Students out of step for middle school

Difficult steps ahead for struggling readers

Even in normal times, stepping up to middle school is hard for a lot of students.

The pandemic threw this transition into crisis mode. Nearly 20 percent of low income students were chronically absent. Students have lost about two years of classroom instruction. It's not unusual for a student who struggled with reading in elementary school to be entering middle school years behind in literacy skills.

The implications for middle schools are huge. It’s one thing to help students catch up in the content learning of math, science, history and language arts. This year middle schools have the unusual job of teaching a lot of students to read.

In normal times, California assesses students annually using the CAASPP tests, and scores are pretty stable from one year to the next. In the 2019-20 school year, the state skipped administration of the test because of the pandemic. When testing resumed in 2020-21, nearly 56 per cent of 6th grade students who took the test were not proficient readers. These scores only hint at the extent of loss, because the test was optional — many low income students and students of color did not take it. The scores probably understate the challenge.

Students rising to middle school are seriously out of step with expectations built into the standards.

Three challenges for middle schools

1) Middle school teachers are not normally trained to teach basic literacy.

Education standards are aligned from one grade level to the next, so that educators can have a reasonable expectation that students have learned grade specific literacy skills. Secondary teacher training and professional development reflect those expectations.

Middle school: Reading to Learn — not learning to read

Teachers at the secondary level are trained to teach content, not literacy development.

2) Diverse literacy needs make instruction more difficult.

Middle schools are designed to follow secondary grade specific standards. These standards require students to interact with content to learn as opposed to strengthening their reading skills.

Let us look at a seventh grade standard to provide clarity.

|

Grade 7 reading comprehension |

|

|---|---|

|

“Assess the adequacy, accuracy, and appropriateness of the author’s evidence to support claims and assertions, noting instances of bias and stereotyping.” |

|

This standard assumes students already possess decoding, reading fluency, and comprehension skills. Any student in a seventh grade English class, reading at a third grade level, and needing additional support to decode multisyllabic words, will not receive the necessary literacy instruction. With a business-as-usual approach, middle school teachers do not have time for in-depth literacy instruction due to a focus on content, standards, and pacing guidelines. (Pacing guidelines are the recommended time a teacher should provide for a topic.)

Reading levels for a seventh grade class can range from the second grade to beyond the eighth grade level. The ability to teach a seventh grade standard, Reading Comprehension, 2.6, is made more complicated by the need for the teacher to differentiate the lesson based on massive differences in reading abilities.

Normal middle school bell schedules shorten literacy learning time

A third challenge to middle school literacy development involves the bell schedule. Bell schedules promote urgency. Teachers have limited time for instruction in a given class and pacing guidelines can force them to rush. (Textbook companies and organizations create guides for their books and Common Core subjects to ensure all topics are covered within the available time to help teachers meet standards.)

Rushing through content does not put the needs of students first. It prioritizes the needs of adults. There are consequences. Students needing more intensive literacy support are often left to struggle, an unproductive daily exercise that constantly reminds them of their limited proficiency. A constant reminder of one’s limited proficiency in reading can lead to an unhealthy internal dialogue. What was once a need to learn becomes doubt and part of a student’s belief about who they are as learners.

Strategies for Change

Without significant changes, a generation of children will fall far short of meeting California's grade level content content standards.

Crisis really does create opportunity. School districts have very broad power to change the way they use time and resources. There are many specific steps school districts can take to meet the literacy needs of middle school students. The pandemic has highlighted gaps in the system. If normal approaches aren’t working, it is within your district’s power to change them.

The strategies below can help middle schools be more responsive to student needs.

|

More time for instruction |

|

|---|---|

|

The problem: A typical middle school class is not long enough to teach both content standards in language arts, math, science, social studies and differentiate instruction for literacy skills. For example, in one district, the teacher workday began at 8:05 am and ended at 3:45 pm. Actual class time began at 9:05 am and ended at 3:30 pm. Students did not have access to teachers in the morning between 8:05 and 9:05 am. That left only 15 minutes after school to meet differentiated needs — not enough to address the needs of students. |

The solution: Bell schedules can be changed. Strategic use of the bell schedule is crucial for providing student interventions during contractual hours without taxing the site budget or asking teachers to volunteer their valuable time. For example, in order to provide additional academic support for students who need it, one school changed its start and end times to 8:25 am to 2:50 pm with a minimum day on Fridays (8:25 am to 1:15 pm). This provided students with 55 minutes of additional access to teachers Monday through Friday, adding 3 hours and 40 minutes weekly for potential interventions. Friday minimum days allow 2 hours and 30 minutes weekly for professional development, examining student work, and adjusting instruction based on analysis. |

|

Comprehensive literacy screening |

|

|---|---|

|

The problem: Middle schools do not know the literacy needs of each student. Unfortunately, many elementary schools do not provide data that would help the middle school know why a student is struggling. Standardized tests reveal a student is behind but they don’t provide a clue about the underlying problem. |

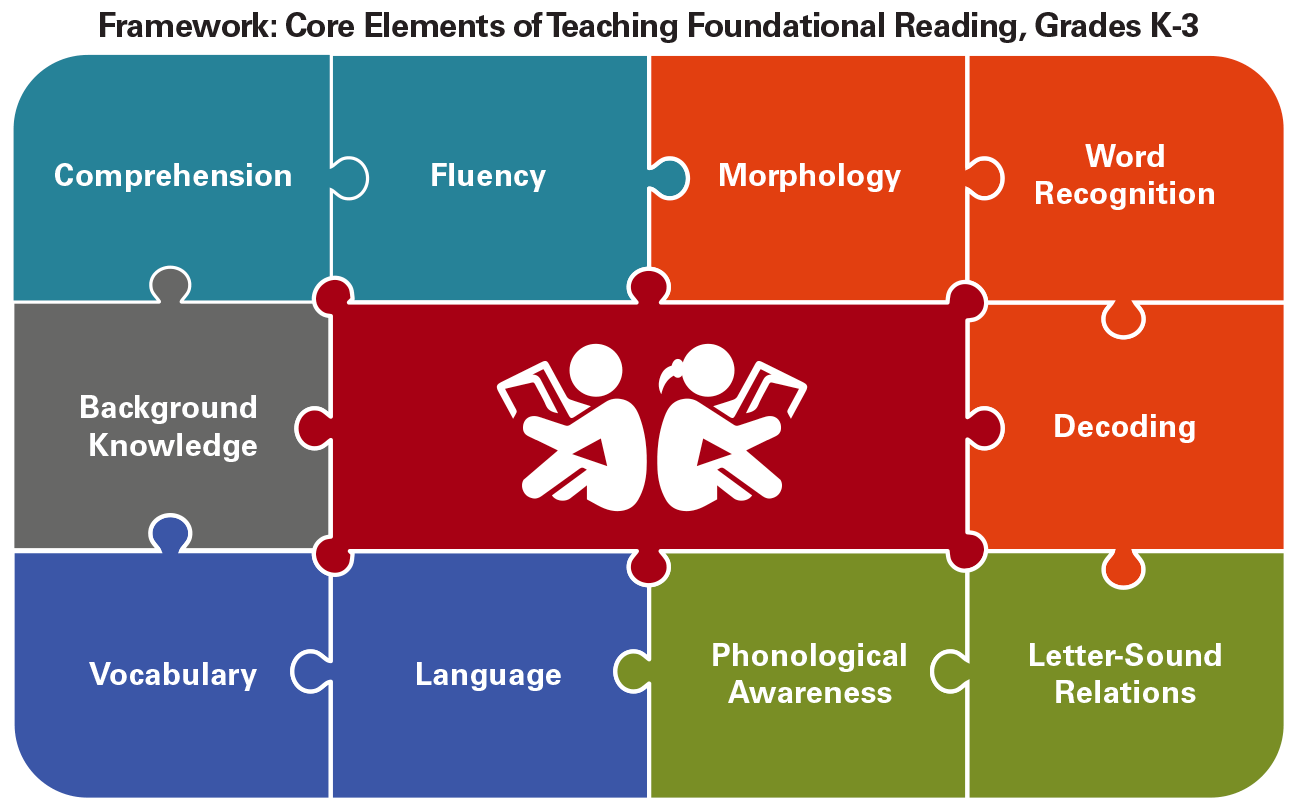

The solution: Every student — 6th through 8th grade — should have the benefit of a literacy screening. Teachers must know what kind of support each student needs, and the assessment should be repeated throughout the school year. Schools need to identify literacy strengths and weaknesses in four areas: decoding, fluency, comprehension, and usage. If you don’t know the specific problem, you can’t effectively fix it. |

