How the State Budget Affects Your School

Finding a Way

Every year, California creates a state budget and sets aside a major chunk of money for schools. How much? Who decides? Is it enough? Where does the money come from and how is it allocated?

Budget Basics

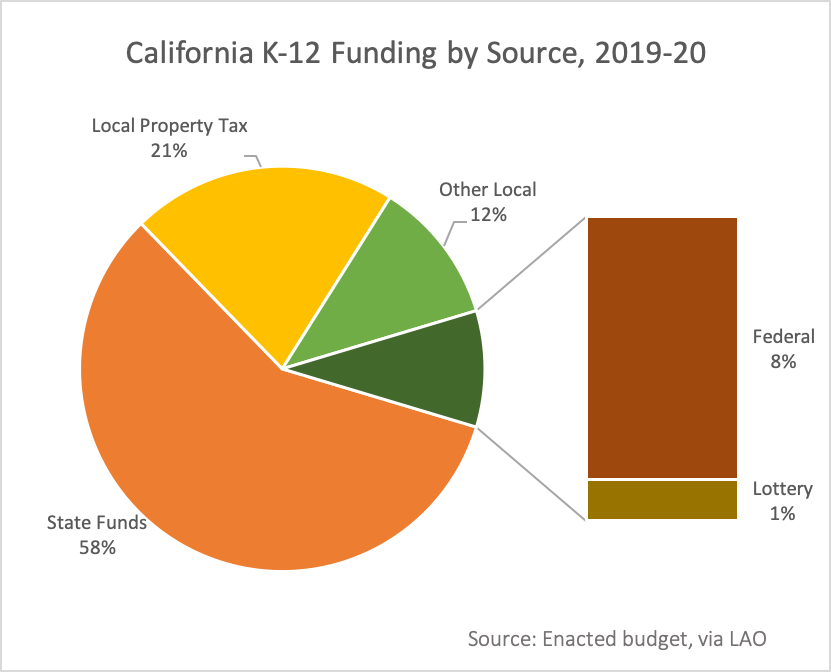

Let’s start with the basics. In many other states, most of the money for schools is generated by local property taxes. In California schools, property taxes are just one source of funds, and not even the largest. Most of the money comes from the state budget, which mostly comes from income taxes. (To learn more, click the pie chart.)

The budget process formally kicks off each January (see our post about it) with the Governor's budget proposal.

Remind Me Again about Education’s Minimum Guarantee

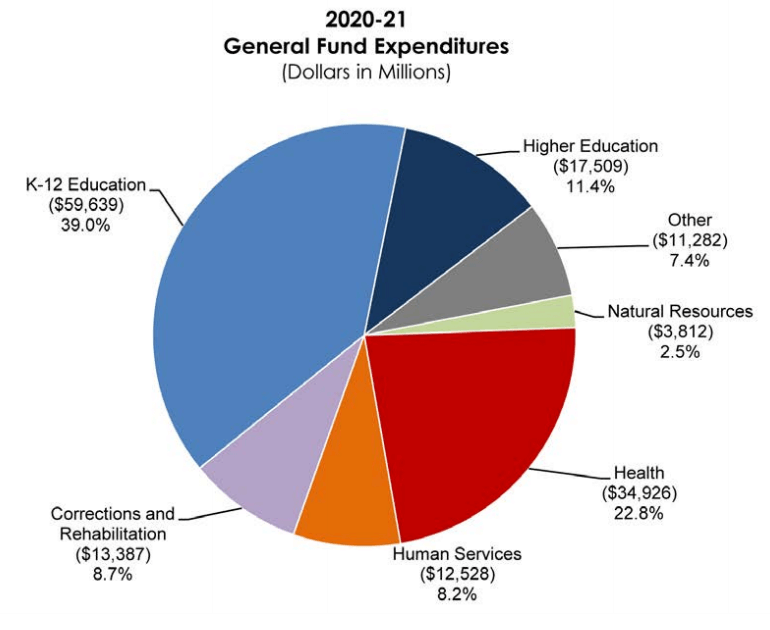

Education’s minimum share of the state budget is determined by a formula generally known as Prop 98, which guarantees that the total amount raised for education will reach a certain level. The general fund plays an important role — the K-12 education share of that budget usually ends up at about 40% of the general fund.

The Governor and the legislature have the power to spend more than that portion — but usually don't. Last year, in the 2019-20 budget, Governor Newsom was an exception, recognizing that pensions and other education costs had been growing at a faster rate than the minimum funding guarantee.

Some funds outside of the Prop 98 portion of the general fund are important for education, too. For example, the 2019-20 budget also included a one-time line item of $3.15 billion to help pay down local school districts' massive pension obligations. The 2020-21 proposed budget benefits from this pension relief but does not add to it.

Where Does the Money Go?

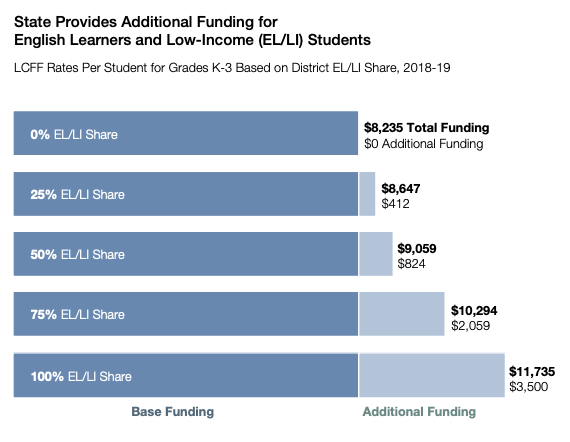

Most education funding is distributed to local school districts based on the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Districts with more needy students get more money. How much more? For a sense of scale, here's a chart of how the formula affected funding in 2018-19.

