What Happens When Teachers Go on Strike?

California's Education Shutdown

Teachers in America's second-largest school district went on strike for a week beginning on Monday, January 14, interrupting the education of over 600,000 students in Los Angeles Unified. In February teachers in Oakland Unified followed suit.

A Wave of Strikes

These strikes had loomed for months, and education leaders across America watched with interest. Since the 1970s, teacher strikes in America have been rare, but in 2018 a wave of strikes, walkouts, sick-outs and other actions disrupted schools in Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia, Colorado and elsewhere. The protesting teachers have used red T-shirts and banners, and organized under the hashtag #Red4Ed, but the protests have moved beyond politically conservative "red" states and cities. In December, teachers at Oakland High School staged an unauthorized one-day strike, setting the stage for district-wide action.

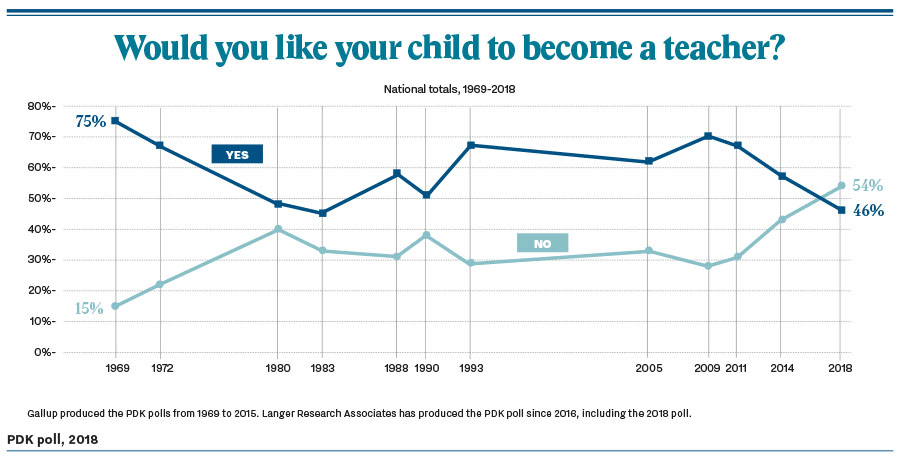

These strikes and demonstrations signal growing discontent among America's public school teachers. The appeal of the teaching profession has been declining. In 2018, for the first time surveys indicated that a majority of Americans don't want their kids to become teachers.

"Fifty-four percent of parents would not like one of their children to take up teaching in the public schools as a career, a majority response to this question for the first time since we began asking the question in 1969." Source: PDK Poll, 2018. Click chart to view source.

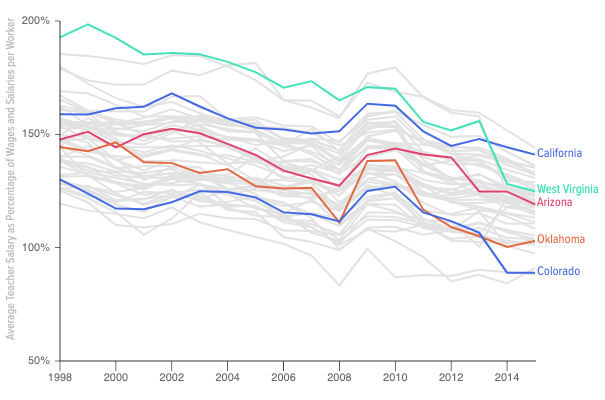

"Fifty-four percent of parents would not like one of their children to take up teaching in the public schools as a career, a majority response to this question for the first time since we began asking the question in 1969." Source: PDK Poll, 2018. Click chart to view source.Money is an important contributing factor to the declining attractiveness of teaching. Over decades, teacher pay across America has failed to keep pace with the growth in salaries for college-educated workers. The chart below shows teachers' income per person as a percentage of average income per person in each state. In the great recession, teachers were more likely than other workers to remain employed. When the recession ended, teachers' relative pay continued to slide.

Average teacher pay as a percentage of average pay of all workers.

Average teacher pay as a percentage of average pay of all workers.Historically, teacher pay significantly exceeded typical wages per capita. This premium has eroded over time, though less in California than in most states. Source: EdSource States In Motion project. Click chart to view source.

Many of the strikes and actions in 2018 were powered by teachers who had just reached the end of their rope. Leaders of teachers unions are now operating in uncharted territory, partly because a Supreme Court decision changed the rules for teacher unions in 2018. Until then, teachers in California and many other states were generally required to pay "fair share" fees to the union that negotiates for their interest in collective bargaining. The Janus decision disallowed these fees, making each teacher's contribution to their union a voluntary choice.

Will teachers feel better about supporting unions that represent them if they see evidence of conflict or evidence of collaboration? Contract showdowns in 2019 will set precedents that affect negotiating patterns for years to come.

What Are the Issues?

The collective bargaining agreement between a school district and its teachers union is usually known as "the teacher contract." Among many other things, the contract defines the rules under which teachers work and the "salary schedule" by which they are paid.

Both sides negotiating the contract must adhere to the rules of, well, math.

Both sides negotiating the contract must adhere to the rules of, well, math. When districts and unions have difficulty reaching agreement, a detailed conflict resolution process exists to help break through. The ultimate responsibility for providing public education lies with the state of California. In the rare cases when a district has made commitments beyond its ability to pay, the state has stepped in, replacing the school board with a state-assigned administrator. It has happened only rarely. Nobody likes that movie.

School district operating budgets are complicated, but the main drivers aren't mysterious: students, adults, and salaries. In California, the state allocates dollars to districts based on attendance — the number of students who actually show up. Districts receive a little more money to support students that are learning English, living in poverty, or in foster care. These rules are known as the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF).

Most of the expenditures of a school district go to salaries and benefits, which are negotiated in the contract. Recently, however, the cost of pension benefits has been climbing quickly, crowding out funds for lots of things, including teacher salaries. Districts must also be mindful of their obligation to provide for the education of students with special needs. State and Federal funds for special education have not kept pace, and districts now are paying twice as much as they did a decade ago to fill the gap.

Part of the conflict in Los Angeles arose from disagreements about how money is used. Is it best to commit to higher wages for teachers, even if that means hiring fewer of them and putting up with larger class sizes? Or should there be limits on class sizes, even if that makes the math hard to square? What's the right amount of money to set aside for a rainy day, and how do you know when it's time to dip into the money set aside?

These are difficult questions, and getting the answers wrong can do tremendous harm. Cautionary tales abound, especially in places where school enrollment is declining, like Oakland, Richmond and Watts. Even where enrollment is flat, math is unforgiving. In 2017 Sacramento City Unified avoided a strike by making contract concessions that it later found it could not afford, and now the district is in crisis.

What Happens Next?

When teachers go on strike, bad things happen. School attendance is mandatory in California, and many families rely on school as a safe environment for their children during the work day. The Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) declared that schools would open during the strike, as did Oakland, in both cases hiring substitutes to care for the students that showed up to school. In an interview LAUSD Superintendent Austin Beutner said “Schools will be open because we serve a million meals a day to kids living in poverty. Because we have families who rely on us to make sure their children are safe, while they earn a living. Schools will be open because the children will be learning. It may be a different type of learning.”

When families keep their kids at home, it further aggravates a school district's financial challenges because school funding is based on attendance. Each day a student misses school the district loses about $75 in revenue from the state. (Teachers that strike forgo their pay, too.)

In general, polls suggest that the public supports teachers in a strike, but a lot is unknown. The 2019 strikes in Los Angeles and Oakland each lasted a week. Thirty years earlier, the teacher strike in Los Angeles lasted nine days.

Is There a Long-Term Solution?

The core issue is money. California's education system has long been among the lowest-funded in the nation when the cost of living is taken into consideration. School districts have little control over the amount of money that they have to bargain with; the amount they receive is not determined by the school board, but by California's voters and the volatility of the stock market, which tends to exaggerate both upswings and downswings in the economy. Bear markets drive major cuts that can take years to repair; it took two tax measures and eight years for the California education budget to recover from the great recession.

There are some reasons for hope.

The Budget Blueprint. Assemblymember Phil Ting, chair of the Assembly Budget Committee, acknowledges in his 2019 budget blueprint the need to “help districts plan for the future...by developing a long-term funding mechanism for schools.” Governor Newsom's proposed budget for 2019-20 included significant investments in education, including $3 billion to relieve the overhanging burden of an underfunded pension system.

A Clearer Funding Target. Beyond 2020, what is the right amount of funding for education? Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi has again introduced a bill, AB 39, to provide an answer: bring California to the top ten in the nation in per pupil spending. The bill proposes a funding target under California’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) to increase the state’s K-12 funding by $35 billion over an unspecified number of years. But the bill has no funding mechanism.

