When teachers go on strike

Sometimes it's hard to find agreement

Throughout California, school districts and unions are negotiating salaries, benefits, and working conditions. It's a complicated dance with many elements: the financial health of the district, increased costs of living, comparative salaries and benefits, and more.

In This Post

What is a strike?

Are teacher strikes legal?

How common are teacher strikes?

What is a work action?

What do teachers and districts negotiate?

What is PERB?

What is an impasse?

What is fact-finding?

What is the collective bargaining process?

How does communication work during a possible strike negotiation?

What is the role of a school board in a teacher strike?

What is the role of PTA in a teacher strike?

This post explains what can happen if both sides cannot come to an agreement: a strike.

What is a strike?

A strike is a work stoppage intended to provoke a change in the terms of the relationship between employers and employees. Strikes are intentionally disruptive, and usually occur only when contract negotiations completely break down.

Because strikes do harm, laws have been created to avoid them. The negotiating parties (in education, unions and school districts) must participate in a negotiation process with a solution-oriented mindset (called good faith bargaining). This mindset must be used (and demonstrated through action) even when things start to turn south and outside help is needed to smooth things out, for example, during an impasse or fact-finding. (More about this below).

Can all teachers strike?

The laws that govern strikes vary from state to state. EdWeek reports that teacher strikes are legal in twelve states, including California. They are illegal in 35 states, and in three others there are no explicit laws or statutes.

Are teacher strikes rare?

Yes. Strikes are rare, but they appear to be on the rise. According to Becky Kolins Givan, Associate Professor of Labor Studies and Employment Relations at Rutgers University and author of Strike for the Common Good:

- There have been 92 strikes in 21 states since January 1, 2012.

- More than 672,000 teachers walked out, affecting 6.7 million students.

- Close to half of the strikes, 42, were illegal in the state where they took place.

In 2019, California experienced strikes throughout the state designed to highlight the state's chronic underinvestment in education. Conflicts about charter school policies also contributed to the strife.

Strikes do not happen overnight. There are many legally required processes in place to keep parties negotiating and avoid strikes. According to the California School Board Association (CSBA), the vast majority of districts get to agreement without assistance. About a tenth require mediation, and perhaps 1% of cases require fact-finding.

Work actions

Short of a strike, there are other actions that unions and their members may undertake to raise awareness, especially Work-to-Rule, Sick-outs, and Informational Picketing:

|

Work actions, defined |

|

|---|---|

|

Work-to-Rule |

Teachers follow their contract to the word with no extras. Teachers may not stay after school to help students, arrange field trips, assist with student clubs, and more. |

|

Sick-out |

Many teachers call in sick on the same day to shut down a school, several schools or an entire district. |

|

Informational Picketing |

A public demonstration by a labor union or its members to inform the public about a matter of concern. Teachers may hand out fliers or talk to parents bringing children to and from school. |

When do teachers and districts negotiate?

A typical teacher's contract is extremely complex and will contain agreements on most aspects of employment including:

- Total Compensation including health and welfare benefits.

- Working Conditions including length of the work day and year (although by law students must receive minimum instructional minutes and days), class sizes and any other duties that qualify for stipends.

- Job Assignments including transfers, promotions, layoffs and rehires.

- Dispute Resolution including processes to file grievances and commence work stoppages (no-strike clauses) and more.

Contracts are unique and vary from district to district. Whether a large and vastly complex district like Los Angeles (about half a million students) or a smaller one such as Amador (3,800 students), the agreements are likely to run hundreds of pages in length and contain many stipulations. It is likely that the parties will not agree on everything, and some differences may seem unresolvable.

In California, the Rodda Act, passed in 1975, requires the labor contract to be reviewed at least once every three years.

What is PERB?

In 1976, the California legislature created the Public Employee Relations Board (PERB) to mediate labor disputes and help bring them to resolution. At the same time, the legislature created specific steps and procedures to help parties come to an agreement. PERB's panel will decide the outcomes of certain labor grievances, but also finds mediators and appoints fact-finders, and issues reports when labor negotiations start to unravel.

What is an impasse?

In about a tenth of all negotiations, the parties are not able to reach agreement and one or both sides will declare an impasse. This means they are at a stalemate and need outside help to reach agreement. Once an impasse is declared, PERB steps in and appoints a mediator to keep the process moving. In most cases, the terms of the existing contract continue while the parties bargain, even if the existing contract has expired.

Fact finding

When a tentative agreement is not reached through mediation, the fact-finding process begins. Three people make up a fact-finding panel. The union and the district each select a panelist and a chairperson is provided by PERB. Both sides present their cases and the panel prepares to write a report.

If the fact-finding process results in agreement, the fact-finding report is usually not made public. If no agreement is reached within 30 days after the fact finding hearing, however, the panel issues an advisory recommendation. The fact-finding recommendations are submitted privately in writing to the parties and must be made public by the employer within 10 days of receipt.

Usually, the fact finding reports and its findings pressure the sides to reach agreement.

Very rarely, the union will strike.

Collective Bargaining

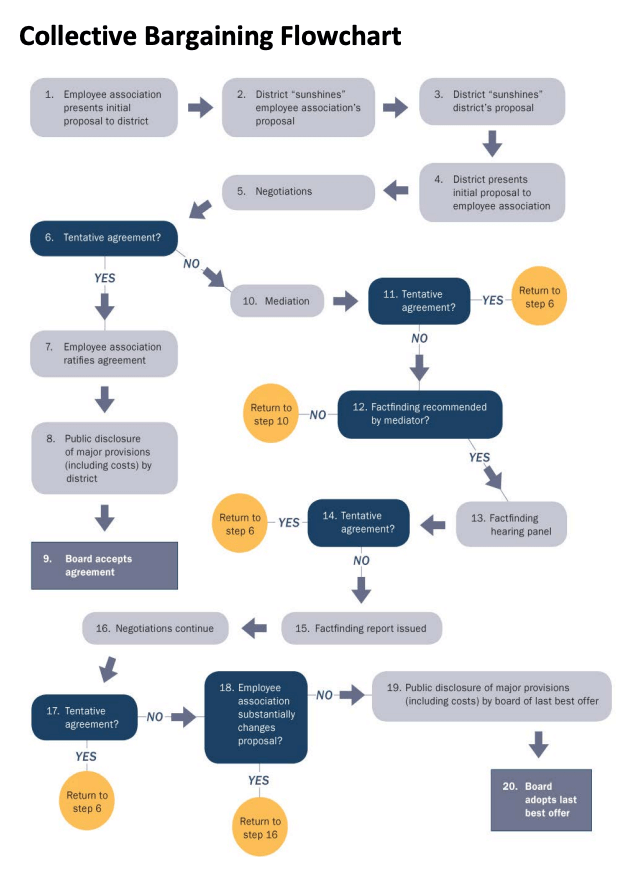

This Collective Bargaining Flowchart from the California School Boards Association (CSBA) displays the many moving pieces in negotiations between the school district and a union.

Communications during the negotiating process

Community members often express frustration when conflict emerges in the collective bargaining process. Parents and stakeholders can feel left in the dark for good reason. They are. Talks between the representatives generally take place privately, with only limited details released to prevent further complicating the task.

Parents can feel left in the dark for good reason. They are.

Frequently, communication with the public will be delayed until a tentative agreement is reached, including an explanation of how the proposed settlement will affect district finances.

On the other hand, public communication can also influence the context of negotiation. School districts are often out-matched in this area because the unions are very good at describing the teachers' perspective in a persuasive way. School boards have to navigate the task of reaching agreements in a way that safeguards long-term relationships and fiscal stability.

What is the role of the School Board?

The role of the board is to set policies related to employment and to represent the interests of constituents. Such policies and actions will include appointing a chief negotiator to represent the district's interests and to consult and advise the negotiating team in closed session.

School board members and district leaders are technically allowed to add their voice during the negotiating process, but they rarely do so. Staying "out of it" is widely considered a best practice in order to avoid mucking up the process or stumbling into conflicts of interest. School board voices are very influential and can undermine the work of the negotiating team.

Staying "out of it" is widely considered a best practice

During the closed session meeting, the school board can communicate certain parameters for negotiations including the amount of money available for negotiations. The board may also check in with the negotiating team throughout the process to ensure that district goals are kept at the forefront during the process. When a tentative agreement is reached, the board should ensure that it is within the scope of the parameters it set forth, that it is financially sound, and that it elevates teaching and learning. Finally, the board will ratify the agreement with a majority vote.

What is the role of the PTA?

The California State PTA has a helpful Guide for Parents and Community Members that can help to include them in the negotiation process. This guide contains thoughtful and valuable questions that PTAs can and should ask of their school board trustees and district negotiators.

Leslie Reckler is a trustee on the West Contra Costa Unified School District Board of Education. She's penned several blogs for Ed100 on popular topics including

School Site Councils,

Open Meeting Laws,

School Accreditation,

How to Hire a Superintendent, and

The Responsibilities of the Central Office. After impasse, mediation and fact finding, her school board just ratified a three year contract with the teachers' union.

Leslie Reckler is a trustee on the West Contra Costa Unified School District Board of Education. She's penned several blogs for Ed100 on popular topics including

School Site Councils,

Open Meeting Laws,

School Accreditation,

How to Hire a Superintendent, and

The Responsibilities of the Central Office. After impasse, mediation and fact finding, her school board just ratified a three year contract with the teachers' union.

Tags on this post

Collective bargaining Teachers StrikeAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Taxes Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

Jeff Camp - Founder February 24, 2026 at 2:48 pm

Jordan April 27, 2023 at 11:11 am

Neil Landers March 13, 2023 at 5:34 pm

Carol Kocivar March 17, 2023 at 10:56 pm

Neil Landers March 19, 2023 at 5:04 pm