School Facilities in California: Who Pays?

A Very Different Prop 13

In March 2020, Californians will vote on Proposition 13. It's bound to be a little confusing.

Californians know "Prop 13" as the name of an iconic 1978 ballot measure that upended funding for public education. But like numbers on baseball jerseys, proposition numbers in California are reused. Perhaps jersey number 13 should be retired. In 2020 a wholly different ballot measure will bear the number 13 — the California School and College Facilities Bond.

What Will This Prop 13 Do?

This proposition, if approved by voters, will give the state authority to issue up to $15b in bonds to support the construction and modernization of school facilities, including both preK-12 schools and public colleges and universities. To get at the money, school districts will have to match it by passing their own property tax measures.

The law that authorized this proposition and placed it on the ballot, AB48, set some new rules about how the money will be disbursed, and the types of projects that will be prioritized.

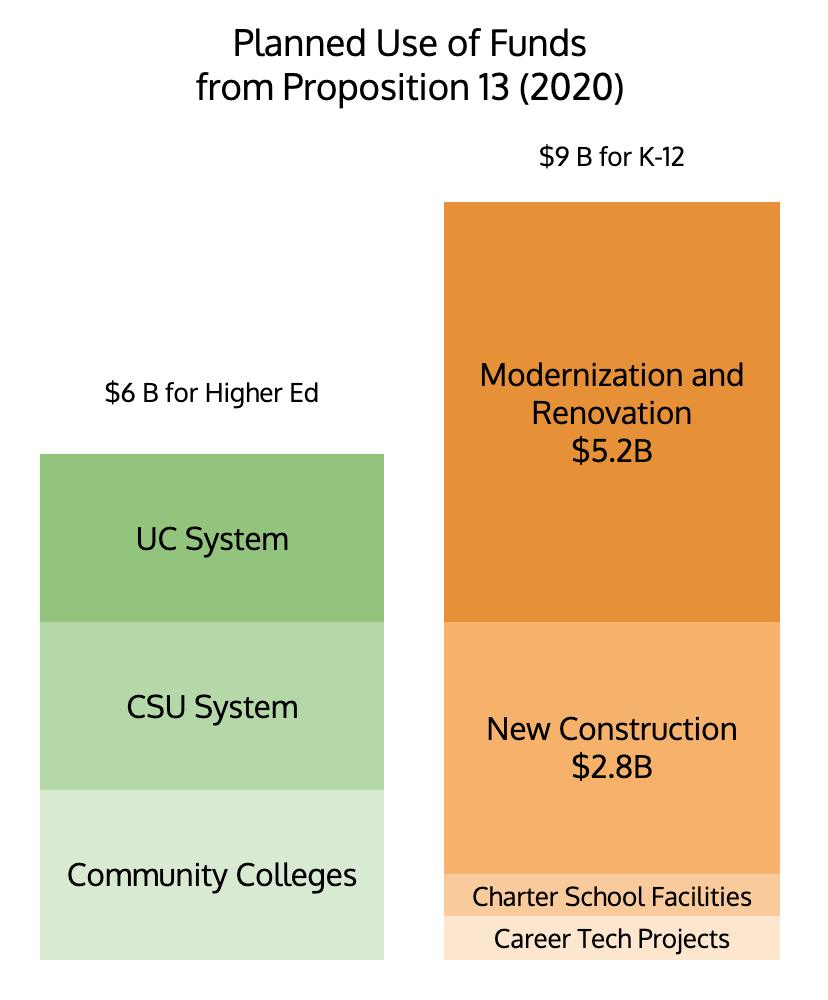

The state's three systems of higher education will each get $2 billion for a subtotal of $6 billion. The preK-12 public education system will receive $9 billion, of which $5.2b will go toward modernization and renovation of existing facilities and $2.8b will go toward new construction. The remaining $1 billion will be split evenly between career tech projects and charter school facilities projects.

If voters pass this measure, the state is granted authority to sell bonds (with the proceeds placed into a fund). The Department of Finance then has the authority to decide how much and how often bonds are sold. The state Department of General Services then oversees disbursement of funds based on the provisions of AB48.

Let's Focus on K-12

But let's back up a little. First, a few big points to understand:

- Most of the burden of school construction and maintenance is borne locally, through local school bonds repaid by local property taxes. (Read on!)

- The state has a history of contributing, too, using state school bonds repaid by state taxes.

- State bonds have supported school construction in more-wealthy districts more than they have in less-wealthy districts.

State and local school bonds often blend support for K-12 facilities with support for college facilities. In the rest of this post, all figures relate only to bonds (or the portion of them) for pre-K-12 projects.