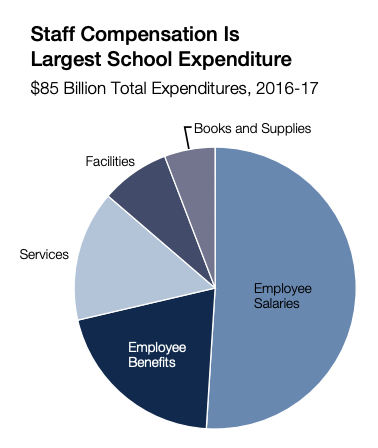

The bulk of this money pays for the staff costs of running schools — especially the salaries, benefits and pensions of teachers.

School districts — not the state — decide how LCFF money is spent. Your school district uses the Governor’s January budget proposal to create a local budget, making tradeoffs about class size, teacher salaries, counselors, nurses, social workers, arts programs and more.

With that said, some expenses are unavoidable. For many years, California's school system failed to set aside sufficient funds for teacher pensions, and now school districts are stuck playing catch-up. A portion of education funding this year will be used by your school district to pay for increased pension obligations and other ongoing costs.

State Policy Influences Spending

In addition to funding LCFF, the Prop. 98 portion of the budget funds a variety of other initiatives such as transportation and support for school staff. A big portion goes to special education. (You can find details on this funding here.)

School district spending is guided by state-adopted budget priorities. These include, for example, budgeting for a safe and supportive school climate, a full curriculum, improving student achievement and engagement, and implementation of state standards.

How Much Money Will Schools Get in 2020-2021?

In January of 2020, Governor Newsom launched the budget process. A few key numbers put it in context:

$12,600 per student. The Governor proposes to increase operational funding for K-12 education by $496 per student over last year to an average of $12,600. Most of this increase goes to pay for new programs in the budget beyond the LCFF allocation.

Remember — this is an average figure. Some districts will get more and some will get less, mainly based on the portion of students in poverty or learning English. This figure only includes the money used to operate schools, not to build or renovate them. (See page 69 of the budget statement for total expenditures from all sources.)

$84 billion. This is the total amount proposed for Prop 98, the funding committed to operation of preK-12 schools and community colleges. The calculation of the Prop 98 guarantee is complicated. See this primer from EdSource.

|

Major education budget proposals |

|---|

|

$1.2 billion augmentation to the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). For context, each $1 billion in the state budget is equivalent to about $160 per student — roughly the cost of a high school textbook. |

|

Approximately $900 million for educator recruitment and training. |

|

An increase of nearly $900 million for special education. |

|

$300 million for expanded supports and services for the state’s neediest schools. |

|

$300 million for the development of innovative community school models that support student mental health. |

|

$70 million to improve and strengthen school meal programs. |

The budget also proposes changes to improve fiscal accountability regarding the use of LCFF funds. You can find much more in the state's e-budget K-12 Summary.

Will Schools have Enough Money to Expand Programs for Kids?

Well, yes and no. This is basically a status quo budget for most schools. Not all districts will get the extra bump from the $496 per student increase in Prop. 98.

After paying for the increased costs of pensions and other ongoing expenses, many school districts will continue to have a hard time making ends meet. Each school district’s finances are different. Sacramento and Oakland schools, for example, are in deep financial distress while schools in Palo Alto are in a happier place.

Reducing Child Poverty: Beyond Education

Too often, education advocates focus narrowly on what’s in the education portion of the budget. The important link between poverty and student achievement falls off the radar. Let’s not do that here.

A slew of new research continues to confirm that children do better in school when their families are supported with additional income, food support, tax credits, healthcare benefits and stable housing. It’s not just the education portion of the budget that affects schools. What distinguishes highly successful education systems is how they support children and families.

A 2019 report from the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) reveals why this is so important in California:

- The child poverty rate in California still exceeds the rate before the Great Recession.

- Close to half of California’s children live in or near poverty.

- About 60 percent of students attending California public schools are eligible for free or reduced priced meals.

As we explored in Ed100 Lesson 2.2, how well children learn has a lot to do with how well they live.

The Governor's budget proposal includes significant investments that have a direct impact on child poverty, including investments in preschool, paid family leave, housing, income supports, health, and child care. You can find details in the budget sections below:

If you want to dig deeper, The National Center for Children in Poverty provides a 50 State Policy Tracker comparing state economic assistance programs to help low-income working parents succeed in making ends meet.

What Happens Next?

The Governor's proposed budget in January is not the end of the story. There are hearings throughout the first half of the year that look at both the budget itself and at the budget impact of education bills.

By May 14, the Governor releases a revised budget that reflects input and more up-to-date financial information.

By June 15, the Senate and Assembly leaders huddle with the Governor to hash out the final details and pass a balanced budget by a majority vote of both houses.

Want to know more about the budget?

State Budget

- Obviously, many organizations are examining the governor's budget proposal. Important early analysis is available from the Legislative Analyst (@LAO_CA) and the California Budget & Policy Center (@CalBudgetCenter).

- EdSource (@Edsource) provides daily news on education issues.

- The California State PTA (@capta_capitol) tracks legislation that affects children and families. You can join their monthly advocacy calls.

School District Budget

- The Ed100 LCAP Checklist helps you analyze education issues and participate in budget decisions in your school and school district.

- Your school district will provide budget information on its web site and is required to get input from parents and communities as the budget is prepared.

Tags on this post

Budgets FundingAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Caroline February 18, 2020 at 1:22 pm

Carol Kocivar January 26, 2020 at 5:03 pm

Jamie Kiffel-Alcheh January 15, 2020 at 9:24 pm

Is that because some schools receive more funding than others, based on how many impoverished students or other specially-funded demographics they have?

Jeff Camp January 22, 2020 at 3:40 pm