Bye Bye API.

Now how are we going to measure school quality?

This post was contributed by Mary Perry*

How do you know if a school is good or not? For more than a decade, the de-facto answer to that question in California was test scores, and more specifically students’ scores on the state’s standardized tests. The Academic Performance Index (API) each school in the state received was based entirely on those scores. (See Ed100 Lesson 9.7.)

Test scores—all that counted, but not all that mattered.

The API was important. It largely determined which schools were eligible for honors, like being a “Distinguished School,” and which were tagged as low-performing.

It’s not that everyone believed that the API was the only way to measure school quality. The experts knew, for example, that the scores were more reflective of student backgrounds than of what was happening in classrooms. The tests could only shed light on limited skills and knowledge in a limited number of school subjects. But they were available, sanctioned by the state, and simple to understand and communicate. Realtors even used API scores to promote neighborhoods and to justify property values.

Will eight priorities replace one number?

Now it looks like the API will soon be obsolete, or at least a lot less significant. And standardized tests could be just one element in how we grade the quality of a school. [ed. note: this post was published in mid-September of 2014]

Replacing the API could and should be a good thing because we can stop pretending that one number tells us all we need to know about an organization and endeavor as complicated as a school. At the same time, parents and community members -- to say nothing of state officials -- want a reasonable way to compare and understand school performance. Hopefully state policymakers will replace the API with measures of school quality and effectiveness that are more meaningful but still easy to understand.

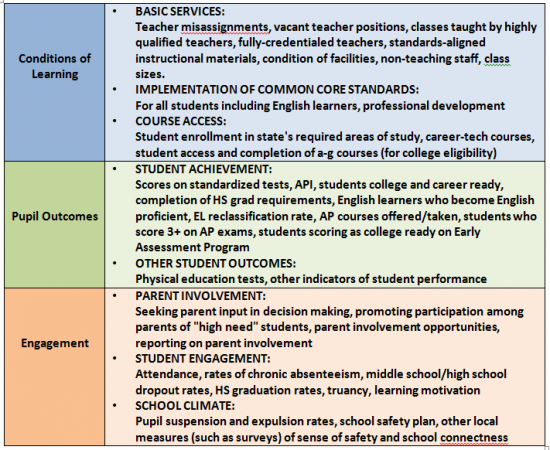

New measurements should be closely tied to California’s new funding and accountability system, which requires school districts to create Local Control Accountability Plans. (See Ed100 Lessons 7.8 and 7.10.) The new state law specifies that schools should be held accountable for eight broad "priorities" and, as the figure below indicates, for a wealth of specific "outcome measures" related to those priorities.

You can see that the API is just one of many measures of student achievement. The one-number score, or some new equivalent, could become part of a much broader report card for school districts and schools.

California's Eight State Priorities and Required Outcome Measures

A new state “rubric” for evaluating schools

Over the next year, the State Board of Education will be designing that report card, which should help districts and communities evaluate schools’ progress and identify areas for improvement. The official label for this work is the LCFF Evaluation Rubric.

Goals of the LCFF Evaluation Rubric:

More information about the rubric and its development is available here.

State leaders want your opinions about this. During the month of September, 2014, the State Board of Education is holding four meetings to gather public input. They will also take comments online from September 18 to 22; details here.

If you plan to participate you might want to spend a bit of time reading and thinking about how school success can and should be measured. A great place to start is Chapter 9 of Ed100.org.

How will performance be reported?

As the state’s Evaluation Rubric work gets underway, I keep wondering whether it will produce a measure of school and district quality that has meaning for the general public and for most of the folks actually working in schools.

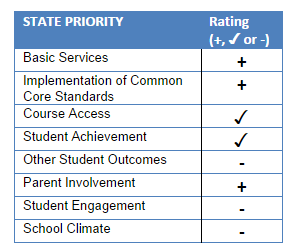

Maybe it will be a bit like those old elementary report cards that give students one of three marks. That seems like a simple enough concept. Or maybe while the state’s evaluation and accountability process takes all eight state priorities into account, a single number measure will still be the most important thing—a bigger, brighter API.

Has our new accountability system already missed the boat?

I can’t help but worry that all of this new accountability work is just tinkering around the edges. Will it really help teachers prepare kids better for their futures?

If you want to join me in thinking more deeply about what kind of state accountability system could have that effect, I invite you to take a look at the report Fixing Our National Accountability System. The report’s author, Marc Tucker, is president of the National Center for Education and the Economy (NCEE). I consistently find him to be a thoughtful and well-informed voice in the discussion about how to improve our schools. At the risk of oversimplifying, his prescription is to create an accountability system that depends a lot less on test scores, instead creating other “very strong incentives for all teachers to work hard and constantly to improve their professional competence or get out of teaching.” His report is interesting reading.