|

Secondary teacher literacy instruction |

|

|---|---|

|

The problem: Students arrive in middle school with a need for continued foundational literacy skill development that teachers are not trained to teach. |

The solution: Middle school teachers must participate in professional development and build their capacity to teach literacy. This will allow teachers to incorporate literacy strategies to support student needs identified in a literacy screening. These strategies must be evidence-based with research showing they have positive effects on student achievement. The Educator’s Practice Guide contains four evidence-based practices that middle school teachers should be able to implement. |

This image from The Place summarizes extensive recommendations from the Institute of Educational Science (IES)

|

Tracking students |

|

|---|---|

|

The problem: Students who struggle with literacy do not all have difficulty with the same skill. A child who can decode may not have the vocabulary to understand a lesson. This is particularly true for English language learners. A child may be unable to combine sounds to create words. A child may be unable to meet writing goals. Many students can read words but lack comprehension of ideas. |

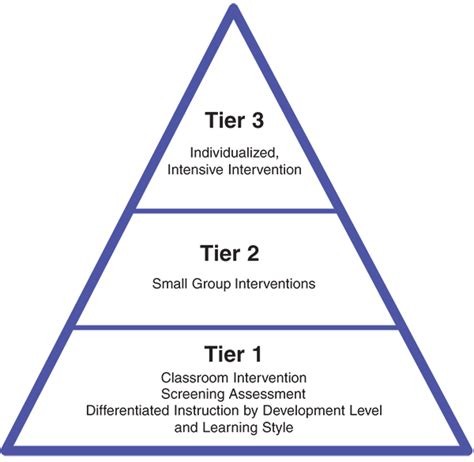

The solution: Redesign the master schedule to support flexible grouping based on ongoing assessment and student need. These learning groups are based on student literacy needs rather than reading level. For example, students who are struggling with morphology would be put in the same group. The initial screening assessment provides the data teachers need to create these groups. This approach leverages time for teachers. After students learn a skill they can move to a different group. |

|

High quality literacy instruction at elementary level |

|

|---|---|

|

The problem: Too many students are arriving at middle school with significant gaps in their literacy development. Students are entering middle school not knowing digraphs (two letters representing a single sound, e.g. ch, th), how to spell sight words, limited reading fluency, comprehension… |

The solution: A heavy concentration of district resources to deliver high quality evidence-based literacy instruction in Pre-K through 2nd grades. Any student requiring additional support must have access to resources to meet their identified needs. High quality instruction is not limited to the classroom setting. It must include targeted tier 2 and tier 3 interventions when necessary, and continued support at home. |

|

Student-led conferences |

|

|---|---|

|

The problem: Students do not take responsibility in their literacy development. Teachers communicate the areas of growth and concern for students. Students take a passive role in their own educational development. |

The solution: Students familiarize themselves with their literacy screening. They develop goals based on their literacy screening and track their growth in preparation for the Student-led Conference. The student shares artifacts indicating their progress towards completion of the generated goal. This assists with building a positive internal dialogue for a student and creates ownership over their literacy development. |

Michael Essien is president of United Administrators of San Francisco and principal of Martin Luther King middle school. Carol wrote about his work to develop community schools in San Francisco. Essien can be reached via Twitter @MichaelCEssien

Michael Essien is president of United Administrators of San Francisco and principal of Martin Luther King middle school. Carol wrote about his work to develop community schools in San Francisco. Essien can be reached via Twitter @MichaelCEssien

Tags on this post

All Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .