Test scores aren’t rising. Whose hot potato is this now?

Shall we look away?

Toward the end of each school year, millions of California students take standardized tests. In 2024, again, scores were about the same as the year before, with huge gaps. It appears that we’re stuck.

That’s terrible news. Who’s supposed to do something about it?

Parents tend to think their kids are on track. But are they?

Students and parents receive scores from these state tests in the summer, at roughly the same time of year as they receive end-of-year report cards from teachers. Often these evaluations deliver conflicting signals. Which should they believe — the cold, impersonal state tests, or the grades from their teachers?

The short answer is that they should believe the state tests.

When awarding grades, teachers use their professional judgment. As every student knows, some teachers tend to be tough graders and others tend to be easy graders. It’s kinda random, but that’s how it works.

Grading standards exist, but no mechanism enforces the meaning of a grade in a report card relative to those standards. Teachers often design assignments and formative assessments themselves, based on what their students are ready to learn — not necessarily based on the expectations that lead toward readiness for college or career. At grading time, teachers consider an important question: what will bring out the best in their students — toughness or encouragement? Suppose a student started the year far behind and made great strides, but not enough to catch up to grade level. What’s the right grade to give?

Why grade inflation is bad

Teachers have few reasons to be tough graders. Nothing compels them to award grades that might make people worried, angry, sad or indignant. No budget limits their freedom to award As and Bs. In most school districts, it’s pretty easy for students to float from one grade level to the next, passing without mastering. As students drift farther and farther from proficiency, their report cards generally don’t convey urgency or alarm.

Years of widespread grade inflation have weakened the evaluative signals built into the report card process, leaving plenty of room for wishful thinking.

When it comes to their own children, parents can be masters of wishful thinking. Surveys have repeatedly demonstrated that parents widely believe that their children will go to college, even in the face of evidence to the contrary. Lulled by less-than-candid parent-teacher conferences, it’s easy for students to think so, too — until they face rigorous college-track courses they aren’t ready for. Most finish high school, but they do so without passing the courses that would qualify them for admission to California’s public four-year colleges.

Average schools… aren’t.

Let’s back up. Why do we have these state tests?

It’s hard to imagine now, but there have been times when improving public education was a top-priority issue in American politics and around the world. Since 2001, federal law has required states to test all public school students each year in grades 3-8 and once more in high school on the subjects of English Language Arts and Mathematics. (Science was added later.) The testing requirement was adopted with nationwide public support. Part of the point of annual testing was to inject a degree of accountability into a system that had demonstrated a tendency to ignore inconvenient students and pretend that all kids were doing fine.

Initially, the annual tests in many states were cheap, lousy, and easy — but they got better over time. The computer-administered, adaptive tests that California uses today were professionally developed using standards shared among a consortium of states. Try them.

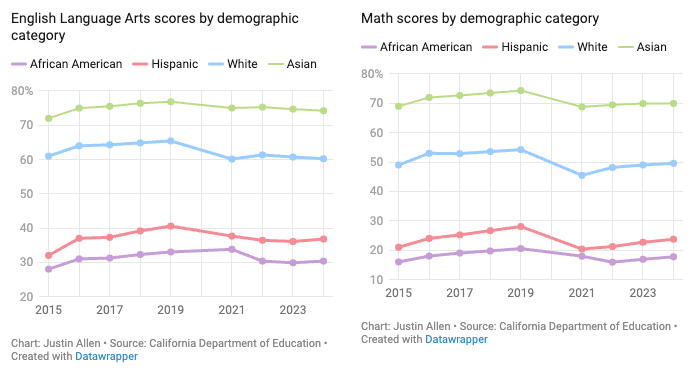

The tests are built on grade-level standards. Some schools tend to do better on these tests and others worse. Schools with more Asian and white kids tend to score higher. Schools with more Black and Latine students tend to score lower. The charts below, from EdSource, show the percentage of California students that scored at or above a cut-point level deemed at least proficient. The lines are basically flat. The patterns of difference, known as achievement gaps, are massive and durable.

Look at them. Don’t look away.

The original purpose of nationwide testing was to drive focus on achievement gaps so that communities where schools have a pattern of “leaving kids behind” would be shocked into action.

Unfortunately, shock proved insufficient to address the underlying issues. Scores on these tests tend to correlate strongly with community conditions, which are hard to change. In schools where families are poorer, kids tend to score worse than those who live more comfortably. Immigration and cultural patterns play a role, too — students who grow up speaking English at home tend to score higher than those who have only learned it at school. Kids do better in households where homework is an expectation, which correlates with consistent parent attention.