Borrowing it Forward

As in most states, school communities in California rely on a combination of state taxes and local taxes to build and maintain schools. It would be even more accurate to say that California communities rely on future local taxes to pay back bonds sold to finance school construction and maintenance, with some help from future state taxes.

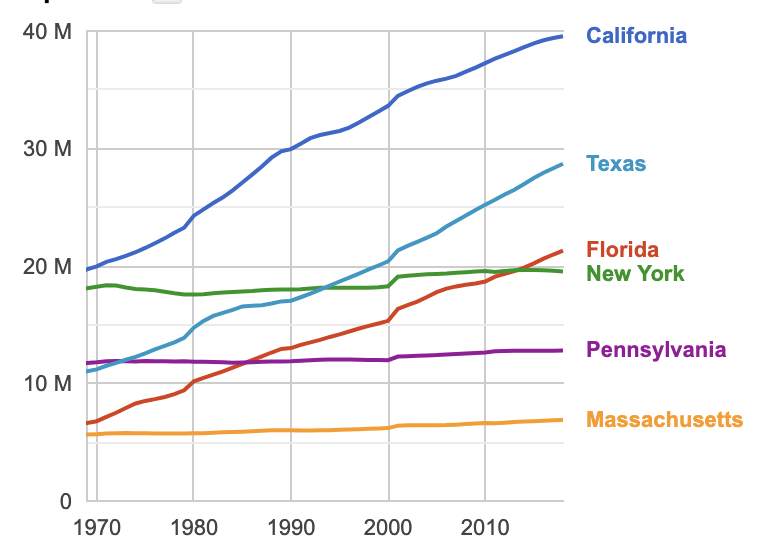

Population in select US States since 1970. (Source: US Census). Where population has grown quickly, like California, so has the need for school construction.

Population in select US States since 1970. (Source: US Census). Where population has grown quickly, like California, so has the need for school construction.Compared to most states, California's population has grown quickly, constantly requiring new classrooms to be built. (Or rolled onto the playground — California's schools make heavy use of prefabricated "portables.") With maintenance, schools can last a long time, but not all construction is of equal quality, and building codes change. Many of California's older schools have problems with lead contamination, for example, which can be expensive to address. Periodically, schools need major renovation or outright replacement. School districts maintain their facilities through a combination of regular operating funds (the money that pays for everything from pencils to teacher salaries) and capital funds (the money raised from bonds).

Like homeowners, many school districts spend less than they should on ongoing maintenance. Instead, they defer — kind of like letting the "oil change" light shine and hoping for the best. When it can't wait anymore, they borrow money. They pay it back over time. With interest, of course.

This State School Bond Proposal Is Ordinary, Yet Innovative

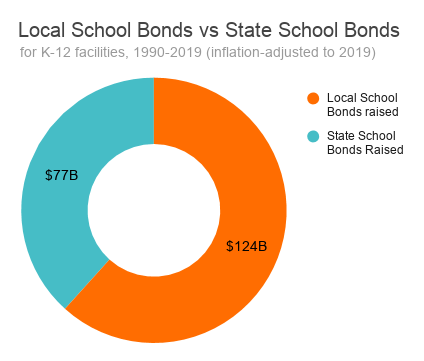

Prop 13 (2020) has strong precedents. This is not the first time California has used state bond measures to commit state funds for school construction and modernization. There have been many such measures in the past; in the three decades up to 2019 eleven made it to the ballot. Ten passed, paying for facilities for both K-12 schools and higher education. Adjusted for inflation, over the last thirty years state bonds have delivered about $77 billion in funding for K-12 facilities.

Local School Bonds Are Even More Important (and Less Fair)

An even bigger portion of the cost of building and modernizing school facilities during this period has been carried by school districts. Adjusted for inflation, in the last three decades school districts in California issued local bonds to borrow about $124 billion for local K-12 school facilities projects. Of course, more-wealthy communities tend to be better able to pay than less-wealthy ones. As discussed in Ed100 Lesson 5.1, where you live makes a big difference in California's education system.

What About Interest?

School facility bonds are loans. The size of a school bond (whether state or local) is usually expressed in terms of its principal — the amount of money that it will raise, hopefully soon. But the total long-term cost of a school bond also includes fees and interest.

For example, Prop 13 (2020), if passed, obligates the state to make payments of a bit less than $1 billion per year for the next 30 years to secure $15 billion in school facilities funds now. The state of California currently has a good credit rating, and rates are low at the moment. Even so, the cost of interest will add up to $12.4 billion according to the California Assembly floor analysis of AB48.

Local school bonds work in much the same way. The school district asks voters for the authority to issue debt (sell bonds) for school facility repairs and/or construction. If the voters say yes at the polls, the process moves forward. A tax based on the assessed value of property is levied according to the terms of the measure approved by the voters.

