California state budget for education, 2024-25

Juggling a huge budget deficit. Education funding protected.

California’a proposed state budget for 2024-25 is an excellent example of Benjamin Franklin's famous maxim, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

According to the California Department of Finance, the proposed state budget for 2024-25 starts with a deficit of about $38 billion. It’s a big number (about $1,000 per Californian), but the Governor argues we are in a good position to weather it thanks to a decade of preventive budget planning. Here’s how:

Rainy Day reserves. In 2014, California voters overwhelmingly approved (69.1%) a ballot measure that enabled state leaders to set aside meaningful rainy day reserves. Over the last ten years, the state has steadily built reserves in two separate reserve accounts, one for the general budget and one specifically for education.

To dip into reserve funds, California will declare a budget “emergency”

The Governor’s proposed budget for 2024-25 calls to use this stabilization mechanism, drawing $13.1 billion from state reserves (about half the amount available) to help balance the budget. In order to do so, the governor must declare a budget emergency and the Legislature must pass a bill by majority vote. The declaration can happen in tandem with the vote.

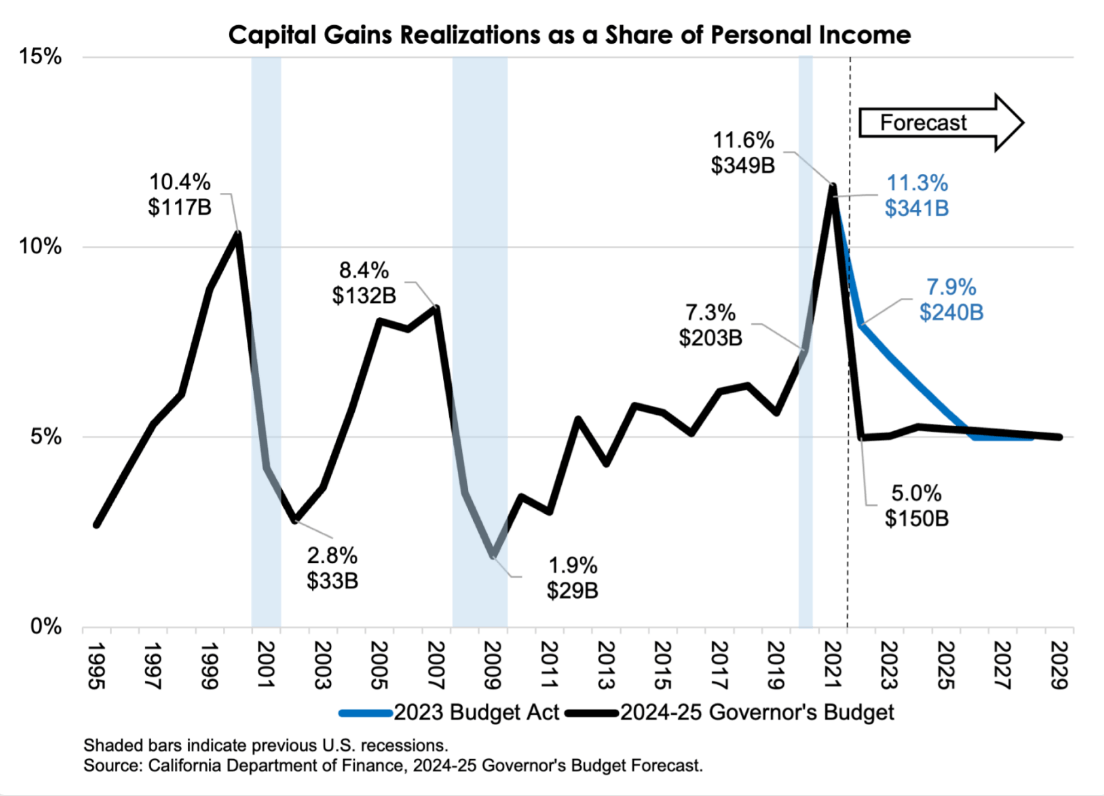

Prudent spending. In 2021-22, the stock market had done well. People had made profits on investments and paid taxes on the capital gains. California was riding high on a huge wave of unexpected tax revenue. But what goes up can also go down.