*Mary L. Perry, an independent education consultant in California, helped with the writing and editing of Ed100. Her knowledge of education issues and policies, particularly school finance, was developed during the 18 years she served as deputy director of EdSource, as a local school board member, and as an active parent while her children attended public schools in San Jose.

Join the Discussion

- Should a measure of school quality be easy to communicate, like a grade point average, or should it reflect the many elements that go into an effective school, like a report card?

- What weight would you give each of the state’s eight priorities in an overall “grade” for a school or school district? (e.g. Should student achievement be given a lot of weight and basic services just a little?)

- In what ways might the highest priorities for school district accountability be different in your community than in others you’re familiar with?

Etiquetas de esta publicación

Responsabilidad Índice de desempeño académico Rúbrica de evaluación Plan de responsabilidad de control local LCFF Calificaciones en pruebasTodas las etiquetas

Academia Khan Acoso acreditación Actitud Administradores Agallas Álgebra Ambiente escolar Aprendizaje Aprendizaje Ampliado Aprendizaje basado en proyectos Aprendizaje socioemocional Artes Asistencia Asociación de Maestros de California Asociación de Padres y Maestros Atención plena Ausencias Bonos de obligación Brecha de desempeño Burbank Calidad Calificación de escuelas Calificaciones en pruebas Cambio Canción Carol Dweck Carrera Cerebro Certificación CHAMP Ciencia Cierre de escuelas Civismo Comparaciones nacionales Concurso Consejeros Consejo escolar Control local Costo de educación Creatividad Crecimiento económico Crucigrama CSBA Currículo común cursos de estudios étnicos Datos Después de clases Día de la Independencia Diálogo dislexia Distritos Diversidad Dotado DREAM Act EACH EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Educación bilingue Educación del carácter Educación especial Educación religiosa Educación sexual Educación universal Elección Elección de escuela Enlaces guía Equidad Escasez de maestros Escuelas católicas Escuelas chárter Escuelas comunitarias Escuelas en casa Escuelas Magnet Escuelas privadas Escuelas religiosas Esfuerzo Estándares Estudiantes en riesgo Estudiantes que están aprendiendo inglés estudiantes sin hogar Estudios étnicos Evaluación Evaluación nacional de progreso educativo Éxito Federal Filantropía Financiamiento Financiamiento local Fondos por categorías Fundaciones educativas Ganadores Gastos Gobierno local Gráfica Grupos de presión Guía para padres líderes Historia Horas de oportunidad Huelga Humanidades Impuestos Impuestos a la propiedad Impuestos prediales Índice de desempeño académico Indignación Indocumentado Infraestructura Iniciativas Instalaciones Internacional Investigación Jerga Kindergarten La Ley Brown LCFF Lectura Ley Cada Estudiante Triunfa Ley Que Ningún Niño Se Quede Atrás Liderazgo Límites de distritos Litigación Lotería Maestros mantequilla de cacahuate Mapa Mapa del sitio Marcador Matemáticas Medios de comunicación Mejoramiento Continua Mito Mitos Motivación estudiantil Negociación colectiva Negocio Niñez temprana Noticias falsas Nutrición Organizaciones de gestión para escuelas chárter Padres Pandemia Participación de los padres Pedagogía Pensiones personalizado PISA Plan de responsabilidad de control local Planificación Plantilla Población Pobreza Política Política federal Políticas Premio Prescolar Presupuestos Prezi Proposición 13 Proposición 98 Propósito de la educación Pruebas Reclutamiento de maestros Reforma Requisitos ag Responsabilidad Resumen del año Retención de maestros Rigor rompecabezas Rúbrica de evaluación Salario de maestros Salud Salud mental Se necesita ayuda Serrano vs Priest Sindicatos Sorteo SPSA STRS Sueño Suicidio Superintendente Suspensiones Tablero Talento Tamaño de clases Tareas escolares Tasas de graduación Tecnología Tecnología en la educación Tiempo dedicado a la tarea Tiempo en la escuela Trump Universidad Vacunación Vales Valores Vapeando Verano Vídeo Voluntariado Voluntarios Voto Voz del estudiante¡Compartir es vivir!

Restablecer contraseña

Buscar aquí en el contenido del blog y todas las lecciones.

Iniciar sesión con correo electrónico

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Preguntas y comentarios

Para comentar o responder, por favor inicie sesión .