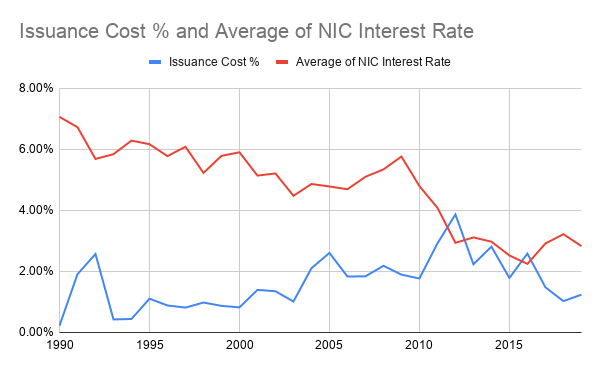

During the three decades examined above, average interest rates on local school bonds (NIC in the chart below) have fallen, which is a very good thing for school districts. Up-front fees (issuance costs) are part of the mix, too.

A school facility bond is a contract between the school district and its underwriters — the businesses, banks or investors that commit ahead of time to buy the bonds. A fairly small number of financial firms specialize in the business of underwriting bonds for school districts in California.

How much do the bankers make on these bonds? It depends. If your school district is growing, has adequate reserves and a good credit rating, it can borrow more cheaply than if it has a history of fiscal mismanagement and declining enrollment. You can find details about your school district's credit rating and its current debts through the DebtWatch service on the site of the California State Treasurer.

Fairness in Facilities

Some of California's schools are new buildings, many of them built to serve the state's expanding suburbs. But an awful lot of school buildings in California are not new. Renewal of these facilities is the emphasis of Proposition 13 (2020).

In poorer school districts, shouldering the cost of school construction and renovation can be really hard, even with state matching funds. Just putting a bond measure on the local ballot costs the district money. Developing and passing the measure requires lawyers, analysts, a public relations campaign and community organizing to make the case to their voters that these funds are needed and worthy of support.

School districts that serve new or higher-wealth communities in California tend to have good facilities that support education and extracurricular programs. They don't have problems with lead-tainted drinking fountains. They have been built or updated for earthquake safety. They have functioning air conditioning systems. Every part of the campus is blanketed with access to Wi-fi.

But there are plenty of challenges even in the state's higher-wealth zip codes. The costs of construction vary massively on a regional basis. Facility improvement projects are by their nature specific: they happen one school at a time, or even one building or classroom at a time.

A New Approach To Matching Funds

Like past state school bond measures, Proposition 13 (2020) is set up as a matching fund. Districts and their voters have an incentive to pass local bonds in order to get state matching dollars. The matching funds are limited — it's a "while supplies last" situation.

Matching funds will go to districts where schools have higher needs

In the past, state matching funds have disproportionately benefited wealthier school districts, according to research undertaken for the Getting Down to Facts II project. Among other reasons, wealthier school districts tend to have their act together. They can get financial documents completed quickly and correctly. In the past, this was a decisive advantage, because funds were reviewed and granted in the order received. Prop 13 (2020) aims to avoid repeating this outcome.

Matching fund requests will no longer be processed in the order received. Instead, the priority order will be determined using a point system defined in a newly minted section of the education code, 17070.56. For example, projects involving lead abatement will receive special priority.

Projects for districts with a low capacity to issue their own bonds or that are in financial hardship will receive higher priority for state matching funds. The proposition also is designed to deliver additional state matching funds based on the proportion of students that qualify as high-need under the definition used by the Local Control Funding Formula.

To apply for these matching funds, school districts will have to submit a five-year plan explaining how the funds will be used, along with "an inventory of existing facilities, sites, and property" and "the school district’s deferred maintenance plan." This is a new level of transparency.

AB48 is a long bill, and there are plenty of details. For example, it is designed to help give small districts more meaningful access to matching funds. It includes provisions that reduce development fees for multifamily housing near transit hubs. It sets rules that encourage construction firms to use collective bargaining.

Could Districts Pay It Forward?

Economists tend to look at the world with an eyebrow permanently raised. School bonds borrow resources from the future and spend them in the present. Wouldn't it be more efficient, they might ask, to save for the future instead of borrowing from it? In this dream, school communities would still pay taxes for school construction and upkeep — but instead of borrowing money and paying back with interest, they would save money, collect interest and pay it forward, somewhat like private schools with endowments.

Nice idea, school board leaders and administrators might reply, but where would the votes come from? We have pressing facilities needs now. It's hard enough to get the necessary votes to address facilities needs even when the need is obvious. Fix the buildings now and then we can talk.

Updated November 2019 with expert feedback from Jeff Vincent (Thank you!)

Tags on this post

Bonds Districts Facilities Local funding Prop 13All Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

christy1carter November 19, 2019 at 6:53 pm