Last fiscal year (2023-24), California’s state tax revenues fell 20% according to the California Legislative Analyst Office (LAO). When people lose money in the market, they incur capital losses that offset their taxable gains. This recurring boom-bust cycle is a big reason why Californians voted overwhelmingly to create rainy day reserve accounts — it makes sense to bank some windfalls. Similarly, rather than cut to the bone with every downturn, it makes sense to cushion the harm by drawing on reserves.

Last year’s budget anticipated the bad news, adding money to the state’s rainy-day funds and spending with caution. The Governor vetoed nearly $19 billion in spending last year with a boilerplate explanation:

“With our state facing continuing economic risk and revenue uncertainty, it is important to remain disciplined in considering bills with significant fiscal implications, such as this measure.”

To avoid turning temporary shortfalls into permanent ones, many projects were crafted as one-time expenditures, so that they could be deferred or cut back if necessary. We might hear a lot about discontinued programs in the year ahead.

In summarizing the proposed budget, the Newsom administration emphasized that billions were returned to taxpayers as refunds during the boom years. Some had to be returned, legally, because of the spending cap voters passed into the state constitution as an initiative in the 1970s. Governor Newsom is beginning to make the case that this convoluted system should be rethought, giving more room for rainy day reserve systems to function at many levels.

Budgeting while blindfolded

The processes involved in tax collection and budget planning have been hammered out over years of experience. In 2023, the processes were badly disrupted.

Here’s how it’s supposed to work. Each January, the Governor produces a draft budget based on a forecast of the year ahead. Taxes are ordinarily paid and filed by April 15, which gives California’s state leaders the information and time they need to revise the draft budget in May and finalize it by June 15, the constitutional deadline.

Tidy columns of numbers invite a sense of certainty

But that didn’t happen in 2023. Partly as a response to wildfires and floods, the IRS delayed the filing deadline for the 2022 tax year in 55 out of 58 counties in California, ultimately until November of 2023. This left everyone in the dark about what tax revenue to expect.

Tidy columns of numbers invite a sense of certainty, as if they perfectly represent reality. But budgets by their nature always involve forecasts, estimation, and judgment. It’s normal and healthy for experts to reach different conclusions, especially with incomplete data. For example, in December 2023 the state’s independent legislative analyst (LAO) estimated the state deficit at $68 billion. In the January budget, the Department of Finance set the number at $38 billion. In subsequent analysis released in January 2024, the LAO refined its guidance, but still recommended at least $10B more in cuts than the Governor had budgeted.

How will California close the deficit?

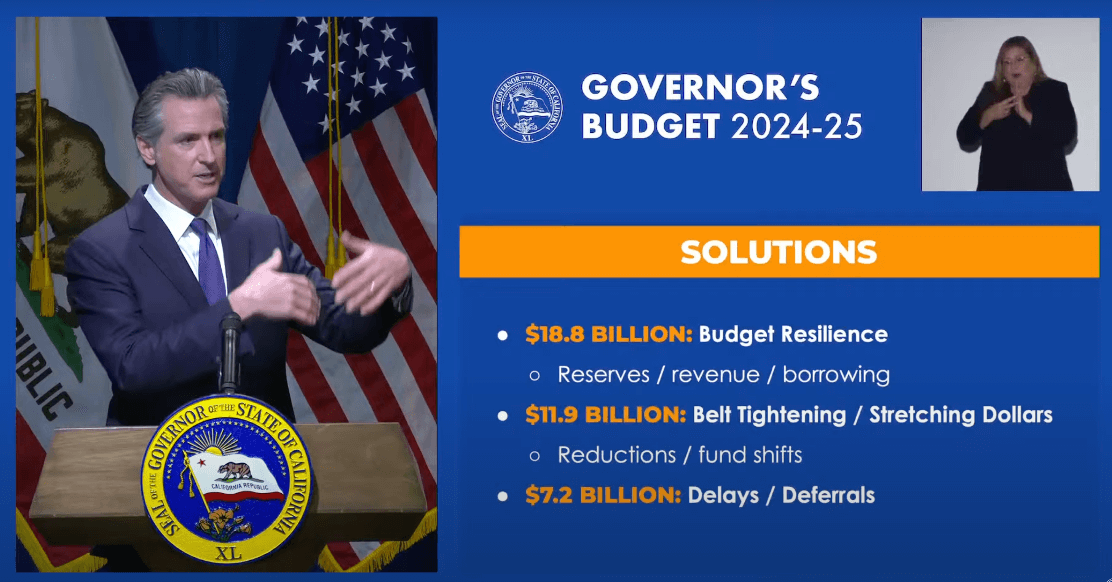

California’s constitution requires the state to have a balanced budget. The Governor’s proposal uses a variety of strategies to make ends meet:

- Draw on reserves ($13.1B in the governor’s 2024-5 proposal)

- Borrow internally ($5.7B)

- Reduce spending ($8.5B)

- Delay spending ($3.4B)

- Reallocate funds ($5.1B)

- Defer obligations to the next budget cycle. ($2.1B)

The education plan for the year ahead includes some important investments in education, all of which require funds. Drawing on reserves isn’t just a theoretical matter — there are real programs at stake and tradeoffs required. This post will examine some of them in a bit, but first we’ll put it in context.

The Governor’s presentation of the budget is lengthy and detailed. Click the image below to watch it on YouTube.

State budget basics: the General Fund

The state of California operates on a fiscal year that begins in July. Each January, the governor proposes a state budget based on a forecast of how much the state will take in through taxes collected in the state's General Fund. Under public scrutiny and comment, the Governor’s proposal is formally revised in May. A budget bill must be passed by the legislature and signed by the Governor by June 30.

Multiple taxes in combination make up the revenue of the state general fund. The mix of sources does not tend to change a great deal from year to year. Here’s the big picture for 2024-25 in the Governor’s proposal:

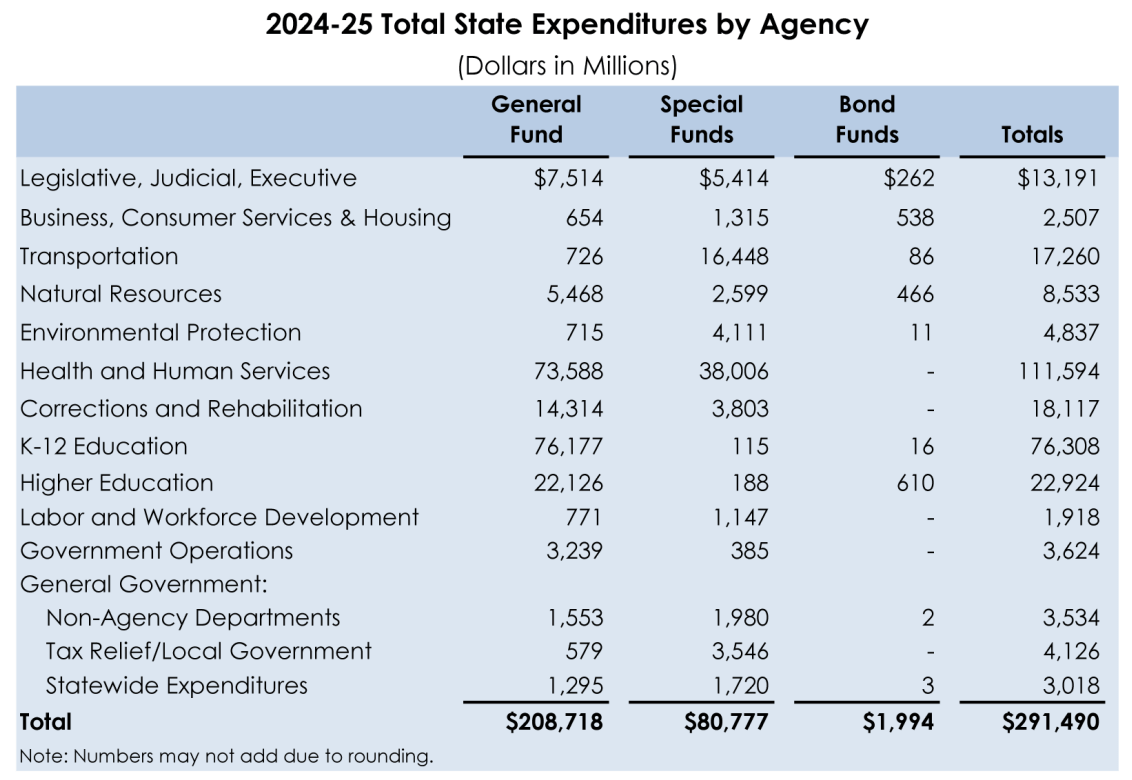

Virtually all education expenditures in the state budget are included in the state’s General Fund. The state maintains Special funds but they are mostly not related to education:

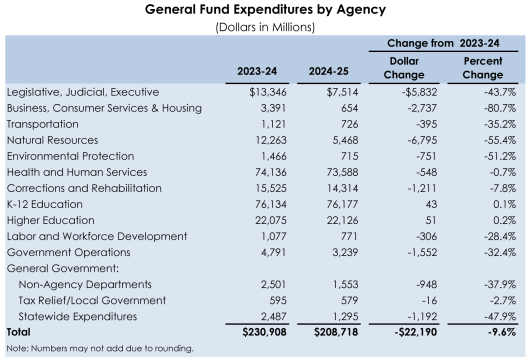

Where are the cuts coming from?

The Governor’s overall proposed budget for 2024-25 calls for 9.6% in overall cuts vs. the prior year, but virtually no cuts to K-12 education or higher education. The budget uses withdrawals of $5.7 billion from the education reserve accout to stabilize funding for schools and community colleges. Should the financial picture get worse during the spring, look forward to significant debates over how to balance the budget.

How is the education share of the state budget determined?

The portion of the state General Fund that goes to K-12 schools and public community colleges each year is determined by formulas that voters enshrined in the state constitution by passing Proposition 98 in 1988.

Oversimplifying heroically, this formula usually requires that about 40% of the state General Fund should go to K-14 education. The formula includes many factors, including how well the economy is doing, whether there are more or fewer kids showing up to public school, and changes in the cost of living.

In theory, the legislature can allocate more of the general fund to education than this formula requires. In practice, it rarely does. The governor's proposed budget for 2024-25 allocates about 39.5% of the general fund to education. This reflects the continued implementation of universal Transitional Kindergarten and the implementation of California’s guaranteed funding for arts education.

What sources of revenue fund public education?

State taxes are not the only source of money for public schools. In fact, in 2024-25 the state budget is only about half of the story (51%) when it comes to funding for K-12 education in California.

State revenue as a fraction of school funding has varied over time, as shown in the chart above. The level of funding for education from the total of all sources is a reflection of society's collective economic effort to provide funds for schools. Put simply, we aren’t trying very hard to fund schools.

In addition to state taxes, there are three important sources of funding for public schools.

Property taxes. Decades ago, local property taxes were the main source of revenue for public schools. Nowadays, they usually contribute about a third of the money for K-12 education. Property taxes for education are not part of the state budget, but estimates are included in the accounting of Proposition 98 budget figures.

The combination of state general fund taxes for education and local property taxes for education is known as the Proposition 98 budget. Since 1988, the California state constitution has guaranteed that public schools and colleges (TK-14) must receive funding from the state budget at a level per student defined by the provisions of Proposition 98 and the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF).

Federal funds. Federal funds, which are not part of the state budget, usually contribute less than a tenth of the cost of schools in California, but these are not normal times. California has received $15 billion in federal pandemic relief funding for things such as mental health and trauma needs, learning loss, safe return of all students in-person, full-time school and the teacher shortage. Federal funding can be fickle, and education leaders worry that when remaining relief funds are exhausted, their disappearance will add to the challenges.

Local funds. Local funds like parcel taxes and donations aren't considered in the state budget process. In most places they don’t contribute significantly to school funding.

How is the money in Prop. 98 allocated?

The rules that allocate funds from Prop. 98 to school districts are known as the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Money is allocated from the state general fund and from property taxes received based on the number of students who show up to school and the characteristics of those students. The formula directs more money to districts to support students who are low income, in foster care, and/or learning English. (There’s more to it — read Ed100 Lesson 8.5.)

|

K-12 education funding by the numbers, 2024-25 Governor's Budget |

|

|---|---|

|

Funding from state taxes for K-12 |

General fund: $76.4 billion in 2024-25 $79.5 billion in 2023-24. |

|

Funding from property taxes for K-12 |

As part of the budget process, the state forecasts and plans for Proposition 98. This requires a forecast for property taxes, which are in most ways separate from the state budget. Proposition 98 funds both K-12 schools and community colleges, and the figures in the Governor’s budget conflate the two. Without saying so directly, the implied split in the 2024-25 Prop98 forecast is probably $95.26B for K-12 and $13.84B for community colleges. |

|

Prop 98 K-12 per-pupil funding |

The governor’s state budget states that 2024-25 funding per student in attendance will be $17,653 Proposition 98 General Fund and $23,519 per pupil when the contribution of all sources including property taxes are included. |

|

LCFF cost-of-living adjustment |

0.76 percent increase. The budget does not spell out exactly how, but it calculates that the combined effect of funding changes, population changes, and contributions to the reserve fund imply a small cost of living increase of less than one percent. |

Per-pupil funding changes this year

Ready for something nerdy? Enrollment in California public schools is declining in 2024-25, but the decrease doesn’t trigger a decrease in state funding. Here’s why.

The Prop. 98 funding guarantee has three different tests to determine the level of required funding for public education. Two of those tests look at projected revenues in combination with projected enrollment. But a third test is based only on general fund revenue. This year the budget calculations use that test because it yields more funding. Thus, the percentage of General Fund revenues is not reduced to reflect declining enrollment, which increases per pupil funding.

Yes, it's complicated. And also: Yippee? Or Whew, at least?

What does inflation do to school funding?

There are two major ways to look at the growth of Prop 98 funds over time. The official budget presents it as in the chart below, highlighting the dramatic increase in dollars of funding over time.

Dollars are only good for what they can buy. Over time, inflation acts like a curved mirror: it makes historical numbers seem small and recent numbers seem big.

When adjusted to account for the change in purchasing power, Prop. 98 funding per student peaked in 2021-22… and isn’t all that different from 30 years ago:

Specifics in the budget

This post opened with some bullet point highlights from the proposed budget. We'll close with a few more related to education:

|

2024-25 Selected budget highlights for education |

|

|---|---|

|

Instructional continuity |

To provide students with needed instructional continuity including when facing challenges such as severe climate events, illness, or other barriers that impact attendance, the budget proposes changes to allow students to make up lost instructional time, thereby offsetting student absences, and mitigating learning loss and chronic absenteeism |

|

Attendance |

$6 million one-time Proposition 98 General Fund to support students’ attendance. |

|

State pre-school program |

$53.7 million to support reimbursement rate increases. |

|

Dyslexia screening |

$25 million to support training for educators to administer literacy screenings for students in kindergarten through second grade for risk of reading difficulties, including dyslexia. |

|

Math Frameworks |

$20 million one-time to develop and provide training for mathematics coaches and leaders who can provide training and support to math teachers. |

|

Pre-school Transitional K facilities |

Delays the 2024-25 planned $550 million investment to 2025-26. |

|

Zero-Emission School Buses |

Maintains $500 million one-time to support greening school bus fleets. |

|

Curriculum-Embedded Performance Tasks for Science |

$7 million one-time Proposition 98 General Fund increase of to support inquiry-based science instruction |

|

Nutrition |

An increase of $122.2 million ongoing to fully fund the universal school meals program in 2024-25, when Over 845 million meals are projected to be served. |

|

Cradle-to-Career Data System |

An increase of $5 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to support the California College Guidance Initiative. |

|

Broadband Infrastructure Grant |

An increase of $5 million one-time non-Proposition to extend the program through 2029. In addition to providing fiber broadband connectivity to the most poorly connected school sites, funding would also be available for joint projects connecting schools, local libraries and telehealth providers to high-speed fiber broadband. |

The budget process ahead

Throughout the first half of the year, committee hearings examine both the budget itself and education bills that might have an impact on the budget. Each of these pathways is a little different. (The California Budget & Policy Center, a non-profit organization, does a great job of explaining the distinction between these two paths.)

Tags on this post

Budgets LCFF PolicyAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Jeff Camp - Founder May 29, 2024 at 3:21 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder January 23, 2024 at 11:44 am

Elizabeth Keener January 16, 2024 at 1:04 pm

Jeff Camp - Founder January 17, 2024 at 5:13 pm