How Should the Success of Schools Be Measured?

The success of schools, per se, cannot be the primary concern of education. Schools, after all, are only a means to an end. The center of the proverbial target is simpler, but even more difficult: prepare EACH child for adulthood.

EACH

The effort to provide opportunity for each student is a costly undertaking, and public education is its biggest component. Spending on universal K-12 education in California adds up to about $65 billion annually when all the sources (state, local and federal) are counted. To put this number in human context, taxpayers in California invest on the order of $121,000 in each student’s thirteen years of K-12 education - roughly equivalent to paying a little over minimum wage for every hour a student spends in class.

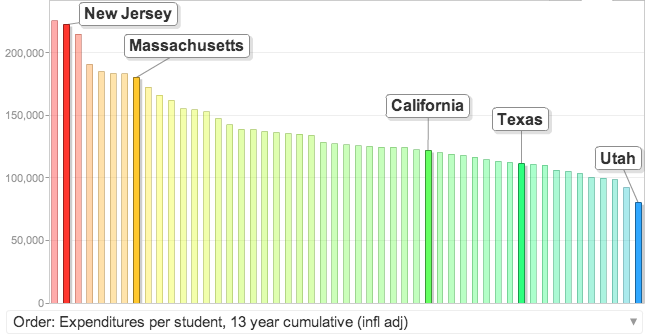

California education spending per student is somewhat lower than middle-of-the pack, and has been so for a long time. (2012 data) Additional charts like this one can be found on EdSource.org (look for States in Motion)

California education spending per student is somewhat lower than middle-of-the pack, and has been so for a long time. (2012 data) Additional charts like this one can be found on EdSource.org (look for States in Motion)This investment is important in lots of ways that have little to do with money. As with any sustained investment, however, success must also be measured in terms of Return on Investment (ROI). Measuring success on these terms requires long-term data about each student’s long-term success, viewed broadly and over a time frame spanning decades, not just school years.

What is the long-term economic payback on that $121,000 investment for each California student? Today, we don’t really know. Evaluating the return requires estimating both value produced and costs avoided. Education produces value by helping each student find his or her place in the world, including work that earns enough to pay taxes. Education avoids costs by helping students grow into self-supporting, resilient and law-abiding adults. Our system is set up to track neither.

The [now-defunct] Academic Performance Index (API) for about a decade stood as the dominant tool for summarizing a school’s performance in California. This score, distilled annually from a changing assortment of annual tests, serve[d] as a shorthand metric of academic achievement at the school and district levels by grade level. Unfortunately, measures like the API can only measure the academic success of those who show up. If every struggling student in a school were to drop out, the score for that school would, perversely, rise.

The state’s system of measurement for education should be built online, in a manner that allows students to show what they know regardless of their nominal grade level. If this seems like whimsy, take a look at the coaching module of Khan Academy for an early example of what the future of measurement may look like, at least in math.

Bringing us up to date

The public has grown accustomed to the idea that products and services should be evaluated, rather frequently, and that evaluation should lead to action. In order to sustain public support for investing in education, California needs to make a set of serious investments to systematically provide everyone involved with better, more personally useful information over a more meaningful arc of time. We rely too much on summary numbers partly because that is all we have at present. California should do better.

For starters, California should invest in modern data systems to track and support investments in human development including education. In the age of Facebook, it is no longer OK for California’s education system to operate with outmoded data systems. California needs a platform that usefully connects parents, students and teachers, including accurate data to inform the work they do together. This is not an investment that each district can or should pursue on its own; it is far too difficult, much too important, and frankly its implications extend beyond education.

A version of this post first appeared in answer to the question "How should we measure our schools?"

Tags on this post

SuccessAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .