Closing a 6,000 Hour Learning Gap

Want to close the achievement gap? Look outside the school day.

Kids spend most of their time outside of the classroom. They are learning and developing constantly—not just between the hours of 8am and 3pm. Families understand this. That’s why those with resources pay for out-of-school classes, tutors, sports, and camps.

In fact, as Robert Putnam describes in his book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, over the last 40 years, upper-income parents have increased the amount they spend on their children’s enrichment activities by 10 times the amount of their lower-income peers. Meanwhile, students from low-income families have increasingly less access to engaging activities, new experiences, caring adults outside their families, and fewer opportunities to build academic, social, and emotional skills.

Upper-income parents have increased the amount they spend on their children’s enrichment activities by 10 times

By the time they reach 6th grade, upper and middle class students spend 6,000 more hours learning than do kids born into poverty. Of those 6,000 hours, over 4,000 are spent in after school and summer programs. This unequal access has immediate consequences for academic achievement and long-term consequences for success later in life.

These differences in how students spend their time outside of school presents one of the biggest challenges—but also one of the biggest opportunities—for California’s education system.

"We can't expect a 20% solution to solve 100% of the problem"

“It turns out that the learning that happens in the 80% of waking hours that are spent out of school ….has as much to do with achievement gaps ... as anything in the school. We can’t expect a 20% solution to solve 100% of the problem; we’ve got to address the inequalities of enrichment and stimulating activities outside of school.”

—Professor Paul Reville, Harvard University Graduate School of Education/Education Redesign Lab

The 80% solution

Local education leaders are mobilizing to support after school and summer learning programs to address the 80% of time spent outside the classroom in order to close the achievement gap. A brief by the Partnership for Children & Youth (PCY) in collaboration with Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE) describes California’s system of publicly funded after school and summer programs. These programs are the result of combining state funds from the After School Education and Safety program (ASES) with the federal 21st Century Community Learning Centers program.

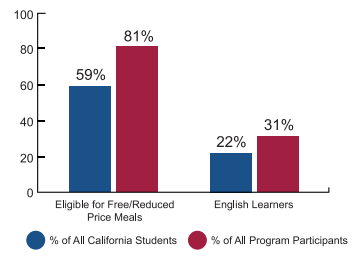

They operate on 4,500 school sites and serve about 860,000 children and youth, most of whom (over 80%) are eligible for free and reduced price meals. The graph below reflects the demographics for the ASES program.

ASES programs are created through partnerships between schools and local community resources to provide literacy, academic enrichment, and safe, constructive alternatives for students in grades K-9. After School and summer programs can offer an additional 690 hours (or 115 days) of learning time—time spent doing hands-on projects in science, technology, and the arts, as well as time spent interacting with positive adult role models.

Evaluations from across the state show that students who participate in quality after school and summer programs increase their reading and math scores, improve their English proficiency, and learn new skills like critical thinking and STEM. Students often experience improved behavioral outcomes, including better school attendance, higher graduation rates, and reduced involvement in juvenile crime.

Funding Shortages—A Little Background

In 2002, California voters approved Proposition 49 to provide after school education and enrichment programs for children in kindergarten through 9th grade. Funding for these after-school programs, however, remained stagnant for a decade. Relief has been recent and slight.

In 2017, the daily funding formula increased a bit, from $7.50 to $8.19 per child. But this was only about half the funding needed to keep pace with the $11 minimum wage. More increases will be needed as the minimum wage rises to $15 by 2023.

While these programs operate successfully throughout the many diverse regions of California, funding is still very thin. And though the state infrastructure for these programs is strong, the demand far exceeds current resources. Thousands of students and families across the state sit on waiting lists.

Two state policy efforts are currently underway seeking more statewide funding for public after school and summer programs:

- A budget request to increase the ASES daily rate from $8.19 to $9.25.

- A bill, AB 1744, that would ensure that after school programs are prioritized to receive tax funding from sales of cannabis (Proposition 64).

