Cuando los alumnos saben leer, pueden volar

Can a 15 minute screening test help kids read?

Our education system has some basic expectations about reading. Up to about grade two, students learn to read. From grade three onward, they read to learn.

The stakes of this transition are very high. When kids can read, they can fly. Students that aren’t reading by third grade can be left behind very quickly.

When kids can read, they can fly.

At some point, young students who struggle with reading realize that they are behind, often with complicated feelings about it. They may feel pressured, and respond in unhelpful ways. They may want to reject reading as uninteresting or “not their thing.” They may try to avoid reading by acting out. They may hide their difficulties, concealing weak reading skills or dyslexia with clever guessing skills. Or they might just clam up. To get every student flight-ready, teachers and parents have to address underlying issues.

The why of standardized testing

The stakes of literacy are high not just for individual students, but for society as a whole. As we explain in Ed100 Lesson 6.1, the education system is organized around a set of grade-level standards for each area of learning. These standards define our shared expectations about what students should generally know and be able to do at each grade level.

The development of these standards was a triumph of educational leadership at a massive scale — they enable educators to align their work so that students can advance from one grade to the next, one reading level to the next, one educator to the next, and even one school to the next.

Society has an interest in student success

It all works very well — except when it doesn’t. Teachers at each grade level mostly focus on the curriculum for their grade level. When a student falls behind, catching up is really, really hard. Society has an interest in an education system that handles these transitions and notices achievement gaps before they grow. That’s one reason why students are required to participate in some standardized tests.

The big tests

As described in Ed100 Lesson 1.1, two important tests provide information about how well students read.

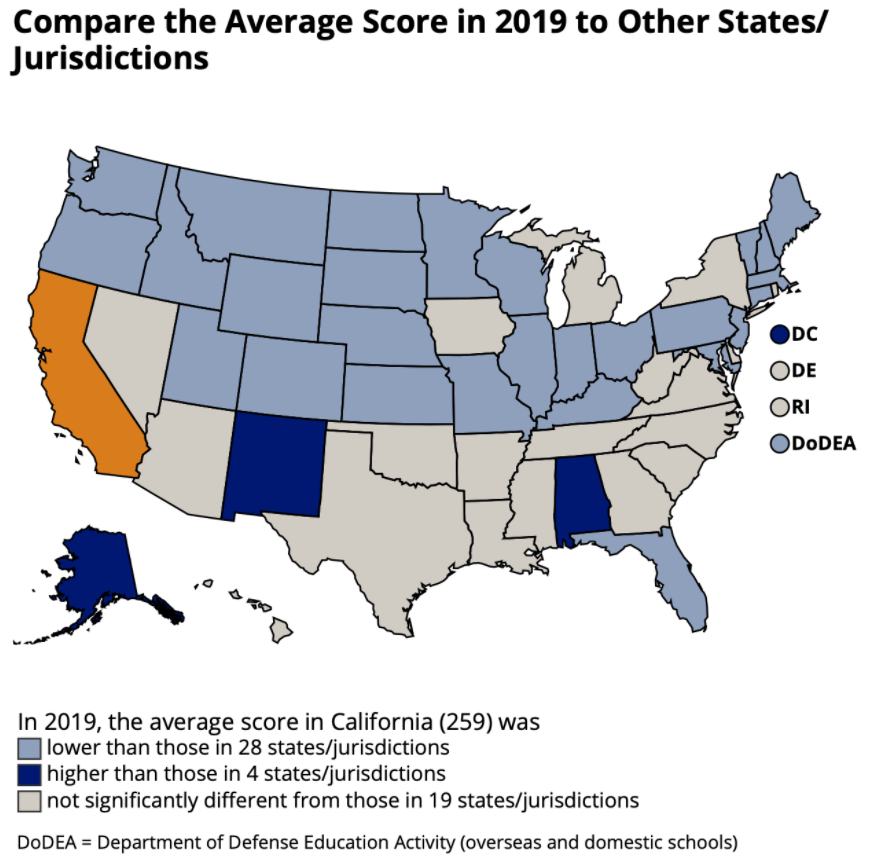

- The Nation's Report Card (NAEP) assesses a statistically meaningful sample of students in every state to allow comparison of acheivement over time. In each state, it tests students in the 4th, 8th, and 12th grade.

- The California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP) assesses students in grades 3-11 annually in California schools.

NAEP and CAASPP measure proficiency differently, but both show that California kids have consistently lagged the national averages in reading proficiency. (Informal school reports suggest that many students fell further behind during the pandemic.)

|

Percentage of students “not proficient” in reading, 2019 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

As measured by NAEP |

As measured by CAASPP |

||

|

4th grade |

67% |

4th grade |

51% |

|

8th grade |

70% |

8th grade |

51% |

Focusing earlier

When a child in third grade can’t read proficiently, it’s not a surprise — or at least it shouldn’t be. Falling behind happens gradually. There’s time to notice it. Learning to read takes time and practice. Helping children get ready to read should begin well before kindergarten, with games and practice to master letters and sounds. At the right age, it’s great fun.

In The Case for Kindergarten Tests, a thought-provoking article for Education Next, Mike Petrelli argues that national and state education systems should focus more effort on early grades, and that learning assessments should begin much earlier.

“Learning assessments should begin much earlier”

“Most kids in this country are starting their education at age three or four, yet we don’t test them until age nine or until the 4th grade,” Petrilli writes. “That’s a long time for policymakers and researchers to be left in the dark about what’s going on and what students may or may not be learning.”

Petrilli is quick to clarify that it would be silly to imagine this as a proposal to inflict old-fashioned bubble tests on kindergarten kids. A decent kindergarten assessment, he says, would be playful, designed on a phone or tablet, and capable of delivering insights quickly. (Hear him explain more on episode #795 of the Education Gadfly podcast.)

Universal screening for risk of dyslexia

Many parents complain that the education system seems designed to wait until children fail rather than identifying student needs early and providing timely support. How do teachers know what kinds of support students need? That’s what universal screening can provide.

“One of the greatest contributing factors to lower achievement scores in reading is the lack of early and accurate identification of students with dyslexia,” according to The California Dyslexia Guidelines.

Nearly all states require universal screening for risk of dyslexia, so that educators can take early steps to support children who might need extra help. California is one of the exceptions.

California’s guidelines recommend that all students be screened for the risk of dyslexia, but don’t presently require it. In 2022, a bill (SB 237 - Portantino) aims to change that. If passed, every school that serves students in kindergarten through second grade would have to screen all pupils for risk of dyslexia and provide support. Because there are many inexpensive or free screening tools available, the authors argue that this would be a low-cost mandate.

Reading advocates, including Decoding Dyslexia CA, list SB 237 as a high priority: “Without universal screening for signs of dyslexia, many students are never identified as being at risk and consequentially, never get the intervention they need to become literate.”

Governor Newsom, who is very public about the challenges he faced as a student with dyslexia, is among the most vocal advocates for addressing dyslexia at scale. The topic sparks a lot of interest and concern, and also a lot of misunderstanding.

There is some resistance to implementing universal risk screening, possibly because it sounds expensive. At least some of the opposition springs from misunderstanding. A full professional assessment for eligibility for special education is a time-consuming process that typically requires a psychologist with specialized training. Risk screening, by contrast, is quick and can be done by a classroom teacher in about 15 minutes, depending on the screening tool used.

Other reading-related legislation

Governor Newsom’s budget proposes substantial funding for expert literacy coaching, one-on-one tutoring with highly skilled reading specialists, access to multilingual libraries, and resources for identification of learning disabilities in the state’s preschool assessment tools. Other legislation, supported by Superintendent of Public Instruction Thurmond and the California Department of Education, proposes additional investments:

|

Some reading-related bills in 2022 |

|

|---|---|

|

AB 2465 (Bonta) |

Would fund home visits to help families reach literacy goals. |

|

SB 952 (Limon) |

Would help existing schools convert to dual language immersion programs. |

|

AB 2498 (Bonta) |

Would support Freedom School programs (Afrocentric literacy programs to help students improve reading.) |

How is your school doing?

- What percent of students are proficient in reading at each grade level? Use Ed Data to find out.

- Does your school use universal screening to identify children at risk of dyslexia? Ask your principal.

- Does your school use a curriculum that incorporates the science of reading? According to EdWeek, The Most Popular Reading Programs Aren’t Backed by Science.

- Are your teachers using updated reading strategies incorporating the latest science about how children learn to read? Ask your principal. If not, what is the school doing to provide teachers with the training they need?

- Does your school provide timely support for struggling readers? Ask parents.

Etiquetas de esta publicación

Niñez temprana Kindergarten Lectura Educación especial Evaluación dislexiaTodas las etiquetas

Academia Khan Acoso acreditación Actitud Administradores Agallas Álgebra Ambiente escolar Aprendizaje Aprendizaje Ampliado Aprendizaje basado en proyectos Aprendizaje socioemocional Artes Asistencia Asociación de Maestros de California Asociación de Padres y Maestros Atención plena Ausencias Bonos de obligación Brecha de desempeño Burbank Calidad Calificación de escuelas Calificaciones en pruebas Cambio Canción Carol Dweck Carrera Cerebro Certificación CHAMP Ciencia Cierre de escuelas Civismo Comparaciones nacionales Concurso Consejeros Consejo escolar Control local Costo de educación Creatividad Crecimiento económico Crucigrama CSBA Currículo común cursos de estudios étnicos Datos Después de clases Día de la Independencia Diálogo dislexia Distritos Diversidad Dotado DREAM Act EACH EdPrezi EdSource EdTech Educación bilingue Educación del carácter Educación especial Educación religiosa Educación sexual Educación universal Elección Elección de escuela Enlaces guía Equidad Escasez de maestros Escuelas católicas Escuelas chárter Escuelas comunitarias Escuelas en casa Escuelas Magnet Escuelas privadas Escuelas religiosas Esfuerzo Estándares Estudiantes en riesgo Estudiantes que están aprendiendo inglés estudiantes sin hogar Estudios étnicos Evaluación Evaluación nacional de progreso educativo Éxito Federal Filantropía Financiamiento Financiamiento local Fondos por categorías Fundaciones educativas Ganadores Gastos Gobierno local Gráfica Grupos de presión Guía para padres líderes Historia Horas de oportunidad Huelga Humanidades Impuestos Impuestos a la propiedad Impuestos prediales Índice de desempeño académico Indignación Indocumentado Infraestructura Iniciativas Instalaciones Internacional Investigación Jerga Kindergarten La Ley Brown LCFF Lectura Ley Cada Estudiante Triunfa Ley Que Ningún Niño Se Quede Atrás Liderazgo Límites de distritos Litigación Lotería Maestros mantequilla de cacahuate Mapa Mapa del sitio Marcador Matemáticas Medios de comunicación Mejoramiento Continua Mito Mitos Motivación estudiantil Negociación colectiva Negocio Niñez temprana Noticias falsas Nutrición Organizaciones de gestión para escuelas chárter Padres Pandemia Participación de los padres Pedagogía Pensiones personalizado PISA Plan de responsabilidad de control local Planificación Plantilla Población Pobreza Política Política federal Políticas Premio Prescolar Presupuestos Prezi Proposición 13 Proposición 98 Propósito de la educación Pruebas Reclutamiento de maestros Reforma Requisitos ag Responsabilidad Resumen del año Retención de maestros Rigor rompecabezas Rúbrica de evaluación Salario de maestros Salud Salud mental Se necesita ayuda Serrano vs Priest Sindicatos Sorteo SPSA STRS Sueño Suicidio Superintendente Suspensiones Tablero Talento Tamaño de clases Tareas escolares Tasas de graduación Tecnología Tecnología en la educación Tiempo dedicado a la tarea Tiempo en la escuela Trump Universidad Vacunación Vales Valores Vapeando Verano Vídeo Voluntariado Voluntarios Voto Voz del estudiante¡Compartir es vivir!

Restablecer contraseña

Buscar aquí en el contenido del blog y todas las lecciones.

Iniciar sesión con correo electrónico

We will send your Login Link to your email

address. Click on the link and you will be

logged into Ed100. No more passwords to

remember!

Preguntas y comentarios

Para comentar o responder, por favor inicie sesión .