The importance of “Each”

Learning is the work of each student. No one can do it for them.

These charts represent patterns, not destiny. When it comes to education, the most powerful four-letter word in the English language is each. The essential work that happens in schools is learning, which has to be done by each student. No one can do it for them.

Effective teachers aren’t just subject-matter experts — they are Jedi masters of motivation. They have to be effective social workers, too — identifying and addressing challenges that get in the way of learning for each student. Each teacher, each day, faces a challenging, deeply human job: help each student choose to direct their attention toward mental work that challenges them, even though it might not feel all that important at the moment.

Now multiply that individual challenge by millions of students. Yeah, this stuff is hard.

Who’s accountable for test results?

Not it! The education system is weak on accountability.

Accountability for results in public education has been a hot potato. Tests consistently show that kids aren’t meeting standards: OK, whom shall we blame? Parents? Teachers? Administrators? Test designers? Textbook writers? Social media companies? Elected officials? Cultural influencers? All of the above? Will blame help?

For a few years, the US Congress tossed the hot potato to school districts, requiring them to take corrective actions in schools with low and/or unequal test scores that failed to improve. Prods to action were a major feature of the No Child Behind Act (NCLB, 2001-2015), which temporarily made the federal Department of Education a central force for accountability and change in public school systems. The federal government became the designated “bad guy” in the system, forcing districts to change. Among other consequences, California law for a few years allowed students to transfer to a higher-performing school if their school was deemed low-performing. Schools with bad results that didn’t improve after four years could be closed or deeply restructured.

After 14 years, Congress grew weary of the “bad guy” role of holding school systems accountable for results. At the end of the Obama administration, NCLB was replaced by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), and the accountability system lost its enforcer. Responsibility for accountability was decentralized to states. In most states, including California, the hot potato was passed again to school districts — presumably to hold themselves accountable.

In effect, the hot potato responsibility — holding school systems accountable for results — landed in the hands of parents, teachers, and local community members.

Under ESSA, states are still required to identify a list of their schools that most need improvement, but there are no consequences that could be described as negative or punitive. The “bad guy” with a big stick was replaced by a system of small carrots: districts where students are failing receive grant funding (ATSI and CSI) and advice. According to a 2024 GAO study, some do improve, but overall test results since the end of NCLB look more like a protracted skid than a steady climb.

California’s system for each student

California’s education finance system, the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), directs resources toward the education of each student, with added resources for schools where student needs tend to be greater. With some federal help, the system also commits resources to serve students with special education needs.

In effect since 2013-14, California’s system emphasizes local power. It entrusts each school district with meaningful power over how to use money. Districts have the authority to hire and train faculty, for example, and to select curricular materials. If kids are behind, the school district has the authority to prioritize its finite resources toward catching them up, including through summer programs or tutoring.

Preventing disasters

California has effective, muscular protocols to head off financial disasters in its public school systems. County and state inspectors (COEs and FCMAT) regularly inspect the books, and train local and regional teams. If all else fails, the state intervenes, rarely and reluctantly.

Protocols for preventing academic disasters, by contrast, have not been as effective. Our system still “leaves kids behind” in large numbers every year, even though we know the patterns through the state’s system of dashboards. If we want a brighter future for each student, the absence of systematic accountability in our education system seems due for a rethink.

Today’s accountability system for California’s locally-controlled schools has several major premises.

- Members of school communities, equipped annually with transparency about results, will notice students that are struggling.

- They will demand better results as part of the annual budget planning process that is solution-oriented.

- Demanding it will make a difference.

But what if nothing changes?

California’s school accountability system

To promote local accountability and improvement, California requires each school district to produce an annual public accountability document (the LCAP) associated with their three year budget, and make sure that people look at it.

Anyone who has looked at these documents will tell you that they are challenging to understand, to put it kindly. It’s easy to suggest that LCAPs should be simpler, but this misses the point. Sure, the documents could always be written more clearly, but school districts are big, complex organizations with a lot going on. LCAPs are authentically complex and detailed because they need to be.

From an accountability perspective, a cricical problem is that few stakeholders are prepared to read and comment on their LCAP knowledgeably. Wishful thinking won’t change this. The hot potato of accountability has been thrown to school community groups like PTAs. School districts and counties should be explicit about what they need from these organizations, and invest in building their capacity to serve that role.

Tags on this post

All Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .

ChrisK1104 November 6, 2024 at 6:07 pm