The Bilingual Education Advantage

One Big World

About two out of five students in California speak a language other than English at home, and one out of five students is an "English Learner," actively engaged in acquiring fluency. These students have some big advantages in a world that is increasingly connected and multicultural.

At least, they should have some big advantages. Unfortunately, until recently California hobbled students from developing skills in multiple languages. The state has some catching up to do.

The Advantages of Bilingualism

Let's start with the advantages. People with skills in multiple languages have the potential to understand the world at a level that single-language speakers cannot. They can easily enjoy and appreciate music and movies from multiple cultures. They can find jobs in international businesses. They can laugh at puns and jokes that make no sense to mere monoglots (speakers of only one language). They have better cultural empathy. They might even be less apt to get Alzheimer's Disease in old age.

In many countries it is normal to learn many languages.

Multilingualism is common around the world. In the European Union, the average number of languages spoken is two or even three in many countries. In India, South Africa, and many other countries it is normal to learn many languages.

The Challenges of Bilingualism

Learning a language takes some time and effort, even for young children. When children learn more than one language at a time, for a time their test scores in English tend to be slightly lower than they would be if "immersed" in an English-only school environment. However, the delay is temporary, according to powerful research by Ilana M. Umansky and others coordinated for the Getting Down to Facts II project:

"EL students in English immersion programs generally have higher English proficiency and standardized academic test scores by second grade than their peers in two-language programs (bilingual and dual immersion programs). By late elementary or middle school, however, these differences are generally eliminated or reversed. By these later grades, ELs who spend their elementary school years in two-language programs have test scores, English proficiency levels, and reclassification rates that are, on average, as high as or higher than similar students who were in English immersion classrooms."

Most research about bilingualism in California focuses on students who are learning English at school while immersed in a non-English language at home. However, some families are interested in helping their children become bilingual independently of family heritage.

"Immersive" isn't well-defined.

There are many ways to design schools that prioritize language acquisition and fluency, and the terminology that schools use to describe their approaches can vary. For example, schools that prioritize two languages are sometimes known as "dual immersion" schools, especially if they mix students with home experience in two languages. But there is no enforced meaning to the term — if you are considering a school because of its "immersive" language program, it's a good idea to ask for details. How, when and why do teachers and students use each language?

Some bilingual preschools and programs are privately run, with tuition that can run to tens of thousands of dollars per year, but bilingual programs exist in some public schools, too. For example, San Francisco Unified School District has made significant efforts to provide families with a variety of language education options in early grades, including schools with programs in Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Italian, Japanese, Italian, Korean, and Tagalog.

The excitement of schools with a mission to teach language is well captured in the movie Speaking in Tongues.

A Bit of History

California has a complicated history when it comes to multilingual education. In the 1980s and '90s, as immigration from Mexico increased the number of Spanish-speaking students in this state and others, some California schools began developing programs to help students learn in both English and Spanish, but also in many other languages from Armenian to Zulu.

Policy about language education became swept up in political movements related to immigration. In 1984 Californians passed Proposition 187, which attempted to make citizenship or legal residence a condition for enrollment in public school. Promptly challenged in court, the key provisions were blocked and the measure was ultimately repealed in 2014.

In 1997 then-Governor Pete Wilson ran for re-election on a platform to reserve public services exclusively for citizens and legal residents. A pillar of the plan was Proposition 227, the "English in Public Schools" initiative, which restricted bilingual and multilingual programs and clarified that the goal was to quickly make students learn English. The measure passed.

This restriction on bilingual education was the law in California for almost two decades. California voters threw it out in 2016 by overwhelmingly passing Proposition 58, the "Non-English Languages Allowed in Public Education" act.

Bilingual education is legal now, but that doesn't mean it's easy to provide.

Building New Bilingual Capacity

During the years when Proposition 227 was in effect, it was possible for schools to offer bilingual education, but it required a waiver from the State Board of Education. With the passage of Proposition 58, many school districts were immediately interested in offering bilingual education, but most lacked the capacity to provide it.

For a start, providing bilingual education requires teachers who are prepared to educate students in another language. It takes time to train, certify and hire teachers, and that's just the beginning of the challenge. Bilingual education isn't just about teaching a language — it's about using the language to teach other subjects. Doing it well requires coordinating instruction with other teachers who might not be bilingual, or might not be using the same material. It takes time to work these things out.

Because California has so many students who already speak another language at home, a few quick steps were possible. For example, a plan had been debated for years to create a California Seal of Biliteracy to honor high school graduates who demonstrate literacy in two languages. Many other states offer similar designations. (Earning this seal on your diploma also helps your school, as the accomplishment has been incorporated into the California School Dashboard for College and Career.)

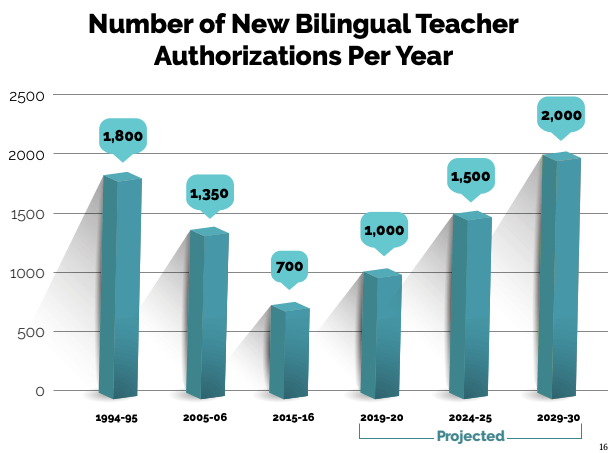

The State Board of Education defined a Roadmap in mid-2017 to clarify how it intends to support better policies related to language learning. This extended on efforts to develop grade-level language-learning standards and to coordinate county-level work to support language specialists. The Global California 2030 project set a goal of making half of California students bilingual by 2030, partly by rebuilding the state's pipeline of bilingual teachers, which had shrunk dramatically under Prop 227.

Connecting to Learn More

School district offices and county offices of education are good sources of information about schools in your area with a focus on language learning. In addition there are some nonprofit organizations worth checking out, including these:

- The California Association of Bilingual Education (CABE) holds an annual conference that brings together educators, school leaders, academics, curriculum providers, parents and advocates.

- Californians Together consistently advocates for policies to support bilingual education. In 2017 it released a useful report about the shortage of bilingual teachers.

This is an exciting time for language development in California. The repeal of the English Only policy has made it possible for school districts to be ambitious about creating schools and programs to develop multilingual students. Expansion of early education programs in the state seems likely to offer a moment for choices about whether and how to include multilingual elements.

Updated October 2019

Tags on this post

English learners Bilingual educationAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Denise Dafflon September 17, 2019 at 1:03 pm

Californians Together consistently advocates for policies to support bilingual education. In 2017 it released a useful report about the shortage of bilingual teachers.

Jeff Camp - Founder October 8, 2019 at 10:25 pm