Why Accreditation Matters for California Schools

What Is Accreditation?

A diploma represents evidence of learning. In order to confirm the value of that learning, most colleges and high schools submit themselves every few years to a process known as accreditation, in which an outside independent team or agency works with a school's leaders to help it examine and evaluate its work.

Accreditation serves two purposes: first, it aims to inspire trust that the school delivers on its basic job — providing high quality education to students at a credit-worthy level of rigor. (Credit is the root word of accreditation.) Second, it demonstrates that the school is serious about self-improvement.

What is WASC and How is it Governed?

The work of school accreditation in the United States is carved up regionally. In California, the organization to know about is known colloquially as WASC. (Formally, it is the Accrediting Commission for Schools Western Association of Schools and Colleges.) A nonprofit membership association, WASC accredits private schools, public schools including charter schools, colleges including community, junior and four year colleges, universities, summer programs, online schools, home schools and more.

WASC is overseen by a commission of 32 representatives from the educational organizations that it serves, including the California State PTA. The commission meets three times a year. Its bylaws are public, as are most of its meetings.

Is Accreditation Common in Other States, or is this a California Thing?

There are no specific federal laws or regulations governing the accreditation of primary and secondary schools, and the U.S. Department of Education has no oversight role. Accreditation authorities are regional, and differ across the United States and worldwide.

As discussed in Ed100 lesson 7.1, in California the buck stops at the state. California law does not require accreditation, but a web of compelling incentives make accreditation important to high schools and post-secondary schools.

|

Some of the Reasons High Schools Seek Accreditation: |

|---|

|

The United States military, the University of California and California State University systems require diplomas from accredited high schools, as do various state-based scholarship programs. |

|

The University of California requires all schools that want A-G approval of courses to be accredited, or be a candidate for accreditation in order for their transcripts to be accepted as evidence of college readiness. |

|

Foreign students must enroll in an accredited institution in order to be eligible for an I-20 U.S. Visa. |

|

California charter schools must be WASC-accredited to apply for charter school building funds. |

So, the incentives to accredit are significant. Middle schools can be accredited as well, and some decide to take that route — especially charter schools that may seek school building funds, or schools that support a 7-12 grade span.

Who is Involved in the Accreditation Process?

Accreditation through WASC is typically a six-year cycle involving self-study, a visit, and then yearly action plans to address and improve areas of opportunity. The most important part of the accreditation process is the school’s look within. WASC asks schools to focus on just a few questions when writing their self-study reports:

- How well are students learning and achieving?

- How do you know that all students are learning and achieving?

- Are you doing everything possible to support students in their learning?

WASC team visits help schools to organize this work with a Self-Study Template. Schools normally appoint a coordinator and assemble diverse teams to dive deep into these areas.

Accreditation team members are volunteers

After completion, the self-study document is sent to WASC, which prepares a volunteer team to validate the self-study report with a site visit. Has the school adequately, accurately and truthfully reflected itself? Do the findings on the ground match the written report?

The visiting team is comprised of educators of different levels and positions, described in the organization's policy manual (See page 41). The teams perform these services on a voluntary basis. Although not paid for their time, their expenses are covered by the visited school.

The visiting committee provides insight to the school through dialogue with focus groups and time spent in classes. Then they prepare a written report and present their findings.

What is the Role of Students in School Accreditation?

At the secondary school level, students should play at least some role in the accreditation process. Thoughtful schools will assemble diverse and well-rounded teams to complete the self-study and be on hand for visits. At the very least, students will be interviewed on visitation days.

What Does an Accreditation Report Look Like?

There is no required format for a WASC accreditation report, but they generally exceed 200 pages. The report must adhere to the WASC criteria (see the Self-Study section), and may include charts, graphs and other visuals outlining progress and opportunities.

Are Accreditation Reports Public?

Schools and districts are not required to release accreditation reports to the general public.

Some schools post WASC-related documents to their websites, either in full (such as Piedmont High School) or in summary form (such as Richmond High School.) To find examples, try WASC’s directory. If the school is listed, and is a public school, the documents can be requested from your school’s principal or school district’s public information officer. Because WASC is not a governmental agency, it is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act.

Is Accreditation Expensive? Who Gets the Money?

Accreditation costs money, but more importantly it takes time.

High schools pay an annual fee for WASC membership (about $1,000) and there are specific fees associated with site visits and other services (see fee schedule).

But most of the costs of accreditation are "time" costs rather than direct expenditures. Each school must prepare an extensive self-study report, assembling a diverse school team to collaborate, research and write. Some schools assign an experienced faculty member to lead the process, reducing his or her teaching load for the year to make it work. The true cost of the investment of time and talent in the reflection process can easily run to hundreds of thousands of dollars. It's important to make sure that the value of the process is in line with its cost.

How Often do Schools Fail Accreditation? What Happens Then?

Schools rarely fail accreditation, which is fundamentally a self-study process with the support of volunteer visiting committees.

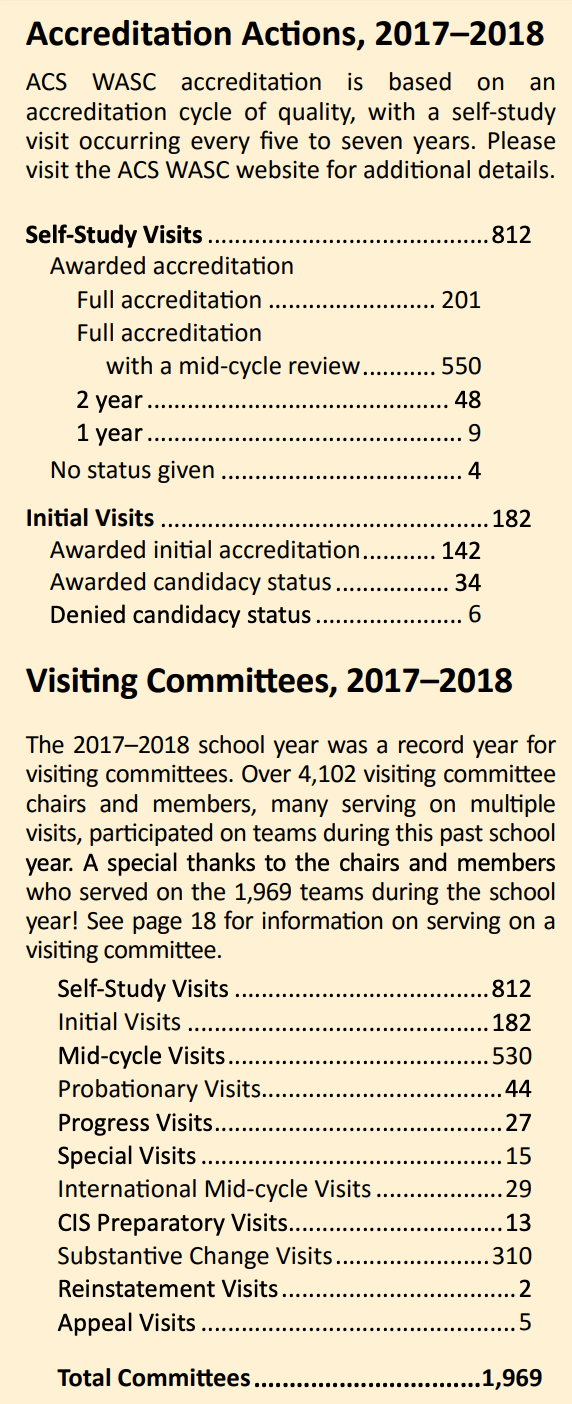

According to WASC’s 2017-2018 Annual Report, 812 K-12 schools and colleges had a self-study visit in that year. About 99% of them were accredited. Almost 25% of committee visits resulted in a full accreditation. About two-thirds were fully accredited with the recommendation of a mid-cycle review - a check-in to see how schools were progressing to plan. About 5% were awarded a probationary visit scheduled for one or two years in the future.

If a school fails to win accreditation, the usual course of action is for the accreditation team to help the school clarify priorities and schedule a followup review in one or two years. If a school is given Probationary Accreditation, it must submit yearly reports and be visited for a number of years until full accreditation is achieved.

How to Get Involved:

First, find out if your school has been accredited, and when. In most schools, accreditation operates on a six-year cycle, so there’s a chance you’ll have the opportunity to participate in your high school’s self-study or mid-year visit. At the very least, ask your principal for a copy of WASC documents to understand what the school and visiting committee feels it does well and where it needs to improve. Ideally, you should see WASC goals and objectives woven into the School Plan for Student Achievement produced by the schoolsite council.

If the opportunity to serve on a WASC team presents itself, try to participate. It's a great way to be a part of a positive change process, and you will learn about what your school community values. If you enjoy the experience at your local school, talk to your school administration about serving on a WASC visiting committee. There are spots available for parents!

Leslie Reckler is President of the Bayside Council of PTAs, the umbrella organization that serves the 30+ PTAs in the West Contra Costa and John Swett Unified School Districts. She's the mother of two and a passionate advocate for public education. She contributes frequently to Ed100.

Leslie Reckler is President of the Bayside Council of PTAs, the umbrella organization that serves the 30+ PTAs in the West Contra Costa and John Swett Unified School Districts. She's the mother of two and a passionate advocate for public education. She contributes frequently to Ed100.Tags on this post

A-G requirements College Quality Rigor AccreditationAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

barry groves April 12, 2020 at 7:26 am

Leslie1 May 30, 2020 at 1:02 pm