while California basically put the system on a kind of suspended animation, basing attendance numbers on prior years. That stop-gap relief has ended. Now the state is looking at more permanent strategies to address not only emergency attendance drops but also the slow pattern of declining enrollment in most parts of the state.

See California eBudget summary

Most state funding systems use enrollment, not attendance

California’s use of attendance as the basis for school funding is unusual. As of 2021, only seven states use this approach. Most rely on enrollment data, sometimes with adjustments.

Average Daily Attendance (ADA) is how California calculates how much money to distribute to school districts. It is based on how many students actually attend school. If you show up, you are counted for funding. California is one of only seven states with an attendance-based formula for funding.

Average Daily Membership (ADM) is used by many states as a basis for allocating funds to districts. Schools receive funding based on average daily enrollment, regardless of whether students show up. Other states base funding on enrollment counts for specific dates or periods.

Absences and equity

California and other states adopted attendance-based funding for sound reasons: Attendance is strongly connected to learning. Attendance-based funding gives schools a powerful incentive to address chronic absenteeism and truancy. Get kids into the classroom or you will lose money! This incentive has had both intended and unintended consequences. On the plus side, schools and districts have invested significantly in programs that get students to school, knowing that those investments can pay for themselves.

The unintended consequence, however, is that this tough-medicine approach is much harder on schools in lower-income communities than on those in wealthier areas. Children in lower-income settings are more likely to have chronic illnesses, or to lack health care. They may have greater responsibilities at home, for example to care for younger siblings. They are more likely to have suffered trauma and to live in dangerous neighborhoods.

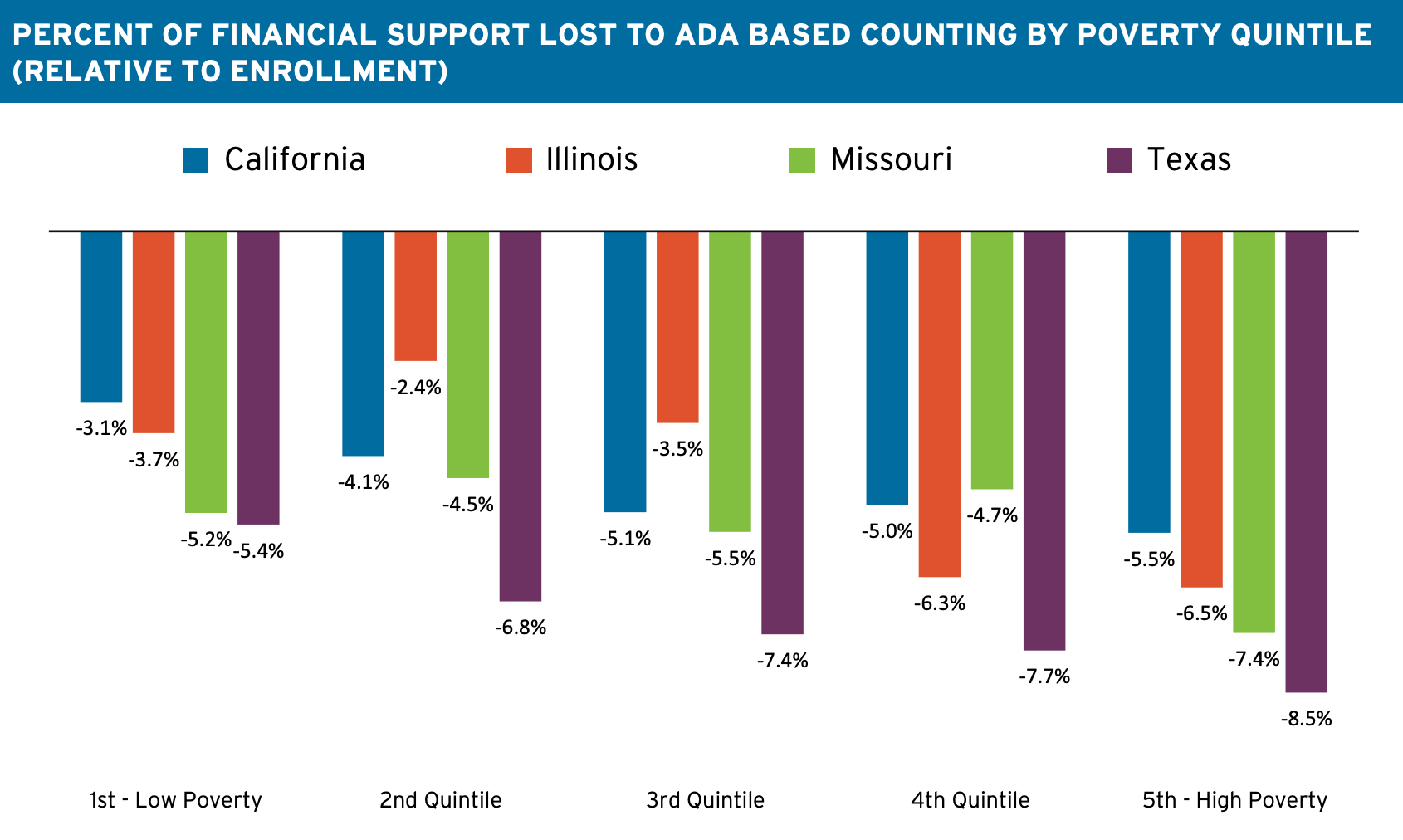

These differences are measurable. Rutgers University professor Bruce Baker demonstrates the disparate impact of poverty on attendance in a paper featuring the chart below. The higher the level of poverty, the greater the loss of funding based on attendance. The left side illustrates the minimal impact on more wealthy districts. The right side shows the large impact on the poorest districts.

The report finds that “By reducing state aid to schools on the basis of student absences, states are disproportionately (and substantially) penalizing schools that serve children from lower-income families — children who are far more likely to suffer childhood obesity, asthma, and other chronic diseases; and far more likely to be absent from school as a result.”

California’s attendance-based system might change

The combination of the pandemic and a general trend toward declining enrollment is spurring discussion about changes.

A little background is important. California’s formula for allocating funding to school districts is known as the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Simplifying heroically, districts receive money based on the students who show up for school. In very rough terms, the value of a day of student attendance (in terms of state funding) is on the order of $65. Governor Newsom’s budget proposal for 2022-23 would tweak this formula slightly to give districts time to adjust when attendance dips or declines. Under the Governor's proposal, district ADA-based funding would be calculated using attendance in the current year, the prior year, or the average of three prior years, whichever is higher.

The governor's proposal is a fairly narrow, technical adjustment. California Senator Anthony Portantino is proposing a much bigger change with his bill SB 830, which would deliver supplemental funding to districts in a quantity sufficient to make up for the difference between what they would receive under an attendance-based system and an enrollment-based system. This enrollment-centered approach is called Average Daily Membership (ADM). Because school enrollment is, by definition, greater than school attendance, it could mean significant additional money for local school districts — up to $3 billion more, according to the senator.

Pros and Cons

In any consequential legislation, some tend to benefit more than others. Lines of support and opposition have not yet formed, but Tony Thurmond, the California Superintendent of Public Instruction, has signaled that he will advocate for enrollment-based funding:

“Districts currently plan their budgets and expend funds based on enrollment but receive funds based on attendance. For example, if a school district enrolls 100 students but their attendance rate is 95%, the school district must still prepare as if 100 students will attend class every day. As such, school districts do not receive funding if a student does not attend school on any given day despite having fixed educational, programmatic, and operational costs.

SB 830 gives districts predictability on how they receive funding and gives them important resources to address what has been one of our most perplexing challenges: dealing with chronic absenteeism in ways we have not yet seen before. It will put students and schools on a better path to further close opportunity and education gaps.”

The burdens of dealing with attendance issues fall on districts unequally because chronic absenteeism tends to be a bigger problem in lower-income school districts than in higher-income ones. Consequently, a shift to an enrollment-based system would tend to benefit lower-income communities more than higher-income ones. According to Pace Connection in a post for the Public Policy Institute of California, “A switch to enrollment-based funding in Los Angeles could mean a 22.5% increase in funding through the state’s funding formula.”

Not everyone agrees that it would be a good idea. In a 2013 study, Todd Ely of the University of Colorado concluded that “states with high incentive student count methods have statistically and practically higher graduation rates.”

Lance Izumi, senior director of the Center for Education at the Pacific Research Institute, questioned the wisdom of dropping attendance incentives in a post for EdSource:

For California’s chronically failing public school system, reforms need to be geared to incentivizing the adoption of proven strategies that will raise the achievement of students and meet their individual needs. Guaranteeing school funding regardless of whether students think schools are worth attending will not improve the quality of public education in California.

The amount of money at stake is significant. Senator Portantino's bill, if passed in its current form, would direct $3 billion in funding to school districts and modify the way that the system supports efforts to boost attendance.

Tags on this post

Attendance Equity Reform PandemicAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Jennifer B February 14, 2022 at 4:57 pm

Carol Kocivar February 14, 2022 at 9:34 am

Jennifer B February 14, 2022 at 5:07 pm