Even if successful, these initiatives won’t fully meet the need for after school and summer program funding. Districts concerned about equity and the achievement gap will need to invest their own funding to make sure students have access to high quality programs outside of school hours.

California is well-positioned to narrow the gap

Under the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), districts have greater flexibility and an increased expectation that they address achievement gaps for low-income students, English Language Learners, and foster youth. This means that districts have both the added incentive to help these students, as well as the ability to direct funds toward those strategies proven to make a difference.

School officials throughout California are taking advantage of existing after school and summer programs to do just that.

Examples of Innovation |

|---|

San Bernardino City Unified School District has committed a $2 million annual investment in their after school and summer programs, enabling more students to attend. |

|

San Francisco Unified School District has made clear that their after school and summer programs are part of the core work of their schools. The after school director works with district leadership to ensure that their programs support other school initiatives, like community schools, social-emotional learning, multi-tiered systems of support, and school climate and culture. |

San Leandro Unified School District leads joint trainings on social-emotional learning. |

South Bay Unified School District in San Diego County encourages its schools to hire staff from their after school partners and vice versa. |

These and other districts show that when after school program staff and school day staff work together, are trained together, and have a shared understanding of goals and activities, they are able to provide more opportunities to the students they serve together.

What does an Expanded Learning program look like? It can vary. Each community develops programs that meet the needs of its students. Here is a peek at one program in Compton:

What You Can Do

Is your school struggling to provide after school and summer programs? What are you doing about it? Here are some suggestions:

- Ask your district and local elected officials to support the Save After School Campaign. Sign up for advocacy alerts here.

- Get involved with your district’s Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP) process and advocate for greater investment in after school and summer programs. Here are some tips on how to get involved.

Jessica Gunderson is the Senior Director of Policy and Communications at the Partnership for Children & Youth (PCY). Before joining PCY in 2011, Jessica worked as a senior planner at the Vera Institute of Justice in New York City, where she led research and planning efforts to address chronic absenteeism among teenagers. She also worked for California State Assembly Majority Leader Karen Bass, where she focused on child welfare and social service issues. Jessica received her Master of Public Administration and Non-profit Management degree at the Robert F. Wagner School of Public Service at NYU.

Jessica Gunderson is the Senior Director of Policy and Communications at the Partnership for Children & Youth (PCY). Before joining PCY in 2011, Jessica worked as a senior planner at the Vera Institute of Justice in New York City, where she led research and planning efforts to address chronic absenteeism among teenagers. She also worked for California State Assembly Majority Leader Karen Bass, where she focused on child welfare and social service issues. Jessica received her Master of Public Administration and Non-profit Management degree at the Robert F. Wagner School of Public Service at NYU. Stephanie Pollick is a Communications Manager at the Partnership for Children & Youth (PCY). Prior to joining PCY in 2015, Stephanie worked for the National Council of La Raza (now UnidosUS) in Washington, D.C., where she did marketing and event planning. A California native, Stephanie served as assistant director of a summer camp in Berkeley for children age 5 to 15, where she also trained and supervised young adult counselors. In addition, she worked directly with youth in programs around the Bay Area and within transitional housing communities.

Stephanie Pollick is a Communications Manager at the Partnership for Children & Youth (PCY). Prior to joining PCY in 2015, Stephanie worked for the National Council of La Raza (now UnidosUS) in Washington, D.C., where she did marketing and event planning. A California native, Stephanie served as assistant director of a summer camp in Berkeley for children age 5 to 15, where she also trained and supervised young adult counselors. In addition, she worked directly with youth in programs around the Bay Area and within transitional housing communities.

The Partnership for Children & Youth (PCY) is an advocacy and capacity-building organization championing high-quality learning opportunities for underserved youth in California, with an emphasis on after school, summer learning, and community schools. For over 15 years, PCY has inspired and helped people, organizations, and systems to leverage their existing resources and work together to educate and support children in under-resourced communities.

Tags on this post

After school Equity Summer Expanded LearningAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .