How are teachers trained?

Great teachers really, really matter. It’s time to improve how we prepare them.

Nothing at a school matters more to a student’s future than great teachers. Effective teachers can make challenging subject matter come alive. They can ignite passion for learning in ways that improve attendance, increase graduation rates and make a difference in ways that last. As Edutopia summarizes, an effective, well trained teacher is likely to send more students to college and can boost a class’s lifetime income astronomically.

Explained by

Explained byLeslie Reckler

and Carol Kocivar

The relationship between each student and each teacher is personal, but these connections exist in an organizational context. To be successful for kids, the education system has to recruit, train, and cultivate effective teachers at an enormous scale. It also has to provide suitable safeguards to help school districts avoid mistakes in hiring.

Not everyone who wants to teach is ready to be good at it.

Not every person who wants to teach is ready to be good at the job. An effective state education system has to support effective judgment about readiness. This is not a new insight — it has been a point of policy tension for decades.

This post explains the processes that have been developed to help school districts hire good teacher candidates — and avoid hiring people who are unready, or who would be better in another line of work. It’s a timely matter because change is in the air. Many believe that the way teachers are trained in California isn’t working well enough. An important requirement of the teacher prep process, the Teaching Performance Assessment (TPA), is changing. Some think the changes are on the right track and counsel patience. Others, notably the California Teachers Association, are calling for the requirement to be dumped entirely.

This is consequential stuff. What’s going on here?

How are teachers trained and certified?

Let’s back up. As Ed100 Lesson 3.2 explains, in order to become a teacher in California’s public schools, you need a certificate. There are many pathways to qualify for one before beginning work in the classroom. The traditional pathway requires a bachelor’s degree, completion of a credentialing program (usually at a college), passage of some tests, and experience as a student teacher. It also requires completion and review of a fairly extensive set of materials (in written and video form) collectively known as the Teaching Performance Assessment (TPA).

Here’s the thing: in many districts, the supply of traditionally-prepared teacher candidates has not kept pace with local needs. The market for teaching jobs (demand) is not perfectly matched with the number of prepared candidates ready and available to fill them (supply). When districts have money in their budget to hire people, they tend to pounce, hiring interns or awarding emergency credentials to secure whatever talent they can find, ready or not.

Even if they are initially hired on an emergency basis, teachers must eventually earn a “clear” teaching credential to certify that they have met all requirements, including the Teaching Performance Assessment.

How effective is teacher training in California?

In 2024, the state of California revised its standards for the teaching profession, prompting new questions about who becomes a teacher, with what requirements, and through what processes.

Many teachers resent the process of becoming a teacher. As this EdSource article and its robust comments make clear, it can be bureaucratic and costly, and some feel the requirements aren’t all well aligned with the actual job. The teacher training system in California has had many vocal critics. For example, in 2018 Marc Tucker, founder of The National Center on Education and the Economy (NCEE) bluntly singled out teachers colleges as “the weakest link in our public education system.”

In 2016 the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) substantially revised the framework it uses to occasionally accredit institutions with teacher programs. Have these revisions made a difference?

Maybe. According to a 2023 report by the Learning Policy Institute (LPI), the revised framework offers reason for hope in the long run. A study of new teachers who completed a newly accredited program under the revised framework found that 90% rated their program as “effective or very effective” and felt “at least adequately prepared in all areas represented by the state’s teaching performance expectations.” There was some variation. Teacher preparation programs at University of California (UC) colleges earned the highest ratings.

Unfortunately, change through attrition and replacement is a recipe for excruciatingly slow improvement in a state with about 300,000 teachers and many prep programs.

The slow implementation may have contributed to a grim report by the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) in 2023. Of 41 teacher preparation programs it examined in California only two earned an “A” for preparation in researched-based “science of reading” instruction. Twenty-four programs earned an “F.”

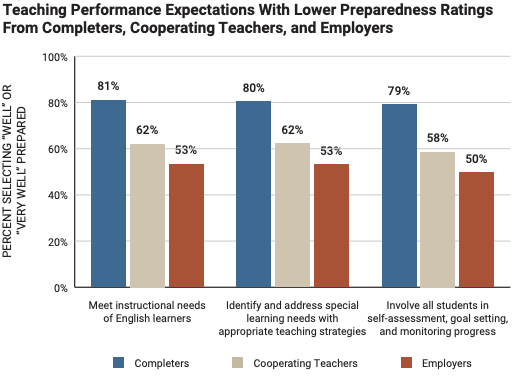

In 2018-2021, the CTC assessed the impact of its revised framework in a massive survey of newly-prepared teachers, their mentors and their employers. As new teachers exit their prep programs, they go through an evaluative exit process. Are they ready to teach English Learners? Are they prepared to identify and appropriately address special learning needs? Can they involve students in assessing their own learning progress? The survey findings suggest mixed reviews with a lot of doubt, especially from employers. New teachers tend to think they are well-prepared; many employers don’t share this view.

This analysis includes three years of data (2018–19 to 2020–21) and a restricted sample of Teacher Preparation Programs (TPPs) in which at least 5 completers have responded and at least 5 cooperating teachers or 5 employers have responded (N = 78 TPPs). Completers are asked, “How well did your teacher preparation program prepare you to do each of the following as a teacher?” Cooperating teachers are asked, “How well-prepared was your student teacher to do each of the following?” Employers are asked, “Compared to other beginning teachers with whom you have worked, how well-prepared are program completers to do each of the following as a beginning teacher?”

Source: Learning Policy Institute analysis of Commission on Teacher Credentialing Program Completer Survey data (2023).

In the face of these mixed reviews, schools of education are evolving. The state is in the process of rolling out a new, updated Teacher Performance Assessment that incorporates requirements to improve the teaching of literacy and reading.

Proposal to eliminate Teacher Performance Assessment (TPA)

This gradual improvement process is on the wrong track, according to criticism from the California Teachers Association (CTA), California’s largest teachers union:

“The TPA is an onerous portfolio assessment that detracts from teacher candidates’ ability to focus on applying the concepts and skills of teachers during supervised clinical practice,” according to the organization’s brief titled Take Action to End the TPAs. “While well intentioned, the demands currently placed upon teaching candidates in preparing for the TPA have the perverse impact of actually reducing the overall quality of teacher preparation by undermining the capacity of teacher candidates to focus on their clinical practice.”

With CTA sponsorship, 2024 Senate Bill 1263 (Newman) proposes to repeal teaching performance assessments altogether. (See bill analysis.)

The CTA proposal to simply eliminate teacher performance assessments has been met with strong opposition. The state has spent millions of dollars to update an assessment that would be abandoned, with nothing to replace it.

Who supports Teacher Performance Assessments?

Teacher Performance Assessments measure a teacher candidate's knowledge and readiness relative to California's Teaching Performance Expectations. Candidates must also demonstrate their ability to instruct students using content standards.

Leaders of the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) have expressed serious concerns about the bill to eliminate the TPA. In a joint post for EdSource, two of the commission’s leaders summarized their alarm:

“The TPA is California’s only remaining required measure of whether a prospective teacher is ready to teach prior to earning a credential. All other exam requirements for a teaching credential have been modified by the Legislature to allow multiple ways for future teachers to demonstrate basic skills and subject matter competence. These legislative actions have been supported in large part by the requirement that student teachers complete a TPA to earn a credential.

Elimination of the TPA would leave California with no consistent standard for ensuring that all teachers are ready to teach before entering our classrooms. We would join only a handful of states that have no capstone assessment for entry into teaching. Passage of SB1263 would also result in the state losing a key indicator of how well educator preparation programs are preparing a diverse and effective teaching force.”

Education Trust West, a nonprofit advocacy organization, suggests a different approach:

“... rather than eliminating all performance assessments, the state can and should streamline and improve the administration and scoring of TPAs to ensure they are an additive, constructive experience for candidates, and that they do not have a disparate impact for candidates of color. Doing so is critical.”

Do teacher performance assessments work?

Perhaps lost in this kerfuffle is a fundamental question: Do we know whether teacher performance assessments actually work? That is, is the public better off with them than without them?

The answer is yes. In a 2024 report, How Preparation Predicts Teaching Performance Assessment Results in California, Susan Kemper Patrick of LPI lays out the research. “Multiple studies have found that TPA scores predict effectiveness once candidates enter the classroom as licensed teachers.” Among her conclusions from the data:

- TPA passing rates correlate with how well a teacher education program prepares students to teach literacy and math.

- Candidates with more opportunities to learn how to teach literacy and math were more likely to be successful on a TPA.

Most prospective teachers who begin a Teacher Performance Assessment complete it successfully, many on the first attempt.

Unequal Access

Among many other insights, the LPI report also reveals patterns that teacher candidates have unequal access to highly rated preparation and clinical experiences:

“Only 46% of Black and 50% of Native American completers reported participating in student teaching or residencies, compared to at least two thirds of all other racial/ethnic groups.”

What can we learn from other states and countries?

According to the National Center for Teacher Quality (NCTQ), which tracks state policies relating to teacher evaluation and performance, California is not the only US state where policies related to evaluation are being reconsidered and challenged.

Beyond the US, the National Center on Education and the Economy (NCEE) investigates the world’s best education systems and offers actionable advice to help systems everywhere achieve greater results.

The NCEE 2021 Blueprint for a High Performing Education System, based on extensive data analyzed from empirical investigation and worldwide PISA test scores, bears reading. It contains insights from about 30 years of studying and benchmarking many of the world’s leading systems. States and districts can use these insights to redesign their own system for high performance. (Check here for the latest version, which as of this writing is expected soon.)

Among their recommendations, NCEE found that high-performing systems have thoughtful policies in place to recruit, train and sustain a world-class teaching force.

|

Summary of NCEE Blueprint: |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Comparison basis |

High-Performing Systems |

USA/California |

|

Applicant qualifications |

Competitive. |

Not competitive Not highly selective No aptitude screening |

|

Teacher prep content |

Subject matter preparation plus How to teach the curriculum |

Scant instruction on how to teach particular curriculums. Curriculum instruction left to school districts. |

|

Mentoring |

Career path reserved for those with aptitude. Extensive time to collaborate, model, and provide feedback. |

California provides mentoring standards. Limited time to collaborate, model, and provide feedback. |

|

Research |

Training in self-evaluative research and systemwide improvements. |

No mandated training. It’s left to individual school districts. |

|

Care of the profession |

Opportunities to advance. Societal value. Prestige. |

Eroded social standing. Highly politicized profession. Compensation is lower than other professional careers. |

|

Competence and accountability |

Teachers must demonstrate mastery in various ways. Examples include: Peer review of videotaped lesson delivery. Tests to screen for subject competence. Demonstration lesson given to a live panel of experts. |

Measures of teacher competence are being actively eliminated. Teacher candidates no longer have to take the California Basic Skills Test, or CBEST, or the California Subject Matter Exams for Teachers. The California Teachers Association is pushing to eliminate teacher performance assessments altogether. |

Taking the big view

It is unquestionably true that California’s schools need a steady supply of well-prepared, motivated teacher candidates. It is also unquestionably true that this is not the current state of affairs in California. Many districts chronically find it necessary or expedient to hire under-prepared teacher candidates. Those new hires may struggle to do a difficult job that they aren’t prepared for.

Candidates who successfully complete TPA are better-prepared to teach than those who do not. Friction over TPA is partly about the design of the assessment, which many don't know has changed. But it is also a symptom of far larger issues about the attractiveness of the teaching profession.

Policies always have both intended and unintended consequences. The revised TPA has been shown to be effective. In the spirit of “measure twice, cut once” the proposal to summarily scrap the TPA without a ready plan seems rash.

Carol Kocivar contributed to this post.

Tags on this post

All Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .