Vouchers: A Dangerous Choice?

"Government" Schools

"For too long, countless American children have been trapped in failing government schools." With that phrase in the State of the Union address, President Trump lit the fuse of yet another public policy debate on the direction of public education.

He is supporting the Education Freedom Scholarships and Opportunities Act, a bill that would create a $5 billion annual federal tax credit to encourage the growth of private, religious and home schools at the expense of support for other forms of school choice involving public schools.

Are Vouchers the best choice to improve our schools?

This post explains some of the different ways that school voucher programs work, and what is known so far about their effects on children and communities. Politics aside, the question we should be asking is whether vouchers and education tax credits are the best strategy to improve education for low income students.

If you have limited time, here's the spoiler: There are much better options than vouchers to help low income students. The idea is not new, and California has rejected voucher proposals several times. Read on for details.

What are school vouchers?

In the context of education, vouchers are government-funded coupons good toward payment of tuition at private and religious schools. If you trace the origin of the word “vouch” to the 1690s, a voucher was a “receipt for a business transaction.”

Education vouchers are used in eighteen states. Some states also use tax policies to support private and religious education. The simplest of these policies is a tuition tax deduction, which allows taxpayers to reduce their taxable income by the amount they pay for private education costs. (Four US states allow such deductions.)

A tuition tax credit is an even more aggressive policy — it counts money paid for tuition as if it were used to pay taxes. (Five US states offer tuition tax credits.)

Deductions and tax credits are more valuable to people with higher tax liability than to those who pay very little taxes or none at all. A related idea is a tax credit scholarship, offered in varying forms in eighteen US states. This provides a tax credit to someone who donates to a non-profit that provides scholarships for private school.

Another voucher-like approach is an Education Savings Account, used in five states with varying rules. Here is how this works: Parents get a deposit of public funds which can be used to pay for non-public school education or to pay for educational services such as private tutoring, online programs, and extracurricular activities. According to the National Education Policy Center, these are “designed to, among other things, work around state constitutional prohibitions preventing using public money to fund private schools, particularly religious schools.”

What is the history of school vouchers?

Starting in the 1950s, economist Milton Friedman argued that market forces could help create better and more efficient schools. Given a choice, he argued, parents would enroll their children in the school that best suits them — presumably the best school. As a mechanism for putting this competition into practice, he suggested that students be provided vouchers toward payment for their education at any school, including private schools. The idea found favor with free market proponents, religious school leaders and think tanks.

Vouchers also found favor with segregationists. The timing of Friedman's proposal coincided with the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which required desegregation of public schools. The desegregation order triggered a wave of white flight to private schools, which were not subject to the ruling. To thwart the law, some southern states began issuing tax-funded tuition vouchers, which were accepted at private segregated schools.

School Choice Options

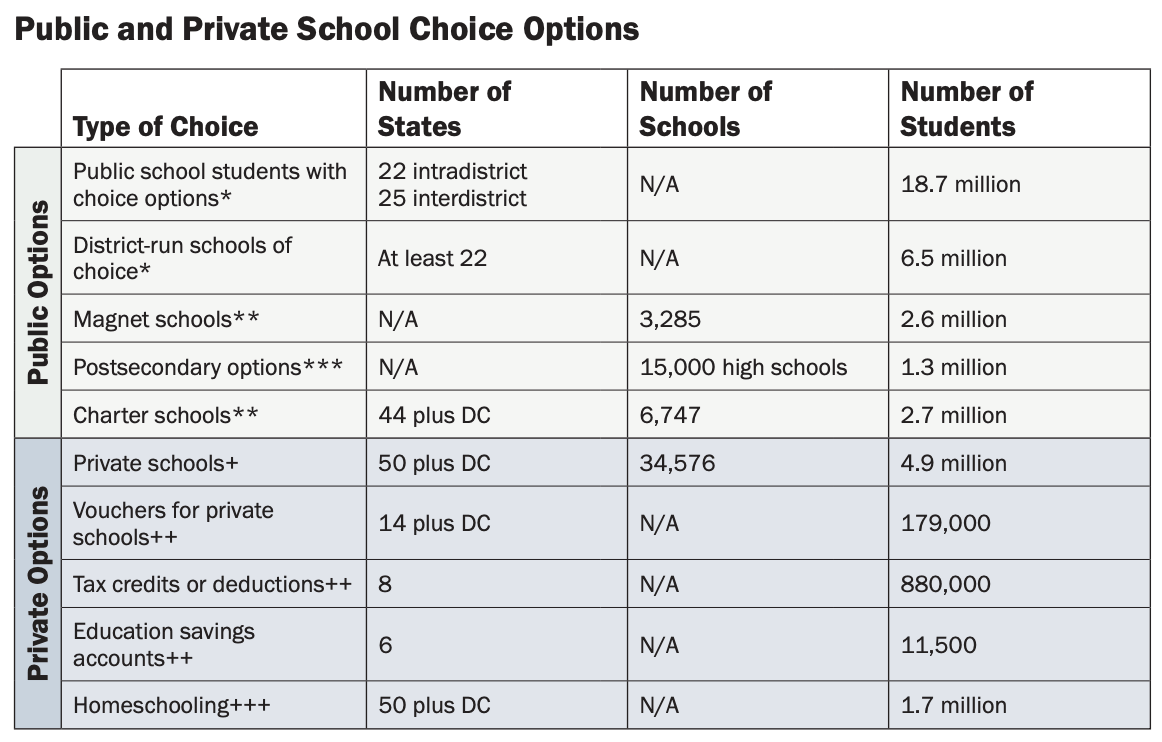

Although there is lively popular support for the general idea of school choice, voucher and voucher-like programs are a very minor mechanism for providing it. Most private school students attend a school affiliated with a religion. Most state constitutions, including California's, currently prohibit the use of taxpayers' money to support religious-affiliated schools. (The extent of this prohibition is scheduled to be reviewed by the US Supreme Court in 2020 in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue.)

Instead of vouchers, most states and districts have opted to deliver school choice through non-sectarian public charter schools, magnet schools, and open enrollment lotteries that allow students to enroll in schools other the one nearest their home. About a tenth of students in California attend a charter school, and in this state there are significantly more students in charter schools than in private schools. The Learning Policy Institute report Creating Quality School Choices for All America’s Children provides some insight on the issue of school choice, observing that “evidence shows that simply providing choices does not automatically provide high-quality options that are accessible to all students or improve student learning.”

Source and notes: Darling-Hammond, L., Rothman, R. & Cookson, P. W., Jr. (2017). Expanding high-quality educational options for all students: How states can create a system of schools worth choosing. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. For full report and footnotes see page 5.

Source and notes: Darling-Hammond, L., Rothman, R. & Cookson, P. W., Jr. (2017). Expanding high-quality educational options for all students: How states can create a system of schools worth choosing. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. For full report and footnotes see page 5.

Polls show that public charter schools enjoy broad public support. There is considerably less public support for school vouchers, and significant opposition to them.

Are voucher programs successful?

Setting all of that aside, is there evidence that voucher programs deliver stronger educational outcomes for students than traditional schools or charter schools?

The short answer is no. There have been many studies of voucher programs, most of them sponsored by religious orders or pro-voucher organizations. Early small-scale experimental programs seemed to suggest almost miraculous results, but those findings have not survived broader examination. More recent studies indicate that vouchers are not the silver bullet.

- In 2011, the Center for Education Policy released a ten-year study of voucher outcomes, concluding "vouchers have had no clear positive effect on student academic achievement, and mixed outcomes for students overall" .

- In 2015 the National Bureau for Economic Research (NBER) followed up with a study of similar breadth. While allowing that there have been cases where vouchers have made a positive difference for some students, the authors also noted evidence of negative effects. “A perhaps surprisingly large proportion of the most rigorous studies suggest that being awarded a voucher has an effect that is statistically indistinguishable from zero.”

School vouchers can, however, have a significant impact on the finances of churches. In 2017 NBER found that in Milwaukee "vouchers are now a dominant source of funding for many churches; parishes in our sample running voucher-accepting schools get more revenue from vouchers than from worshipers.

Do voucher programs hurt?

Sometimes. A 2016 study by the Brookings Institute, On the Negative Effects on Vouchers, found that students in voucher programs in Louisiana and Indiana scored lower on reading and math tests than similar students who remained in public schools. The magnitudes of the negative impacts were large. Studies in Ohio also indicate negative effects. An updated analysis of results in Louisiana echoed the finding in 2019.

A 2017 study by the National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (OSP) looked at the District of Columbia Opportunity Scholarship Program, which was created by Congress to provide tuition vouchers to low-income parents who want their child to attend a private school. After one year, the OSP had a “statistically significant negative impact on the mathematics achievement of students offered or using a scholarship. Reading scores were lower but the differences were not statistically significant.”

Limited Research on Education Savings Accounts

According to the National Education Policy Center, research on education savings accounts is very limited. “ESA programs embrace privatization and non-transparency by design. Accountability systems are absent, and data are limited; the lack of data and reporting will impede research on how these policies affect students, schools, and states.”

They add that the best evidence available about the efficacy of state-subsidized private education is probably the research on conventional voucher programs.

While a 2019 report on Florida tax credits found that participants were more likely to go to college, a review of this research found that it provides little guidance for policy and practice. It did not measure academic benefit and it had a problem with selection bias. “The study’s attempt to match students resulted in the comparison group having two to three times more students receiving reduced-price lunch. “

What Works?

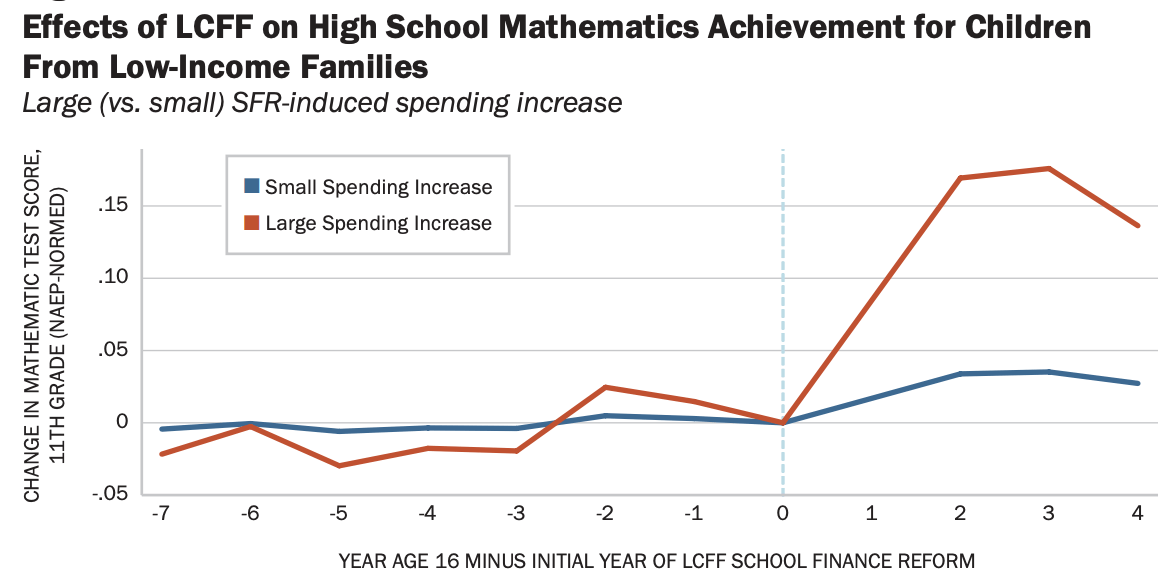

Evidence is piling up that in schools we get what we pay for. A 2016 study by the nonpartisan National Bureau of Economic Research examined ten years of data and found that sustained increases in spending in low-income school districts were associated with increased student achievement.

The Learning Policy Institute report How Money Matters for Schools (2017) concludes that “Recent studies have invariably found a positive, statistically significant relationship between student achievement gains and financial inputs.” They found that resources that cost money are positively associated with student outcomes. These include smaller class sizes, additional instructional supports, early childhood programs, and more competitive teacher compensation.

A 2016 international study known as PISA points to strategies that have been shown to improve educational outcomes:

- Rigorous and consistent standards in all classrooms.

- Investing in high quality teachers and school leaders.

- Providing additional resources to support at-risk students and low performing schools.

- Providing early education, after school support, health and counselors.

- On-going analysis of what works and what needs to be improved — focusing on high need students.

Additional research shows that giving kids a well-rounded education that includes the arts, physical education, and summer school are also successful strategies.

The Bottom Line

Vouchers should not be on the list of the best strategies for systemic educational improvement. There are better options. In many ways, proposals to use public money for private and religious schools are a distraction from more successful education reform strategies. By reducing funding for public education, they can actually harm public schools.

What are your thoughts? Let us know at [email protected]

Tags on this post

Charter schools School choice VouchersAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Briana Mullen February 12, 2020 at 10:49 am