Taxes, schools, and strikes

Everywhere, all at once

At the end of June, 2025, some of the biggest teacher contracts in California are scheduled to expire roughly at the same time. This synchronization is not an accident — teachers unions and allied labor organizations have worked for years to achieve it as a step toward broader union power in 2028.

Teacher strikes might affect a million California students

For 2025, the participating unions in California aim to coordinate their efforts, align their messages, and demand changes, district by district, possibly under the unifying theme We Can’t Wait. If you think school board meetings have been noisy already, brace yourself. It could get weirder. Talk is in the air of strikes that could interrupt learning for up to a million California students.

|

Expected contract demands |

|

|---|---|

|

Raise teacher pay |

Costs more money. Districts cannot raise funds. |

|

Hire more teachers and staff |

Costs more money because it requires more teachers. Districts cannot raise funds. |

|

“Invest in safe and stable” schools |

Usually this catchphrase is code for subsidizing underenrolled schools, which costs money. Depending who you ask it may include many other demands, including building and upgrading school facilities, and implementing various social justice measures. Again: When it comes to money, districts don’t have the power to raise funds. |

Unions are a vital, powerful element of California's education system, as we explain in Ed100 Lesson 7.5. Teachers unions speak up effectively for interests of their members and for the importance of universal public education. The power of the CTA is one of the biggest reasons why teacher pay has held up better in California than in most other states.

With all that said, the collective demands listed above suffer from some real problems, starting with the reality that they are mathematically incompatible. It's impossible to deliver all of these things at once unless there is a bunch of new money, which there isn’t. Quite the opposite — many of the districts are experiencing declining enrollment and attendance, which reduces revenue.

The second big problem with the demands is that school districts will be powerless to agree to them. School boards have some authority. They can make some tradeoffs about how money is used. But they have almost no power to raise more of it. That power lies with the legislature, or the state’s voters.

As this post will summarize, California’s school funding system is based on formulas in the state constitution. Disrupting school board meetings to demand more money is like kicking an ATM in the hope that cash will pop out.

Worse, if disruptions lead to strikes that cause students to miss school, districts will lose millions or billions in funding. Why? Because in California, unlike other states, funding for school districts is directly based on attendance, not enrollment. Some union leaders argue that the financial damage would be temporary and eventually beneficial, based on an analysis of past strikes. That would be quite a gamble.

Where does money for K-12 schools come from?

Let’s review the basics of how money works in California’s K-12 education system: Which taxes generate money for schools? How is the money used? Who controls it? How does California’s funding compare? What are the options for change?

Learn much more in Ed100 Chapter 8. Click here.

California’s public school system mostly relies on funding from two taxes: state income taxes and local property taxes. For almost all public schools in the state, the mix between these sources is irrelevant. In combination, the funds go to school districts each year using California’s school finance system, the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Under this remarkably rational system, which governs funding for the education of about 96% of public K-12 students in the state, districts receive funds based on the number of students they educate (measured by attendance, not enrollment). Districts (technically LEAs) receive some additional funding to the extent that the students they serve are poor and/or learning English. (See Ed100 Lesson 8.5.)

In addition, districts receive funds from federal programs such as Title I and special education, mostly to reduce class sizes, especially in high-poverty communities. When districts accept federal funds, they typically are required to produce reports about how the money is used. Overall, federal programs accounted for about 6% of K-12 education funding in California in 2024, but this percentage varies enormously by year and by location. For example, during the pandemic Los Angeles Unified relied on federal funding for about 20% of total funding. On an ongoing basis, federal funds are more important for schools in low-income Fresno than in high-income Palo Alto.

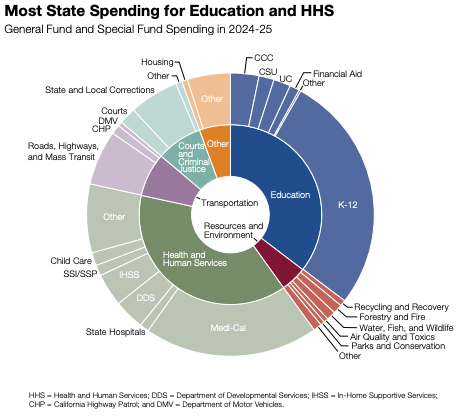

What portion of the money goes to K-12 education?

In California, the amount of state and local funding that goes to public education is determined by rules that voters engraved into the state Constitution long ago. In 1978, voters passed Proposition 13. In doing so, they froze property tax rates and substantially shifted responsibility for funding schools from communities to the state. Ten years after Prop 13 passed, education funding had decayed so badly that voters passed Proposition 98, a constitutional amendment that requires legislators to allocate about 40% of the state General Fund to K-14 education each year.

And that’s basically where we stand today. Every year, the California state budget allocates funding to TK-14 education more or less exactly at the level required by Proposition 98.

The infographic below, from the California Legislative Analyst Office (LAO), helps visualize K-12 state funding in budget context.

The good news about this rules-based approach is that it is predictable. The amount of money that goes to public education isn’t a legislative decision — it’s the output of a constitutionally-protected formula, now stabilized somewhat through formula-driven rainy day funds, which voters added to the state constitution in 2014. (For extra protection, most school districts keep their own rainy-day funds, too.)

The bad news is that the ~40% level set by Proposition 98 is proving consistently too low to give our kids a good-enough education. The worse news is that it might get lower.