"Top Ten" Pressure from Education Advocates

The major education advocates are upping their game to make the "top ten" vision stick. Volunteers from around the state, organized by the California State PTA, have visited legislators in Sacramento asking for a long term plan to increase education funding to match levels in the 10 highest funded and achieving states.

The PTA also passed a resolution at its annual 2018 convention, calling on the legislature and the Governor to "enact legislation that allows the state to invest in education including early childhood education at the levels of our highest achieving states.”

The California School Boards Association and the Association of California School Administrators seek a Constitutional Amendment to move California to the top 10 states in per-pupil funding as part of a campaign for Full and Fair Funding for California schools. The California Teachers Association also supports moving California to the average of the top ten states in per pupil funding.

The strikes in Los Angeles and Oakland generated visibility and support for increased education funding, but it's important to acknowledge the size of the gap.

How Much Will It Cost?

Generating enough money to reach the level of the top 10 states is not simply a matter of shifting some money from one budget line to another.

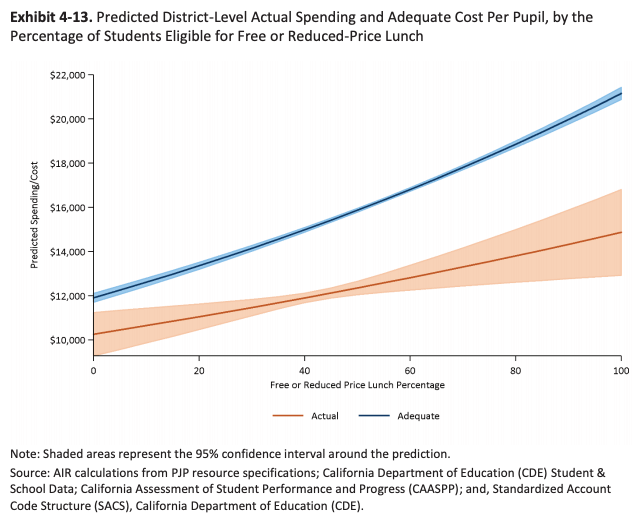

The recent Getting Down to Facts II study evaluated California's funding for education and concluded that “an additional $25.6 billion or 38 per cent above actual spending is necessary for all students to meet the standard goals set by the State." That's a gap equivalent to about $4,050 per student.

The chart below shows how much more money is needed to reach adequate funding — with higher costs for children from poor families.

This $25 billion shortfall represents only the additional amount needed for California school funding to reach an "adequate" level. What would it cost to reach the level of the top 10 states as targeted in Assemblymember Muratsuchi’s bill? A lot more. He is aiming for an additional $35 billion.

What Are the Long Term Options?

To provide California's students with an adequate education will require billions of dollars, and that means taxes. There are many options, and the main ones are summarized in Ed100 Lesson 8.9, including a "split roll" property tax that would generate about $4 billion a year for schools, far short of the $25 or 35 billion targets.

It's important to recognize the scale of this challenge. There are over six million students in California's public schools. As a rule of thumb, a tax that raises $1 billion is equivalent to just $160 per student. This rule of thumb can help put things in perspective. Sure, a billion is a big number in the abstract, but California's funding for schools is many billions short of adequate. No one solution is sufficient on its own.

What Happens if California does nothing?

Teacher strikes and protests are a symptom of deeper problems that have been gradually undermining the effectiveness of California education and the attractiveness of the teaching profession. Already, the state is wrestling with major teacher shortages, especially in special education. If California allows teaching to continue become a less attractive profession, students and families will suffer for it, and California children will continue to lag the nation in academic success.

Originally published Jan 10, 2019.

Updated Jan 22, 2019; Feb 5, 2019; March 1, 2019.

Carol and Jeff collaborated on this post.

Tags on this post

Collective bargaining Unions StrikeAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

tamara_hurley February 27, 2019 at 4:36 pm

However, it was my understanding that all collective bargaining contracts remain intact until they expire. I followed the links in your post, but none of them actually addressed the contracts during state takeover. Could you provide links to more detailed information regarding the consequences of school district insolvency?

Jeff Camp February 27, 2019 at 5:53 pm

Jennifer B February 12, 2019 at 11:21 am

Jeff Camp February 12, 2019 at 12:17 pm

Jeff Camp January 23, 2019 at 12:55 pm

Alice Donawerth January 11, 2019 at 3:04 pm

Jeff Camp January 15, 2019 at 12:28 pm