Education needs economic effort

As explained in Ed100 Lesson 8.2, money is only good for what it can buy, and California is a famously high-cost state.

A powerful way to evaluate an economy’s commitment to education is to compare K-12 current expenditures as a percentage of the total economy. This percentage is known as its economic effort for education. Relative to other states and nations, California invests low economic effort to fund its schools.

[NEA table F6 / BEA series SAINC1].

What happens when Prop 55 expires?

All tax systems rely on those who can pay. California’s tax systems are particularly dependent on the good fortunes of each year’s top earners. Economic effort is a blended measure, loosely related to the measurement of tax burden.

In 2016 California voters leaned into the strategy of taxing the rich by passing Proposition 55, an important tax for K-12 education paid only by the top ~1.5% of state’s highest-income earners. When high earners enjoy a good year, this measure generates more than $5 billion in tax revenue, but the measure is scheduled to sunset (expire) in 2030.

If the Prop. 55 funds were to disappear, it would be very bad news for California schools and California students.

From crisis to consensus?

The unions’ strike plans, if carried out, will create a crisis that affects families all over the state. Of course, that’s the point.

Could disharmony over local teacher contracts lead to increased public support for state taxes for public education? That’s the gamble the unions are considering. To make a lasting difference, California’s students need their state to shift to a higher level of economic effort for public education. The dream scenario would be for legislators and voters to rally to teachers’ support, preferably on a bi-partisan basis, re-authorizing and expanding Prop. 55 or some other revenue measure.

As the market tumbles and partisanship grows ever louder, is this realistic? Worst-case scenarios are awfully easy to imagine. Strikes generate noise, conflict, anger and blame. Local media and social media will get facts wrong, undermining confidence about whether money is well spent. Rallying teachers to bargain for something beyond their power could lead to cynicism and confusion. Some moneyed interests will attack the consensus for public education directly, using the dispute to argue that subsidies for private and religious schools would be better.

What can school communities do?

As local teacher contracts expire, parent communities can play a helpful role by supporting communication that focuses on the needs of children.

When it comes to money for local schools, the single controllable factor that makes the most difference is attendance. Your teachers are funded by each student who comes to school each day. Roll call actually counts. When a student doesn’t show, no matter the reason, your school’s funding suffers to the tune of at least $60 a day, just counting lost base funding. Ask your district administration and teacher union leaders how they are investing in improved attendance!

There are some other ways to raise additional funds for your school. They aren’t easy. We summarize them in Ed100 lesson 8.9.

If your teachers walk out, or threaten to do so, you might hear calls for “student strikes” as an act of solidarity. This is the opposite of helpful. The best move for students who want to support teachers is to relentlessly show up for them — especially at school.

The purpose of Ed100 is to help school communities understand how the school system works, including the things that do and do not make a difference. Perhaps this post can help your school community prepare to focus on what matters, even if the strikes materialize. I fervently hope they won’t.

Tags on this post

Collective bargaining Funding Unions Effort StrikeAll Tags

A-G requirements Absences Accountability Accreditation Achievement gap Administrators After school Algebra API Arts Assessment At-risk students Attendance Beacon links Bilingual education Bonds Brain Brown Act Budgets Bullying Burbank Business Career Carol Dweck Categorical funds Catholic schools Certification CHAMP Change Character Education Chart Charter schools Civics Class size CMOs Collective bargaining College Common core Community schools Contest Continuous Improvement Cost of education Counselors Creativity Crossword CSBA CTA Dashboard Data Dialogue District boundaries Districts Diversity Drawing DREAM Act Dyslexia EACH Early childhood Economic growth EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Education foundations Effort Election English learners Equity ESSA Ethnic studies Ethnic studies Evaluation rubric Expanded Learning Facilities Fake News Federal Federal policy Funding Gifted Graduation rates Grit Health Help Wanted History Home schools Homeless students Homework Hours of opportunity Humanities Independence Day Indignation Infrastructure Initiatives International Jargon Khan Academy Kindergarten LCAP LCFF Leaderboard Leadership Learning Litigation Lobbyists Local control Local funding Local governance Lottery Magnet schools Map Math Media Mental Health Mindfulness Mindset Myth Myths NAEP National comparisons NCLB Nutrition Pandemic Parcel taxes Parent Engagement Parent Leader Guide Parents peanut butter Pedagogy Pensions personalized Philanthropy PISA Planning Policy Politics population Poverty Preschool Prezi Private schools Prize Project-based learning Prop 13 Prop 98 Property taxes PTA Purpose of education puzzle Quality Race Rating Schools Reading Recruiting teachers Reform Religious education Religious schools Research Retaining teachers Rigor School board School choice School Climate School Closures Science Serrano vs Priest Sex Ed Site Map Sleep Social-emotional learning Song Special ed Spending SPSA Standards Strike STRS Student motivation Student voice Success Suicide Summer Superintendent Suspensions Talent Teacher pay Teacher shortage Teachers Technology Technology in education Template Test scores Tests Time in school Time on task Trump Undocumented Unions Universal education Vaccination Values Vaping Video Volunteering Volunteers Vote Vouchers Winners Year in ReviewSharing is caring!

Password Reset

Search all lesson and blog content here.

Login with Email

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Questions & Comments

To comment or reply, please sign in .